[NOTE: Want our YOPD Council to discuss anything in particular in future sessions? We want to hear about it! Let us know what’s top of mind or any questions you’d like to ask panel members by filling out this form.]

During this session, our YOPD Council leaders discuss regaining confidence after losing it in personal, professional, and social settings with the onset of symptoms in young onset Parkinson’s.

You can watch the video below.

To download the audio, click here.

You can read the transcript below. To download the transcript, click here.

Note: This is not a flawless word-for-word transcript, but it is close.

Polly Dawkins (Executive Director, Davis Phinney Foundation):

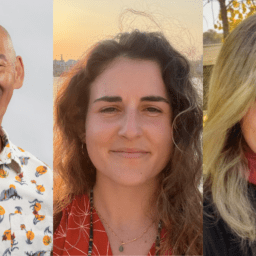

Today I am joined by many of the Young Onset Council here. I’m Polly Dawkins. I am here in Boulder, Colorado at the Davis Phinney Foundation headquarters. Amy, would you introduce yourself and the topic that we’ll be chatting about today and why we’ve chosen this topic?

Amy Montemarano (Davis Phinney Foundation Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader):

Sure. I am Amy. I am in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, beautiful day over here, although the weather’s been really wacky, not as wacky as in California. Today our topic is regaining confidence, which is all about sort of finding ourselves in our different bodies, our different identities, and trying to figure out what to do with them based on what our lives used to be like. And this topic, I think all the topics we talk about here are pretty much all the same topic, and that is sort of, you know, how do we deal with loss and how do we deal with new identities and how do we move forward into a meaningful life and make the best of it? So it’s kind of all the same soup, right? But today we’re mostly talking about people who are diagnosed young onset are mostly in their twenties, thirties, forties, right, fifties. And oftentimes when we are diagnosed at a young age, we are operating in the middle of an otherwise really active life or sometimes we’re sort of at the peak of our competence and confidence in our skills and sometimes professional accomplishments and that’s a peak that’s really hard to sort of fall down from. So that’s what we’re talking about. I think the theme of today is kind of like, can I still do this? You know, can I still do what I used to do? And what I have found is that, you know, I used to have social circles and professional circles that were sort of centered around people with common interests. And a lot of those common interests were you know, activity-based, and now I find myself sort of looking on the outside of that circle and that’s what used to be my native habitat and trying to figure out what to do.

So that’s our topic it’s kind of broad, maybe a little undefined. I’m feeling a little, I feel like I’m losing my confidence right now. Public speaking is one thing that is at the forefront of this. So you might be able to sort of see our topic in action in real time as we go. But for the most part, I think that this confidence that we’re talking about when it comes young onset really manifests itself in three different areas, and one is something that I’m hoping Tom will start us off on. And that is that, you know, the professional sphere, it’s a little bit different talking about, you know, do we keep our jobs, do we disclose all the different employment decisions and aspects of this diagnosis, but it’s another thing to sort of think about all the things that we used to do that we might now back away from, because we’re a little bit nervous about how we’re going to be, so can we still do this?

Can we still go to conferences, make presentations, or even just stand all day, if that’s our job. You know even just going out to happy hour after work with some colleagues, you know, all those things that we took for granted as part of our other lives now sort of, I have to stop and think, can I do this? And the other area is in our social connections. I know that I have a difference between my friends that I used to know before I was diagnosed, my old friends and then my new friends. Sometimes when I go out with my old friends, I feel really self-conscious because they knew me back then. And then the third area is our physical activities and lives. And what we used to be able to do. In this area, I have a thing that I’m afraid of and I call it the really long day, capital R and L.

I’m really scared of sort of planning a day where I don’t, where I won’t be coming home until hours and hours later, because I don’t know how to manage the uncertainty of how I’m going to feel. So you know, a day out fishing or canoeing or kayaking or skiing or traveling… those are things now that I’m hoping that we can talk about regaining our confidence. So that’s the intro. And Tom, did you want to talk about being the professional or just, you know, working, continuing to work in the same way that you used to do but now feeling a little bit uneasy.

Tom Palizzi (Davis Phinney Foundation Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader): I’m feeling uneasy because I was late.

Amy Montemarano:

I want to talk about being late too, because that’s been a thing lately.

Tom Palizzi:

Yeah. I was logged in as part of the audience. I could see you guys, but you couldn’t see me. So anyway yeah, thanks Amy. I was diagnosed 13 and a half years ago or so, and I worked for eight years beyond that point until I just made some decisions that worked that were right for me to leave work and go about my merry way, doing primarily volunteer work since then, but, at any rate there’s a lot of reasons that people leave working. And a lot of it has to do with some of the social pressures that are on you as a person working. Although in my case, I think it was more of a responsibility, a fiscal responsibility as a part owner of the company and executive officer with the corporation. I felt like it was best for me to step down so that decisions that I might make in haste or just without having my hands around because of Parkinson’s or because of my inability to keep up with what was going on with the company and the industry at that time, I just felt it was my duty to step aside so that people could you know, that I wouldn’t cause the company any trouble or problems down the road.

So that was my big reason for leaving, but I don’t feel like, you know, I tell people I miss work. I don’t miss working, but I miss work. Great friends I had there, great friends in the industry, great friends at the company that I was a party to. And that was really hard to step away from. And it’s been harder really to keep in touch with them because they’re still really very busy and I’m not as busy as they are, at least not in the same things, and I tend to be kinda overlooked. They kind of, they left me behind, which is, I get that. I understand that, but that’s a sore point for me. So I think there’s gotta be a balance in there and I don’t know what it is, but I’m happy they’re happy and things are moving along. So, I don’t know if that addresses it enough, Amy.

