Brian Grant had a long and successful 12-year career in basketball. In 2008, at age 36, Brian was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Davis Phinney was an Olympic Bronze medalist and Tour de France stage winner who claimed the most victories of any cyclist in American history. In 2000, at age 40, Davis was diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Since being diagnosed, both athletes have made it their mission to do all they can to thrive with Parkinson’s and inspire others to do the same.

In this genuine, inspiring, and relatable conversation, Brian and Davis talk about their experiences as athletes receiving a Parkinson’s diagnosis, their difficulties in accepting the physical and mental challenges that have occurred with the progression of their Parkinson’s, and how and why they are passionate about living well with Parkinson’s each and every day.

To download the audio, click here.

You can read the transcript below. To download the transcript, click here.

Note: This isn’t a perfect transcript, but it’s close.

Soania Mathur, MD (Family Physician, Davis Phinney Foundation Board of Directors Member, YOPD Women’s Council Leader and Co-Founder of PD Avengers):

Hello everyone. I’m Dr. Soania Mathur I’m family physician and someone who’s been living with Parkinson’s disease for over 22 years. I also have the privilege of being a member of the Davis Phinney Foundation, Board of Directors and the Brian Grant Foundation Medical Advisory Council. And I have the distinct pleasure of sitting down with two of my favorite people, Davis Phinney and Mr. Brian Grant. You know, there are a few blessings that come with this life experience. And one that I recognized for sure is the friendships that you develop with people that you wouldn’t normally cross paths with. And I’m really grateful for those opportunities. I think if it wasn’t for that, we would not likely be sitting here today. So hello to you both and big hugs.

Brian Grant (NBA Athlete, Founder of the Brian Grant Foundation): Always a pleasure to see you Soania.

Soania Mathur:

Thank you. You know, as I look around the screen, too bad it wasn’t around the room, we couldn’t be there in person, but I think the three of us kind of are prime example of that this disease really knows no boundaries when it comes to age or race, ethnicity, gender, or nationality. And we all sort of represent that heterogeneity or a spectrum of disease where everyone with PD really is unique in terms of their symptoms, course of disease, prognosis, and treatment response. And I think people listening would be very interested in hearing your stories, your sort of diagnosis stories. We all have them. So maybe Davis, could you start us off and tell us when and how your diagnosis came about?

Davis Phinney (Olympic Cyclist, Founder of the Davis Phinney Foundation):

Yeah, I mean, I was diagnosed around 20 years ago and so I’ve been living with this disease for close to 30 because I can trace my symptoms back even that much farther, but my diagnosis was difficult to be made because at the time there just was not young athletic type of people like myself who were really being diagnosed with PD. And so everyone looked at me and they said, well, I mean, he sort of presents like he has Parkinson’s, but that couldn’t be possible. And so it took me a while and I went through the whole spectrum of medical professions. Basically seeking an answer before, before someone just gave some Sinemet and said, why don’t you try this and see how, how it works? And it was like, Oh yeah, relief. And then subsequently we ended up moving to Italy of all places, because I felt like I was under such a microscope of being looked at as a guy with a disease and everyone in Boulder or everyone seemingly was kind of giving me odd bits of advice. And so I just felt like I really wanted to escape and find a place where no one knew me or knew of my backstory and just accepted me and that worked out because, because as I said, we moved to Italy of all places. And so that was where I was able to come to terms with my diagnosis.

Soania Mathur:

Right. Someone actually sent in a question ahead of time and they were wondering if you noticed, like, did you notice your symptoms first when it came to it affecting your cycling? Was that how you sort of first noticed that there were some physical changes that were occurring? Or how did you first notice?

Davis Phinney:

Well, now that I understand the symptoms more, I was more struggling with my left foot, which was cramping continuously when I would go out for a run. And so it was less of a problem cycling, but it was definitely a problem coming on when I would exercise. And then eventually my little finger started to twitch. And now it’s sort of what inspired me to stop looking for a physical therapist type solution and look at neurological solutions.

Soania Mathur:

Right. I mean, it’s interesting, it’s unfortunate, but the story you tell about people not knowing what was going on and thinking you were too young for it to be Parkinson’s disease, and not entering their headspace is actually, unfortunately, the same story that a lot of people that are more recently diagnosed with young onset Parkinson’s disease face as well. Not that much has changed, unfortunately, over the years. Brian, how was that with you when you were diagnosed?

