Written by Kelsey Phinney, BS

In part one of my blog and podcast about facial masking, I explored the “what” of facial masking. I wanted to elaborate on what a masked face actually looks like, how easy it is to take our ability to communicate with our faces for granted and to know more about its impact on social relationships. These questions led me to find Professor Linda Tickle-Degnen to discuss her life’s work in occupational therapy and social psychology and her particular focus researching facial masking.

I learned that facial masking is an important symptom of Parkinson’s to pay attention to because it can limit the ability to communicate emotion.

Impacts of Facial Masking

Facial masking can affect relationships with partners and peers, which in turn, can lead to social isolation. This is paramount, because social interaction has been found to be as important as exercise for health and longevity in older adults. Dr. Tickle-Degnen and I discuss this more in my first podcast on this topic, which you can listen to here.

After my dad listened to my first facial masking podcast, he told me that he spent the rest of the day very conscious of the way he interacted with people and how he expressed himself with his face. It was amazing to talk with him about how much more positive his interactions with people close to him and with random people at the grocery store were when he consciously tried to smile more throughout conversation.

This gave me hope, because it meant that, at least on a good day, a person living with Parkinson’s might have more control over their facial expressions than they think.

It may not be as innate or easy as it is for a person without Parkinson’s, but it is possible to show more expression with some effort.

Improving Facial Expression

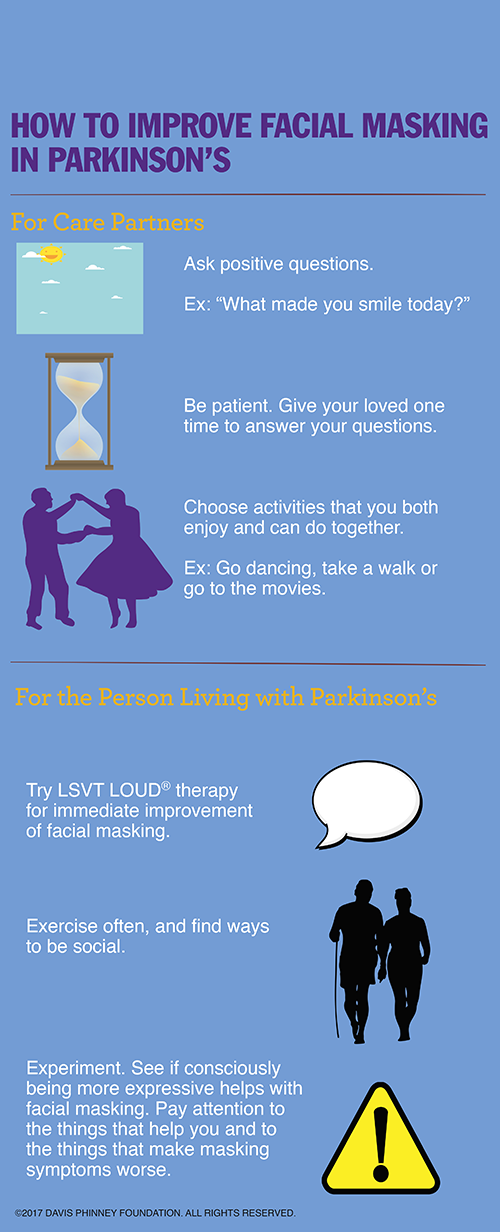

So, what are other ways people can improve facial expression? What can care partners do to create an environment that encourages more non-verbal expression, and what can people living with Parkinson’s do to address their own facial masking?

I learned in the second part of my interview with Professor Tickle-Degnen that one of the easiest and most essential ways of overcoming facial masking is for us — the care partners, children, friends and even health care practitioners — to ask “positive questions.” These questions that elicit positive emotions can be about stories from the past, some recent occurrence that brought a smile or a laugh, or something in the future that the person with Parkinson’s is looking forward to.