Amy Montemarano:

I feel like the analogy that I’ve used with my own self is I feel like kind of the weak one in the herd, all of a sudden and you feel really vulnerable to the lion, you know, that’s coming at you. Yeah. Kevin.

Kevin Kwok (Davis Phinney Foundation Board of Directors member and YOPD Council Leader):

Yeah. I think first stepping back for all of us, I think all of us have felt that shock and that sort of being left behind issue. So I think the first thing to put on the table is this is a universal thing that we’ve all felt, it’s not unusual and we’re all going through it and we will continue to cycle in and out of this competency issue because it’s not over yet. Right? Just because it happens once. It doesn’t mean it’s not going to continue to happen. And it’s up to us as I’ve told people, in Parkinson’s, our effort is not to manage the highs, it’s to manage our lows. It’s those troughs that we get into, and how do we get out? But it starts with admitting that we have it right? And we will never be where we once were, but that’s okay once we accept it.

Tom Palizzi:

Sure. I agree with that, Kevin. is, I think in hindsight, I look at it, the older I get the better I was.

Kevin Kwok:

Oh, true. That’s a very wise statement.

Steve Hovey (Davis Phinney Foundation Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader):

You know, Kevin, I mean, Tom, I think I’ve known you for at least five years now, and I can’t believe how similar our story is in regards to work. I left work, I sold my business for very much the same reasons that Tom did. The business was doing great. I just felt that the anxiety that I was feeling, I just was not as effective as I could be. I just became very cautious. And as a small business owner, that was, you know, you need to be cautious, but, you know, you need to take some risks too. And I just felt myself just changing. And then after I sold it, it’s an industry that I was involved with for, you know, for years.

Steve Hovey:

And I, and I had very similar feelings, but it was the right thing to do. And I was able to channel my energy to other areas like, you know, volunteering for the Davis Phinney Foundation and some other things that are very rewarding, but Amy, you know, specifically, you know, talk about something that I was comfortable doing that the Parkinson’s has made me shy away from, you know, I always was very comfortable speaking to other people, making presentations. I was, you know, I was basically in sales my whole life. So, you know, making presentations and preparing and being on was, you know, that was all part of success really. And I found that I wasn’t as good at that as I used to be. And then I started really becoming self- conscious about it, so much so that there was a, I was on a board of a college in Eastern Pennsylvania.

And I was a committee chair, and it got so bad that I couldn’t, when we had full board meetings, I couldn’t even address the group. I had to have somebody from the committee do it for me because I’d get so nervous. I’d forget what I was going to talk about. But what I did was, I then, after I left, after I resigned from that, and I got involved with the Davis Phinney Foundation, I started putting myself in situations where I had to do it. And I’ve become, I’m not saying I’m really good at it, because that would not be the case, but I’m more comfortable doing it. I’ve kind of relearned how to do it, but it has to be the right subject, it has to be something that I’m really comfortable with.

Amy Montemarano:

How about anybody else? Are there other areas that you used to feel really competent in that you’ve kind of fallen off of and trying to regain? Heather.

Heather Kennedy (Davis Phinney Foundation YOPD Council Leader):

Well, just to add to your conversation, we’re in a very performance-based world, so we have body performance, and then we have other kinds of performance, but when your body performance starts to fail, everybody can see it right away. We also, often many of us, not everyone, has cognitive impairment of some sort at some level, whether it’s just simple brain fog or increase in ADD or something like that, you know, that’s why I’m still looking around, that’s my excuse. And I’m sticking to it. That’s why, I have ADD. But I think the thing is with this is we have to sort of kickstart ourselves because it turns out that when we’re uncomfortable and we have to change things that’s when we grow. So we have to think of a whole new way of living and working and being with each other. And that can make people feel insecure and change is hard and we’re kind of inside out, we’re turned inside out. It’s hard to be so vulnerable in our society.

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah. There’s a lot of suffering in feeling embarrassed or feeling ashamed or feeling less than, or feeling incompetent. For me, I just, I don’t know if you guys watch Ted Lasso, but I’ve been taking my cues from him lately. And there’s this one scene in season one of Ted Lasso where he’s playing darts. I don’t know if you guys have seen that.

Kevin Kwok:

Best episode ever.

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah it’s the best. And his thing was exactly the thing that now I use all the time, he said, you know, people underestimate me and I always felt self-conscious and then I realized that you need to be curious, not judgmental. So you know, I said, that’s a really good idea, and let’s just be curious about what it’s like to live with Parkinson’s instead of feeling other things. So you substitute a curiosity in whenever I’m feeling the suffering or sort of the shame or the embarrassment of uncertainty and that sort of helps a lot, you know, just sort of opens your mind up. Yeah. Anxiety is a big problem. It’s tied up in all of this. It’s tied up in a regular life, and it’s also tied up in a life that has sudden change and uncertainty because you’re living with an incurable progressive disease. Yeah. Yeah, Kevin.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. You know, I’m going to go out there and be a little boastful and say that I used to feel like I was the master of the universe in my field.