Brian Grant:

Let me back up a few years prior to being diagnosed, when I was traded to LA from Miami in 2004, 2005. I noticed that my game was really starting to decline, but in this league of a professional athlete, you just see that with people. So I didn’t think anything of it until I actually got to Phoenix. When I arrived in Phoenix, I started to notice that I couldn’t jump off my left leg as easily as I used to be able to. It was very awkward. And I actually saw a neurologist while I was there because I had a small skin twitch in my skin. I mean, it wasn’t even noticeable. And I asked what it was. And I was told that, you know, after having a long career that I’d had and being banged up as much as I was, you’re going to have a little things like that happen.

So I didn’t think anything of it. I thought that, you know, it was nothing to worry about. I’d spoken to a player, I used to play against who was retired, who was talking to me about depression for athletes, because, you know, we’re retiring very young from something that we’ve done our whole lives. And so when I came, when I was diagnosed with depression, after going through six months of denying myself that there’s no way I could have depression. You know, I thought that depression was for weak minded individuals, but I was so wrong. I was so wrong. After I came out of that, I had the finger twitch just like Davis and moved back to Portland and then I was diagnosed with young onset Parkinson’s at OHSU by doctor and at the time I was going through so many other personal things that it was, I made a joke about the scale in his office because I had put on a little bit of weight.

And so we both laughed. And then I went home and two weeks later it hit me that I had this disease. And I got scared because I didn’t know if that meant that I needed to sit my kids down and tell them, you know, dad might not be here the next year, or was it some, you know, was there a surgery or anything, but I want to say this, if it wasn’t for people like Davis, Michael J. Fox and Muhammad Ali, then I would have been lost. I mean, I probably would have the hid with the disease rather than stepping out with the trying to help. So, you know, Davis, you were helping people like me, you know, for a while and I’m really grateful for that. And I know there are a lot of people out there that are grateful for you and Michael and Mohammed. And to answer, I don’t know if you asked the question, but it was other Parkinson’s patients that I got to meet that really also changed my life because I got it from their perspective. And I started to learn about medications and the effects that it was having on different people. And, you know, neurologists are good at their jobs, but they’re not very good at answering those kind of hard questions that you can ask somebody in your group. So, yeah.

Soania Mathur:

Yeah. I mean, I think we can all identify with, you talked about Davis and Muhammad Ali and Michael J. Fox that we all have to kind of stand on the shoulders of the giants that came before us. And it really, I think the impact that they have and have had on our entire Parkinson’s community and now you as well, Brian, is really, it’s really underrepresented. I don’t think we recognize it as much as we should do. Davis, did you find the same thing that you learned from your peers more so than the neurologist you may have saw at the time in terms of the practical side of things?

Davis Phinney:

Well, that’s an interesting question because I definitely was learning from my peers, but I was also governed as an athlete and as a long-time athlete I felt like I was smarter than this disease and I could figure out some work arounds with it, but that proved ultimately, not correct. And so I became somewhat of my own worst enemy in that I was actually not doing myself any favors by not taking my meds correctly. And in feeling like, well, I can beat this thing, and I was just so stubborn about it. Finally, I found my neurologist, Helen Bronte Stewart in Stanford, and she was just the right person with the right vibe who came from an athletic background. She was a ballerina. And, so that sort of got me straight and thinking about doing things more correctly.

Soania Mathur:

Right. I mean, that kind of comes stems to acceptance. And I would imagine that coming from such a physically demanding profession where you both are so in tune with your body and what you can do, how did you, I guess, how did you come to that point of acceptance that with this disease, some things really with your body may be beyond your control. Was it a difficult process or concept to come to terms with? Davis?

Davis Phinney:

Well, you’re assuming that I’m totally accepting of this disease. And I would say that even now 20 years, post-diagnosis, I still ebb and flow with acceptance but that doesn’t mean that I can’t focus on living well and doing my best, making my best effort to enjoy my life. But yeah, the acceptance is, I think something that even as I say now, I still struggle with completely accepting this disease.

Soania Mathur:

Oh, I mean, I agree. I think that acceptance can be really hard to reach sometimes. I mean, I found it took me probably nearly a decade to actually accept my diagnosis, not intellectually. Intellectually I knew I had Parkinson’s, but emotionally. But once you’ve reached that type of acceptance, you can at least start to move beyond your diagnosis to sort of take control of certain variables to be able to optimize your life. How long did it take you Brian to reach that level of acceptance, maybe not full, and when did you decide to begin to sort of prioritize living well with this disease?