Another method that has been shown to improve facial masking, at least in the short-term, is LSVT LOUD® speech therapy. It is possible that because the respiratory system and the face are neurologically connected, working on vocal exercises will in turn, improve facial expressions. Another explanation is that LOUD therapy is usually performed in a group, so the social stimulation may augment the positive effects LOUD exercises have on improving facial masking.

Mimicry and More

The other fascinating topic that I explored with Professor Tickle-Degnen is the controversial research surrounding mimicry and its role in our ability to empathize with other people. Since a person with facial masking is less able to mimic another person’s facial expressions, it is possible that they will be less able to empathize with that person (to read some of the research behind this thought, click here).

Researchers have found that it is more difficult for people living with Parkinson’s to discern negative emotions than positive emotions, which makes sense, given that negative facial expressions are usually more nuanced than positive facial expressions.

I concluded my second podcast with an interview with John Baumann about his experience living with Parkinson’s and facial masking. A Parkinson’s advocate, John told me how masking affects his relationship with his wife and children, as well as shared practical encouragement for those looking to improve their facial masking.

Listen to Kelsey’s Podcast

Everyone’s Parkinson’s experience is unique, just as everyone’s day-to-day living looks different. I’ve learned throughout the process of creating my podcasts on facial masking that relying almost exclusively on the verbal aspect of communication is not something that comes naturally to people, but it is crucial for the success of relationships with people whose facial expressions are masked. I’ve also come to realize that we, care partners and children, can work to practice patience as well as the way we ask questions.

At the same time, with awareness, practice, intention and sometimes outside intervention, facial masking seems to be an effect of Parkinson’s that people can take action to address.

Click to listen to the podcast below

Kelsey Phinney’s dad, Davis Phinney, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s when she was five years old and she has been interested in learning more about the brain and ways to help people living with Parkinson’s ever since. Kelsey graduated from Middlebury College in May of 2016 with a degree in neuroscience and is currently cross country skiing professionally in Sun Valley, Idaho. Learn more about Kelsey at www.kelseyphinney.com.

Kelsey Phinney’s dad, Davis Phinney, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s when she was five years old and she has been interested in learning more about the brain and ways to help people living with Parkinson’s ever since. Kelsey graduated from Middlebury College in May of 2016 with a degree in neuroscience and is currently cross country skiing professionally in Sun Valley, Idaho. Learn more about Kelsey at www.kelseyphinney.com.

I’m interested in the source for the study Linda was referencing regarding the neurophysiology of the face and the relationship to respiration. I’d love to read more about this. Kelsey, this information about the impact of facial masking & things people can do to better communicate has been very helpful to me. I will help to educate our community about this.

Libby, the article Dr. Tickle-Degnen referenced is titled, “The neuropsychology of facial expressions: A review of neurological and psychological mechanism for producing facial expressions.” The article was published in Psychological Bulletin and can be purchased for additional reading at here. Hope this helps!

Your second blog is very interesting as it relates to “care partners”. We realistically cannot perceive the difficulties confronting people living with Parkinson’s who are trying to control their facial muscle movements. It takes strengthening a whole new set of neural pathways (namely, Hebbian learning). This takes a lot of brain energy so that fatigue and distractions can lead the increasingly dysfunctional automatic pathways to supervene. Result: facial masking.

Persons with Parkinson’s will inevitably decide how, or if, they wish to devote energy to avoid facial masking, or to their long-term safety and independence needs. Your blog speaker (John Baumann) put that very well.

Thanks for your comments, Richard. Facial masking is definitely a challenge. But as John Baumann puts it in the podcast, “You can impact your facial expression… I think you can affect it more than you think… but you’ve got to make a decision to do it.” Check out the LSVT Loud® speech therapy program to learn more about how it can improve facial masking.

Thank you for the exploration of this important topic. I’m in my fifth year with a Parkinson’s diagnosis, and I find that facial masking is the scariest part of the whole symptom suite. Thanks for inspiring me to start working on it specifically. I’ll let you know how it goes.

Please keep up the great work!

Mark, we’d love to hear about the your journey! We hope the more attention you pay towards your expression, you’ll begin to see positive results. Stick with it and keep us posted!