And my neurologist told me that Parkinson’s is a disease that really plagues Type A personalities that are super achievers. And I think if we look across this panel, everyone on this panel is a super achiever. And to go from this world where you’re on everybody’s Rolodex, everybody wants to call and talk to you to a world where all of a sudden, no one’s calling you, your emails become junk mail from Saks fifth avenue and all these other places. And then you wonder what happened to all those really important emails I use to get it right? And that’s sort of where I’m coming from. You know, in my life, I had sort of figured out how to adjust and pivot to different roles to accommodate my, you know, inability to argue and debate vehemently, you know, at a board meeting, so I felt like I was finding a way to adjust, but last month, in a corporate restructuring, I got laid off, right? And so now all of a sudden, that re pivoting to find my place was turned on its head and I’m going through it again. So I think we just constantly have to pivot to find our new place and it’s going to continue.

Amy Montemarano:

Michelle brings up a good point in the chat, in that it’s helped her, and I think it’s a really good idea to just talk about it, with others, right? Be in a group situation, the more that you are open about it, the less anxiety and nerves that you feel about your new found lack of confidence. Karen. Yeah.

Kevin Kwok:

You’re muted Karen.

Karen Frank:

Hi there. We seem to be talking on the professional end of things. But for myself I quit working as soon as I was diagnosed and I wasn’t really intending to do that, but I was struggling a lot professionally. I had a very high pressure job, which required a high level of multitasking and complex thinking. I worked as a nurse anesthetist in the operating room and I needed great manual dexterity, quick response times, accuracy in the use of my hands. Mainly, thinking. I had a lot of anxiety. I think that was the first symptom that presented itself was difficulty with anxiety. And of course my tremor would get worse when I was anxious and I found myself ill equipped to deal with life-threatening situations rapidly and responsibly. And so initially I took a step back thinking that I would regroup and get medication and be stabilized, medically speaking, and then be able to return to my profession.

But that is not how that happened for me. And in taking that step back, I think that the confidence that I needed to build was how to be relevant in a new capacity, in a new social circle and sort of honing in on things that maybe I had never done before. My job did not involve a lot of public speaking. And I found myself engaging in that new sort of role in volunteer work that I was doing. And being able to sit in front of an audience despite having tremor or various things that I was feeling self-conscious about in light, in the setting of losing myself professionally really helped me to gain confidence with the next thing that I would try. If that makes sense.

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah, so just, you know, feeling, whatever it is that you feel and just doing it right?

Karen Frank:

Yeah. Or knowing that it was okay to, I felt a great weight lifted off my shoulders, it was okay to be anxious and underperforming because I no longer had someone’s life in my hands. When I took a step back from work, I felt that, okay, it’s all right to be having a bad day or a bad hour or a bad week for that matter. It wasn’t, there wasn’t room for error in my work. And so when I was able to take that step back, I, felt at peace in my body, whereas before I felt just battling my body to stay as good, if you will, as I was before this happened to me.

Amy Montemarano:

What about in in your social circles and your friendships and the things that you used to do for fun and still do?

Karen Frank:

That was hard for me because I had a lot of social interactions at work, and I think that I had to rebuild all of that. But quickly found a new community.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. To me, the biggest thing that maybe hurt me was friends through work that I thought were friends stopped calling. And maybe that was the hardest thing of all. And maybe it was because of guilt on their part, or maybe it was, they just didn’t want to kick, you know, here are our continuous stories, but I think the people that I thought were really close to me kind of let you down. But on the flip side, new people emerged that all of a sudden rise to the occasion and you find these new found friends that are always there for you. And so I think that that’s been my silver lining.

Tom Palizzi:

And I totally agree with you on that, Kevin, I experienced much the same thing, but at the same time, I think I’ve always kept the, I took the burden to keep in touch with the folks. I mean, I know I realize some people have struggled dealing with someone who’s been diagnosed with a degenerative disease. And most of them don’t even understand what you’re talking about when you’re telling them you’ve got a degenerative disease, but at any rate, you know, the both socially and professionally in those two worlds I experienced a lot of that same kind of thing. So, you know, some people still ask me, so how have you been feeling lately? Are you getting better?

Heather Kennedy:

I get that a lot? They’re like, oh, I heard there was a cure, I read an article, and I’m like, tell me more. Was it mice or people or when’s it coming my way? I’m all ears.

Steve Hovey:

Or they just won’t talk about it. Right? They just, they don’t even want to go there,

Amy Montemarano:

People are definitely uncomfortable. And don’t always know what the words to say are, so sometimes they don’t say anything. I’m guilty of that myself. People who I know, I, you know, something bad happens to them and sometimes I don’t step up like I should. So again, I just, I try really, really hard to just be curious about why they dropped, you know, why they’re not calling instead of trying to make, instead of giving into the feeling of feeling bad about it. But I also have this I have this sort of tension and I’m sure that you guys do too. And a lot of people do too, which is you get this diagnosis and all of a sudden you want to do everything. Everything becomes really urgent. Your bucket list all of a sudden is right in front of you. Right. And then at the same time all those things on your bucket list, you wonder like, can I even do this? I don’t even know. So then I tend to sort of retreat to my little lair. And especially with COVID, we’ve been inside for two and a half years. I’ve gotten really comfortable inside my house. And sometimes I just don’t want to leave.

Heather Kennedy:

That isolation is so popular that they’ve done studies that prove isolation expedites all the conditions of our disease.

Amy Montemarano:

Yes. I know. Right. Thus the tension. There’s like tension to just go out and do everything but yet you kind of just want to hunker down and hide at the same time.

Heather Kennedy:

How to be together and how to be alone.

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah. Yeah. What do you guys do about that?

Heather Kennedy:

How do we participate? Steve, how do you participate in social activities?