Brian Grant:

Let’s see, I was diagnosed, once I was diagnosed and I knew what it was, I knew what was going on with my body. I had turned down so many opportunities to try out for broadcasting and things like that. Things I always saw myself doing after the, you know, the ball stop bouncing for me. So I kind of hid with it. It didn’t take me long to accept it enough to come out with it, you know, I thought that that would take longer, but like I said, I saw the people who were on the forefront of Parkinson’s and they gave me courage to step out and let the world know that I had Parkinson’s. As far as totally accepting it, I’m with Davis on that. I mean, it’s still an ongoing process, especially with the playoffs on right now. You know, I sit back, and I watch NBA games, that’s probably why I don’t watch them that much anymore, but I have to watch the playoffs because they’re so good.

But when I see that, it kind of kicks me back a little bit because, you know, I’m reliving in my mind when I used to be in what I thought was control of my body, and now I’ve lost a lot of that. And it really messes with the accepting process, especially emotionally. I think physically Parkinson’s takes that away each and every year, something new comes up. But I’ve kind of, I think I’ve kind of accepted that that’s going to happen in my life, but the emotional side for me is tough.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah. I can totally relate to you Brian on that front because I mean, I had that same role after I had finished cycling. I was a commentator for bike racing and that fairly quickly went away right away. And, so even now, I mean in my head, I’ll watch by bike races, and I’ll make this comment or that comment, but then when I speak it out loud, it comes up sounding like mush. And so there’s, you know, you just recognize that there’s no way you can, you can work in the way that you used to or that I can anyway. But that being said, what’s so wonderful about having our conversation here today. We’ve got three great spokespeople and ambassadors for Parkinson’s. And that’s a really powerful thing. I think that for us to be able to reach out to people and not be so self-conscious, that we would not do this, I think is wonderful. So thank you both.

Soania Mathur: Thank you, Davis.

Brian Grant: Thank you, Davis.

Soania Mathur:

And you touched on one thing. I mean, we don’t have control over the diagnosis. We don’t have control over how it affects our lives. I mean, I see a medical show, or I see my husband leaving for work and I get still that little ping of, oh gosh, I wish I was doing medicine again as well. But one uniting goal that I think that defines both of your foundations is your mission to improve quality of life for people living with the challenges that this disease presents on a daily basis. Because truthfully until that cure comes about it’s all about quality of life and what those quality-of-life goals are will vary from person to person. For some, it may be running a marathon. For others, it may be just getting to the end of the driveway so that they can check the mail. I mean, both are very important for the person who’s defining them. So what are your quality-of-life goals, I wonder?

Brian Grant:

To try to live as normal life as I possibly can. I want to be there for my kids. I want to see my daughters down the aisle and my goal is to be able to walk them down the aisle versus someone having to wheelchair me down the aisle to give them away. I know that Davis, this may happen to you sometimes too. Sometimes my meds work so well and I go a little extra longer without any symptoms. And I start to trick myself into thinking that I don’t have it. It happened more often in the beginning than it does now, but it still does. And that’s kind of a road that I need to stop going down because it’s kinda like putting your hand over a lighter and not thinking you’re going to get burnt and you get burnt. But my biggest concern are my kids and being able to walk my daughters down the aisle, being able to be there to watch them grow and being a grandpa and just everything that any normal person would want.

Soania Mathur:

Those are great goals.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah, that’s a great answer. I feel like Brian, what you described was my experience when I was pre-DBS and I was on Sinemet where I would get that place where your Sinemet does, where everything it’s just like, ah yeah, this is it. I don’t actually have this disease, that’s just all BS. And then of course, you know, within a few minutes of overdoing my dose or not taking it on time, I start swimming around and struggling. But I feel like to answer your question, Soania, for me, living well is about enjoying as many moments in any given day that are not dominated by Parkinson’s. And so I think that that comes with a certain level of mindfulness, where I’m focuses on positive outcome and just enjoying whatever I’m doing. And, and when it comes to my symptoms, I tend to tackle them one at a time and say, you know, okay, my sleeping has gone to pot, what can I do to help my sleep? And then I’ll go about finding ways to improve that symptom and then I’ll move on to something else. But, I mean, this disease, as we all know is no picnic. And so it’s just a matter of defining whatever makes you happy in the day. And hopefully that happiness also translates to you making a habit of doing something that’s beneficial for your health and beneficial for your Parkinson’s.