Steve Hovey:

In social activities?

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah, because you moved to a new community too, right?

Steve Hovey:

To a new community? Well, yeah. Yeah. So after I sold the business a couple years later, Nancy and I moved up to Saratoga and we didn’t know anyone. And I really, you know, going back to, you know, like what Tom was saying before I really missed, I missed work. I missed, you know, I kind of just missed being in the game. And I was able to find, it’s called Score. It’s a national organization that does small business coaching. So the great thing is, is I get to work with small businesses and have a lot of fun. And then the meeting’s over and they do all the work and I meet with them again two weeks or a month later. So that really was a wonderful release for me.

And you know when I left and I don’t know if any of you guys felt this way, but I had people like, they go, well, you seem fine. Like, why, you know, why are you selling the business? You seem like, which really made me feel guilty, you know? And I started questioning myself and my wife had to keep reminding me, you did this because you have Parkinson’s and you want to spend the quality time, as much quality time with your family and doing the things you like, which is true. But with score, I went into it, meeting these people for the first time. They didn’t know me, you know it was just a great, that was a great professional change. You know and social.

Heather Kennedy:

Did you get a tattoo like Michael J. Fox, I’m copying him, only he has a turtle I think. Anybody get a tattoo when he got diagnosed?

Amy Montemarano:

I got a tattoo when I got married. Maybe I should get another one now. And Lauren says, curious, not judgemental goes both ways. That’s exactly right. Curious as to why the friends that we used to have may not be so supportive, right?

Heather Kennedy:

I have a lot of ideas about that one.

Steve Hovey:

I just think they’re uncomfortable going there.

Amy Montemarano: Yeah.

Heather Kennedy: Capacity.

Tom Palizzi:

When I was diagnosed, I shared it with everybody. It started inside with my family. And then I shared it with my colleagues at work and ultimately to my employees and the staff. And that really helped because it took away a lot of the, you know, a lot of the wondering why I was walking funny and doing things odd comparatively speaking. And so I think that sort of set the tone and the expectation was there that I wouldn’t be at a hundred percent anymore. So that really helped me a lot. So I always encourage people to do that if you can. I mean, I know that sometimes there’s reasons that people cannot do that in a public or professional environment, but I did the same thing in the social sphere as well. And, you know, everybody knows, they don’t clearly understand, but they all know what’s happening. It just, it takes the pressure off me to act any certain way or react any certain way.

Kevin Kwok:

I don’t know how all of you all, but I have a hard time, even just going out with my friends now, who are, who accept me into a crowded restaurant with lots of background noise, the cacophony of all of that just irritates me, you know?

Heather Kennedy:

Like doorbells? Just kidding just kidding.

Kevin Kwok:

Like doorbells, exactly. But honestly, I can’t hear and listen and talk at the same time anymore. That’s very frustrating for me.

Amy Montemarano:

I’ve switched to day fun instead of night fun. So, and it’s hard, you know, everything’s a shift. And then, when it comes to physical, the long, you know, the dreaded, long day out of the house, I because of, you know, because of COVID, we haven’t, a lot of us, haven’t been really out there doing our kayaking and stuff. Or traveling. And so, yeah, I’m a little nervous. And I spoke, we were speaking about this topic before, and I was talking about how, yeah, you still have to ski and I don’t know if I can ski anymore. And, and Karen has a story about that, I think, right? With your dad.

Karen Frank:

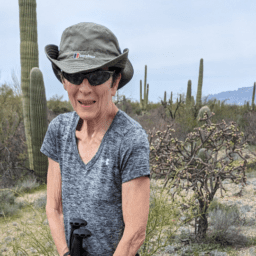

Yeah. Well, my father, watching my father grow up with Parkinson’s disease was it, it gives a little different perspective to my Parkinson’s disease because I’m constantly comparing myself to him. And that’s not always fair to myself either because as you know, one person, one person with Parkinson’s is very different from the next person with Parkinson’s. But one thing I did appreciate about my father is his willingness to continue to do the things he loved and modify them to fit where he was at. You know he, he would ski, for example, you know, maybe eight or 10 years into his diagnosis, but he wouldn’t ski all day long. He wouldn’t ski, you know, 12 runs a day not as many vertical feet, but, you know, if he just sat on top of the mountain and had hot chocolate and did one or two runs in a day, that was a successful day for him.

And I saw a joy in him to be able to spend time with his family, doing what he loved and being able to change the way that he enjoyed skiing. But what, what I experienced Amy that I wanted to share with you, cause I know you would like to ski and are a little nervous about it. But when I ski with the Breckenridge outdoor education center and the national adaptive ability center in Utah, which is in Park City they can pretty much get anybody down the hill. I mean, you can, Parkinson’s or not, visually impaired people can ski, people without limbs can ski. They may do it differently. You know, so I’ve seen people ski with, like for myself, I’m a pretty confident skier, but I would get dystonia and my leg would not, I couldn’t get the ski to turn because my foot was turning inside my boot.

And you know, you need to be able to have translate each little small movement of your muscles in your upper leg, down to the foot to make the turn of the ski. So what I did for an adaptation was very minimal. They carried the chair for me as a backpack. And then when I would get dystonia, I would simply just sit on the mountain in my chair and wait until the dystonia calmed down and then I could resume skiing. So the nice thing about having skiied with them is they would carry the chair for me. And if I just wasn’t feeling up to it in that moment, I’d say, hey, I’m going to sit for a minute. That was my adaptation. You know, I tried skiing without rigors on my hands, which takes about 60% of the work out of the turn. You know, others that needed a little more adaptive support skied with what they called ski legs, which were like a walker with skis, even fully tethering someone where someone would ski behind you and you would be in a mono ski and used just sort of skis on your hands and all you had to do is lean your body, but I’ve seen people with very severe and advanced Parkinson’s skiing. They may not be on their legs, but they’re skiing.

Amy Montemarano:

I want the equivalent of that little chair for like my life.

Karen Frank: You can have it!

Amy Montemarano:

And there’s another organization called peak to peak. Have you guys heard of that? It’s an organization that runs a hike in the Pacific Northwest, every July, it’s free, it’s for people with Parkinson’s and they do all that. It’s all assistive. And they encourage people to sign up and go. And that sounds like a really great program too and it’s really, I think it’s really intense, but at the same time they have people with Parkinson’s at all levels. And I’m thinking about going next July, Next August, I think. Kevin.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. One note on skiing and I don’t want to belabor it, because I think there are people in our audience who don’t ski, and it may be viewed as sort of an elitist sport out there, but there are ways to ski for less than you expect. The Breckenridge adaptive ski program is phenomenal in one sense and it’s very reasonably priced and it’s accessible to just about anyone. The other thing to tell you about is that I’ve been collaborating with some of the ski instructors in Vail and they’ve told me that there’s an Epic adaptive ski pass, which is about a third of the price of the Lift pass. So I just bought mine and I’ve told a few friends and they bought theirs as well. So it’s something you should look for. And then they’re proposing programs where we can have discounted housing, lessons, rentals and everything else as part of it. But the thing that I said that we shouldn’t belabor skiing. It’s really just finding whatever finds you joy, because if it’s not skiing, it could be cycling, it could be dance, it could be karaoke,

Amy Montemarano:

Just hiking, just a day out to hike.

Kevin Kwok:

That’s right. Just getting out there finding what brings you joy. And then just building up as I say, a training program to allow you to do it. The training is half the fun, right? So I’ve got, I go to a little gym around the corner that’s 24/7. And sometimes I call Daveto see if he’ll join me and we’ll set up little obstacle courses, right? We’ll set Bosu balls to stand on and throw balls at each other, try to recite the months of the year backwards. And it’s pretty amazing how much fun you can have with just a few little props. That’s the beauty of where we are is that we can find fun pretty much anywhere. Just challenge our brain a little bit in everything else turns into some occupational therapy drill.

Amy Montemarano:

How do you take that first step to get out of the house? Like, how do you get the initiative to do this stuff?

Kevin Kwok:

Believe me, I’m going to go at three o’clock today and at 2:30, I’m going to be saying, gosh, I’m going to cancel because apathy gets in the way, all the time.

Amy Montemarano:

It’s a big deal. It’s hard to, it’s inertia too, yeah.

Tom Palizzi:

It’s part of the challenge.

Kevin Kwok:

It’s just getting up and really knowing that by doing something, you kind shake off that issue. I mean, you should see me jump rope. I’m horrible now. I, you know, used to jump rope for 15 minutes at a time right? Now, if I get five skips, I’m elated. But what I tell my friends and my girlfriend is like, today, I’ll do three jump skips. Now the next I’ll do five. And then I’ll do 10. And just slowly build these little successes for yourself. You’ll find that if you do that, instead of saying monumentally tomorrow, I’m going to, you know, hike the Camino, right? You can’t just go out and hike the Camino.

Amy Montemarano:

I want to do that too. Shout out to Carol Clupny. The hiking organization is Pass to Pass. Not, Peak to Peak. Thanks Leigh. That was a monumental find for you.

Tom Palizzi:

Yeah, I think what I tried to do, I’m not sure how long ago it was, but a while into having Parkinson’s, after being diagnosed, I started to feel like I had to make a choice of the things that I wanted to do and things that I could do, I kinda analyzed skiing. And I thought maybe I don’t want to separate my shoulder because I was sitting back over here to do this, or do that. I don’t want to get hurt. I don’t want to do whatever. And then I thought to myself, it’s really the challenge isn’t what I can do. It’s what can I talk myself back into doing? Because it’s really easy for us with Parkinson’s to accept the fact that we have Parkinson’s per se and give up on those things. So I make the challenge talking myself back into doing those things, and that’s almost, I don’t want to call it fun, but if I don’t do that, I wouldn’t travel anymore. I would find an easy way to stay home. I’d find an excuse not to go anywhere. If it was hiking, I would find a reason not to hike anymore. My wife and I were out hiking the other day and I forgot my pills. And I was like…

Amy Montemarano:

Oh, right? That’s my fear.

Tom Palizzi:

And I was totally, totally freaked out about it. And I thought, you know, well, the best way to get through a period like that, is just to stay real calm and just keep walking. She goes, do you want me to go get the car? I’m like, honey, what are you going to do when to get the car? You can’t get to where we’re at, let’s just keep going. I’ll make it. And I just stayed calm. And by the time we got there, I was in pretty rough shape, but I survived it. And of course I got in big trouble for forgetting my pills, but that’s neither here nor there. But again, I think the challenge is in talking yourself back into doing those things that you used to do, and you love to do. I hate to give up on things just because of Parkinson’s.

Amy Montemarano:

But you said that was the fun part, talking to yourself back into it. How do you do it? Like, what do you do?

Tom Palizzi:

I have this internal argument with myself. It’s like, you know…

Amy Montemarano:

You like to argue, so that’s fun for you.