Soania Mathur:

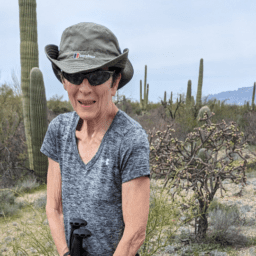

Those are wise words, very wise words. Actually, since you brought up health. During our conversation last week, we were chatting about exercise, and it was so interesting to me anyway, how you both approach it differently. It’s sort of very much in line with the way you must’ve trained in your professional athletic careers having the differences that they do. So what have some of the challenges been for you and sort of incorporating the way you used to train and what you need to do for your Parkinson’s disease? Brian?

Brian Grant:

Discipline. For me, it’s been discipline. I have to learn a new, I’ve been learning a new, but I have to learn a new level of discipline that says, Brian, you’re not the athlete you used to be. You know, you can’t train like you used to train. In basketball, it’s a lot of stop and go quick spurts. And that takes a certain kind of training to have that anaerobic shape, to be able to get through an 82-game season. And now with Parkinson’s, I can’t train that way. And it’s like I was telling you, Davis, I’ll go like a month of just a little bit at a time. But then my mind starts to tell me, what are we doing? You’re not going to lose weight, or you’re not going to feel better if you don’t ratchet it up, let’s go, get it going.

And I do, and boom, I pull something, or I strain something, or it does the opposite, it ends up making my tremor that much worse or heavier rigidity. So for me, it’s just being able to find or be disciplined to do, to know that, first of all, I’m not a professional athlete. I’m a retired professional athlete. I used to play basketball, you know, and now I’m in the game of life going up against Parkinson’s and that’s a whole different foe and a whole different approach. And, you know, Davis, you gave me some good advice in our last conversation and I’m just trying to apply that to everyday living, just to do a little bit each and every day. I don’t have to get it all back in one week, even though my mind is like, I think I can, even if I could, it’s not going to come back the way it used to because I’ll be 50 next year. And I don’t have all those, you know, hormones in my body that allow me to shred up. So the discipline aspect of it for me has been tough, and ongoing and it’s a work in progress.

Davis Phinney:

Well, that’s great to hear Brian, that you’re trying to get that consistency because for me unlike Brian, my whole thing was consistent training day in, day out, year in, year out. And so I’ve been able to translate that to more of a Parkinson’s friendly activity level, but it’s that daily thing that I, for the most part look forward to, which sustains me, and that’s been really helpful. But what’s funny is people, even today, people who know me, know of my disease and whatnot, they’ll come up and they go, dude, you look so fit. You must be ready to race. And I’m like, yeah, not even remotely close. But I guess I should take it as a compliment.

Soania Mathur:

Yes, you should. And then, a couple of viewers also asked questions specifically about exercising, sort of self-proclaimed couch potatoes that really haven’t started exercising and they hear all about, you know, exercise being the one thing that we can do as patients to help ourselves in terms of our symptoms and the way we feel on a daily basis and what we can accomplish. So what would both of you advise someone who’s just been diagnosed, maybe a little bit older, has never really taken exercise to be part of their daily life. How should they get started? Or what would your words of advice be? Davis, do you want to start?

Davis Phinney:

Yeah, I would say it’s just about creating a habit, finding something that you enjoy it enough that you’ll do it on a daily basis and start there. And with the philosophy, something is always better than nothing. And so, it doesn’t have to be one thing. It could be five different things, but of those things, I feel like what’s important is that you get outside if possible and walk, if that’s all that you can do, and go from there. And maybe you get up to bike riding, maybe you don’t. But then there’s also a myriad of classes available for our community. Which, if you’re the kind of person who needs to hold yourself accountable because of a friend who’s nagging, come on, man, go to this dance class, then there’s that available. And one thing that’s really changed with this pandemic is the availability of classes online. And so you don’t have to have like necessarily a pedaling for Parkinson’s group active in your own hometown. You can just dial one up on the internet and it’s sort of like Peloton, but it’s Peloton for Parkinson’s.

Soania Mathur:

You know, that’s great. And you’re absolutely right. I mean, the pandemic has had a lot of challenges, some great things have come out of it. If one can say anything great came out of the pandemic. But one of those is the online availability for people. There’s not much of an excuse when, and I know it’s on both of your foundation sites, that there’s some great exercise opportunities available. So Brian, what would your advice be?