Tom Palizzi:

Yeah. Maybe it is. I’m not sure what it is, but again, I think that accepting the challenge is really the fun part is, you know, can I challenge myself to go to New York city and sit through the US open tournament this past couple of weeks, my wife and I went, and it really was a challenge for me to talk myself back into getting on an airplane, flying across the country with a mask on, going to New York city where, you know, who knows what can happen, that kind of stuff, and all the anxiety and all the fears and everything else and physically, you know, what’s going to happen to me when we get there and it’s 11:30 at night and I’m usually long sleep by then. And I’m way OFF my meds. You know, how am I gonna be able to do that? We managed it. We managed it just fine. We wheelchaired out to the car, took the Uber to downtown and got into the hotel just fine. Everything seemed to work out okay. As long as I didn’t let it get the best of me. I was bound and determined to keep myself on the high and dry side of that. So it worked.

Kevin Kwok:

Tom, were you happy you did it?

Tom Palizzi:

Oh yeah. God, what a tournament this year. Holy cow.

Amy Montemarano:

That was an amazing tournament.

Heather Kennedy:

What about ping pong? Does anyone here play ping-pong? That’s good for agility.

Amy Montemarano:

I would love to play ping pong.

Tom Palizzi: Try pickleball.

Heather Kennedy: Anywhere. Anytime.

Amy Montemarano: Pickle ball. Ping Pong.

Steve Hovey:

Yeah. I just wanted to add to what everybody’s been saying. It is really, really important not to stop, just stop doing what you love to do, but you also have to realize that you may not be able to do what you love to do as well as you used to do it. And I, you know, I’ve learned that the hard way on a few things, but I, you know, the only thing that I have quit doing is snowboarding, that I just realized that it’s just a little too slippery for me. But it is important to keep, you know, to just try and keep working at it. And I agree with what everybody’s saying, but yeah, you know, I’ve skied my whole life as an example. And I know now that I can’t go up and do some of the runs that I used to do, it’s just not safe. So 8and that’s been hard for me, you know, it”s just an ego thing. You know, I can’t ride my bike as fast as I used to. I can’t ski what I used to, but you still do it and you love it. You know? So.

Amy Montemarano:

One of the things that I love about skiing, forget about the trappings of it, is just when you’re doing it, you can’t think about anything else. Right? And that’s a wonderful feeling. Everything is just out of your mind, except for just making that next turn. So, when I was talking to somebody about, you know, being afraid of trying it again, they said, well just try something where you get that feeling again, it doesn’t have to be skiing. It can be anything.

Steve Hovey: Like ping pong.

Amy Montemarano:

Like ping pong! Right. Cause you can’t think about anything else. You just have to get the ball.

Heather Kennedy:

Yeah. Right. The nice thing is if we fail we can go Parkinson’s, you know, I mean, I have a million excuses for everything, but that’s my favorite one. And sometimes it even really is true. I think I also wanted to just add too is this integration, like when we don’t integrate what we think we believe about ourselves. Like when we take on too much, when we have these ideas about who we think we are. What if we dropped all those and just tried something new, almost like a child? So this curiosity that you all speak of, everyone here has mentioned, and this awe and, you know, I wonder what’s going to happen next. We just need to keep trying new things. And if we fail, oh, well, we will be better prepared for if we actually fall. Because a lot of these exercises help us with our balance and agility and that’s what we struggle with. It’s kinda like singing karaoke.

Amy Montemarano:

Which we’re going to start in a few minutes.

Heather Kennedy:

Oh, I love it. I take a lot of lessons from my mother, she’s taught me a lot. And she’s someone who’s never complained in her life. Not once that I can think of. And I remember when I was in high school and she had she suffered a third degree burn because she had this whole pot of boiling water fell on her, like, and she ended up in a wheelchair with for several weeks. And when I would come home from school and her leg would be completely covered in big blisters. And she would, she would say to me, Amy, come over here. Isn’t this interesting how the skin heals itself? That was just her way of dealing with the pai and suffering. And so it was, it’s a really great lesson. It’s kind of like, isn’t this interesting how this works instead of, it’s just a mind shift, I think it’s you know, I didn’t know that I was learning that lesson until now. Kevin, yeah.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. I was just going to address Terry’s question on having too many tests in a day and being overwhelmed. I find that, you know, I used to be the kind of person that would do lists and I love checking off those lists, you know, and it was always, almost kinda like, you know, my day. Yeah, there you go with post its. But what I find now is that if I’m in the middle of something and someone throws me a new task, it completely throws me off. And I just don’t have the capacity to say, take on two things at the same time. And so I usually will politely say, can I finish what I’m doing first? And then I’ll come back to the next thing. But the worst thing that I think you can do to Parkinson’s people is show them too many things at once.

Heather Kennedy: Davis taught me that.

Kevin Kwok: Is that right?

Heather Kennedy:

Yeah. I watched him be very careful about what he chooses just a few things and he has a million things going on. So.

Steve Hovey:

You know, a question just came through that I think is really interesting. And it’s, we talked about leaving our jobs because of Parkinson’s, but what if you can’t afford it? So I think that’s a really tough one to address.

Amy Montemarano:

It’s tough. I mean, I’m still in mine for mostly that reason. And we’ve had a couple of webinars about that too. And a lot of it, a lot of the decision-making is sort of acknowledging this really big problem and trying to find ways around it. And there’s lots of resources out there and help if the person who asked that question wants to get in touch. I still have those resources for when we talked about it in the fall and there’s of course no easy answer, but you should know that there are a lot of people out there who are in that same boat and, you know, it’s every day you decide to get up and do your best that day. So I’m happy to talk to you.

Tom Palizzi:

Yeah, there isn’t, and there’s not one, one single answer to help address that, you know, completely, I think it’s really a case by case thing, but you know, companies are, in some ways obligated to at least try to level the playing field for you, with your situation, you know, with Parkinson’s or whatever it is that you’re dealing with to try to find a place for you to still fit into, to keep working, you know, cause it, and, and feel that value of yourself and still get paid for doing what you need to do, but it may not be what you were doing, but there is some obligation, some level of legal obligation for them to at least provide something for you to do while you’re still able to work.

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah. We’ve had some some really good speakers on that in the last year or so.

Kevin Kwok:

I recommend getting a good lawyer to represent you. It made all the difference for me, took the anxiety and the stress away in negotiating my disability. And again, there are people that’s what they do for a living. And if you can find someone who can be your ombudsman and advocate for you and work through the insurance companies or disability, or whatever you have, it’s really great to find someone like that.

Amy Montemarano:

They can also be very expensive though, too, but there are some, there are non-profits, community legal services that do the same in mostly every county, they have a county bar association that you can contact and try to find non-profit attorneys who help you in that same realm.

Heather Kennedy:

And as our needs change, we can get different kinds of professional help outside of our medical care. Most of my help comes from peers right here, like Karen and I have talked about the intersection of sobriety and Parkinson’s. Now many diseases are sort of stigmatized or shamed, and many are not, certainly, there’s nothing shameful about Parkinson’s whatsoever, of course, but people who don’t understand often think I’m drunk. Which, you know, once upon a time, it might’ve also been true. So both things can be true. But now that I know that I’m, you know, I just don’t drink anymore because it doesn’t suit me. It’s easy for me to say, Hey, wait a minute. How could they think I’m drunk? You know, how dare they, when in fact we’re trying to educate people, you know, it’s not like a terrible folk pop per se. Karen, we’ve talked about this a lot, right? This intersection.

Karen Frank:

Yes. I wanted to circle back around to one of the things that Jody mentioned about not being able to quit working. I mean, not everyone has the benefit of having disability insurance or you know, their social security, which is a whole other issue. But I think that sometimes you have to think outside the box about doing things a different way, maybe trying to change sort of the way that you’re working, the way that you’re interacting with your employer about your needs. I don’t know. I’m just gonna take a pause for a second.

Amy Montemarano:

There are also different kinds of employers, some of whom are friendlier to people with Parkinson’s than others. And you know, some of the high pressure private sector corporations are less friendly because of the constituents who they serve. Right? But some academic or government or nonprofit sectors are a little bit friendlier and sometimes you’re able to make a move into those and transfer your skills over. And nothing is, none of it is easy or, you know, going to be handed to any of us. But it’s definitely something that is an option. I reached out to Gaynor. I wanted to get her comment on this topic about confidence, Gaynor, who used to sit on our council. And she said, she moved into advocacy from journalism after her diagnosis. And she doesn’t think that she lost her confidence, just rechanneled it, and the advocacy provides her with the, I guess the distraction, that it’s not about her, right? When you’re out there doing the things that we’re all talking about now with public speaking all day long, you know, feeling exhausted, the fatigue, when you’re there doing it on behalf of other people, sometimes it’s a lot easier and it’s not about yourself, which I thought was a really good point. She also said, remember that no one really thinks about you as much as you think that they do. Which we all need to be reminded of because we’re so self-conscious, but most people don’t really notice us.

Heather Kennedy:

Well when you don’t know if your feet are going to work, it”s easy to be self-conscious. You know we stand up from a table and you do that little Tim Conway’s shuffle thing and we’re kind of like, whoa, you know, people are rushing over maybe to try to catch us if they are paying attention. Most people are just looking at their phones though.

Amy Montemarano:

Exactly. So, yeah, so I mean, a lot of this just internal and stuff for us to work on piece by piece.

Tom Palizzi:

Yeah keep challenging yourself to, to stay in the game. You know, as much as you can work, be social, physical, all that. I mean, one thing we can always control is our ability to challenge ourselves to keep after it. I mean, you shouldn’t do stuff that’s completely off the, well, maybe you shouldn’t, I don’t know. Maybe I should try doing some completely crazy stuff. Anyone want to do it with me?

Amy Montemarano:

I do. Crazy stuff. I love that.

Polly Dawkins:

Hi folks. Tom, that’s a great segue as we close our hour together today on this really important topic, is could everybody go around and just give one piece of advice or one takeaway, one piece of homework that you would like to challenge the audience to think about? Not complicated, but something they could do during the next month to regain their confidence in some area and then come back next month and we’ll start with people giving us some ideas of how they did on that. So, Tom, do you have a, I don’t want to put you on the spot, but do you have a piece of advice that you could share?

Tom Palizzi:

Sure. I’ll challenge everybody to talk yourself into doing that one thing that you’ve wanted to do for a while that you just keep putting it off or finding an excuse not to do.

Amy Montemarano:

You know what, Tom, can you record yourself telling yourself to do that and then share it with all of us and then we can just play it every time we want to do something?

Heather Kennedy:

I love his voice. Yeah.

Amy Montemarano: That’d be awesome.

Steve Hovey:

I would say put together that things to do list, then do it.

Polly Dawkins:

Do one thing in the next month?

Steve Hovey:

No, put together what you need to do and do it. And so actually this is a good challenge for myself. So I’m going to do it also.

Karen Frank:

I think overcoming apathy, one of the things that I find helpful is to put it on the calendar. Like, you know, I’m going to take a bike ride around the neighborhood. I don’t have to ride on a busy trail around cars right now, but I want to learn how to ride a bike. So I want to take my bike to a neighborhood where there are no cars and ride my bike. And I put it on the calendar like Wednesday at two o’clock. If it’s not raining, that’s what I’m going to do.

Polly Dawkins:

Great advice, Heather, Kevin, Amy?

Heather Kennedy:

I recommend extreme flexibility. I’m going to go the other direction from what people are saying. Don’t get me wrong, I have a little bucket list, but I’m going to go with, how do I feel today? What are my specific capacities today in this hour, in this moment? Then we’ll move from there. Now that drives a lot of planners crazy. Not everybody has that luxury. I mean, I have to work too, and I can’t do that at work. So, you know, take everybody’s advice to heart about what your lifestyle is?

Polly Dawkins: Kevin.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah, for me, it’s like finding the thing that you hate the most to do your weaknesses because we tend to focus on our strengths and then turn your weakness into something that you actually really get joy out of trying to improve. I would say that’s one. And the second one is gratitude. Be, just thankful for what you can do.

Steve Hovey: Yeah. Big one.

Tom Palizzi:

There’s a lot of other people who are a way worse off than we are.

Kevin Kwok: That’s right.

Polly Dawkins:

Amy, do you have a takeaway or a piece of homework for folks?

Amy Montemarano:

Yeah I do. I say, find somebody who inspires you and think about a piece of advice that they’ve given. And for me, it’s my mom. A shout out to moms today. Polly’s mom, Abby, I know is out there. My mom’s name is Arlene she’s in Silver Spring. And that whole mindset of when you’re suffering or when you’re feeling bad, just sort of flipping it and bring that Ted Lasso curiosity in and say, isn’t this interesting, where’s this going, can sometimes shake you out of that darkness a little bit and make you look to the future. Thanks mom.

Polly Dawkins:

Well, thank you all. Karen, Amy, Heather, Kevin, Steve, and Tom. Your wisdom, your lived experience is so important as we try to help others, encourage others to get unstuck and move forward. Thank you all. Appreciate you being here and we’ll see you back in a month’s time.

Show Notes

- When you’ve been diagnosed with young onset Parkinson’s and start experiencing symptoms, it’s not uncommon to feel like in areas where you were once thriving, you are now at the back of the herd. It’s natural for this to lead to a lack of self-confidence. While acknowledging that it is difficult, several of our Council members say they move past this feeling by adapting the things they love so that they are still able to do them (for example, Tom adapted his love of biking to his needs) and reminding themselves that their identity and value don’t lay in what they can do, but who they are

- Several panelists said that when they were first diagnosed, some of their best friends stopped reaching out. Again, this was a blow to their self-confidence. However, in time they realized that while they may have lost friends following their diagnosis, they ultimately gained new friends and formed even deeper bonds in the Parkinson’s community

- It’s natural for confidence to wax and wane. Much like everything relating to mental health, it is the continuous practice of healthy habits that will help you regain your confidence when you lose it from time to time

- When symptoms begin to appear, confidence in the workplace can take a nosedive, and for certain jobs, this can leave you with feelings of inadequacy. If your job has a direct, physical impact on another human, such as the healthcare industry, you may also worry about your ability to fulfill the duties of your job in an effective and safe manner. First, it is important to recognize that this is a common concern in the YOPD community, and there is no one right answer. Many people may consider leaving their job and finding a new path. For others, leaving your job may not be an option, and in that case, as Council leader Amy Montemarano explains, it’s wise to take the time to understand your disability rights, as these may help you adapt your role as needed, and remind yourself that it’s okay to have different strengths in the workplace than you used to. Living well with Parkinson’s requires you to live in the moment and adapt

What can you do today?

“Talk yourself into doing that one thing that you’ve wanted to do for a while that you keeping finding an excuse not to do.”

Tom Palizzi

“Put together that to do list of things you want to do and do them.”

Steve Hovey

“To overcome apathy, pick a time for the things that you want to do and write them on your calendar.”

Karen Frank

“Offer yourself some grace and flexibility, and ask yourself how you are feeling in the moment and what realistically you can do today.”

Heather Kennedy

“Find the things you hate to do the most and challenge yourself to find ways to enjoy them.”

Kevin Kwok

“Find somebody who inspires you and think about a piece of advice that they’ve given.”

Amy Montemarano

“When you’re feeling bad or sad for yourself, say to yourself, ‘Well isn’t this interesting… I wonder what’s going on here?’ and ask yourself how you could change it.”

Amy Montemarano

resources and topics discussed

Pass to Pass: An assistive hiking program for People with Parkinson’s

Connect with Your YOPD Council Leaders

YOPD Council: How To Change Careers and Find More Meaning on your Current Path

Working, Ambition, and Parkinson’s

YOPD Council: Work, Money, Meaning, and Parkinson’s

Want to Be notified for future YOPD Councils?

The YOPD Council meets on the third Thursday of every month and every session is recorded and shared for all to access. Register for the YOPD Council series here, after which you will be invited to join live and be personally notified when a new webinar recording is posted. Interested in catching up on past YOPD Council webinar recordings? You can find all recordings on a variety of subjects on our YOPD Council Youtube playlist, and don’t forget to subscribe to our channel to be notified when new Youtube content becomes available.