Brian Grant:

Same as Davis. Find something you like to do because ultimately what we’re talking about is people continuing to keep it moving. So many people that I meet with this disease are sitting back waiting for that cure, thinking that, you know, the cure is just right around the corner, and it may be, but in the meantime you gotta get up and move. You know, I’ve been guilty of that. I’m a world-class athlete, was a world-class class athlete. And I sometimes give into depression and get lazy, you know. During the pandemic, you know, that wasn’t my best moment as far as exercising and things like that, I kind of gave into the dreariness of the pandemic, you know, being with my kids, dealing with depression. So it happens to everybody. It doesn’t matter if you’re a world-class athlete or not, but the thing we’re trying to say is, do something. It’s better to do something that you like, something that’ll keep bringing you back.

But even if you do some things you don’t like, just keep moving. Because once for me, when I quit moving, I tell you what it was like planting a garden, all these new weeds just started sprouting up, like man, when did that happen? You know, I’m having a lot more trouble swallowing, and you know, oh my God, I’m constipated. Just things went haywire. And so once I got back into a little rhythm and started moving, it didn’t take everything away, but I felt much better, and I could deal with those things. So just movement.

Davis Phinney:

And what Brian talks about with apathy is so common with our community. People just letting themselves go because they just don’t have the will to struggle with the disease. But Brian, you said that very well about people needing to just get moving, because if you don’t move, then you stop, and that sort of inertia becomes harder and harder to find.

Soania Mathur:

Yeah, absolutely. Two things came to mind as you were both speaking. One is the depression issue that Brian, you mentioned a couple of times, and that is something that I want the listeners to know is that that’s something that’s very common in our community. You know, even before the motor symptoms start, you can get depression as you were describing before. And sometimes people might call themselves depressed, but it’s mainly apathy. And that sometimes you can sort of, you know, work on through accountability and, you know, positive thoughts and optimism, but sometimes people get real depression and that really requires medical intervention. So people should never feel hesitant to seek medical attention, to see if their depression is really something that needs to be taken care of with either medication or counseling or a combination of both.

The other thing that you mentioned, Brian, which I think is really important is that you can’t be a passive bystander in this disease, you have to take an active role. Like you were saying, you can’t just wait around for the cure. It’s something that you have to do actively. And when we look at the Parkinson’s landscape, I mean, ending Parkinson’s is obviously the end game, but we really need to approach that end goal in two parallel tracks. One is that much needed research into better therapies and a cure, which is also important, but in many ways, as equally important is optimizing quality of life, while we wait for those treatments and both of your foundations are focused mostly on that track, living well with Parkinson’s disease. So what motivated each of you to take on that work? What made you sort of decide to start a foundation to do that? Davis, I guess you first, because you know, it’s a little bit, you’ve been around a little bit longer with your foundation.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah. Well, I mean, I sound like a broken record with people being passed, but what happened with me was fairly early on when I was diagnosed, I would run into people with Parkinson’s and they would just tell me that, yeah, they were just waiting for someone to cure this disease and I recognized that by them waiting, that was too passive of a response. And so, and with passivity comes more decline. And, and so I felt like if maybe the best thing I could do was use my voice, not in the curative sense of finding an overall cure, but in the curative sense of helping people just feel better right now. And so that’s where our foundation started.

Soania Mathur: Brian?

Brian Grant:

I was pretty lost one once I was diagnosed, but I knew I wanted to do something. So we ended up having our first gala which was a huge success. It brought a lot of people out, but we just didn’t have, I didn’t have the vision to give to my executive director and say, okay, this is what we want to do. I knew I wanted to help people. We went through several different ideas, a website that supposed to do all this great stuff and, you know, kind of looking to see what everybody else was doing, but things really came together. I think when I met Katrina Call, I met you and Aaron at our events and I kind of just relate to Katrina. I just want to help people. She said, well, what are you best at? I said, what do you mean?

She goes, well, I mean, exercise, nutrition, you’re a world-class athlete this, you know, let’s get it together. And so that was kind of how I, we were already thinking nutrition and exercise prior to Katrina getting there. But once she, once she got there, she picked it up and really moved it forward, you know, getting advisory boards put together. You know, just getting all the information that we were gonna need to be able to create the foundation that we have now. And I think with people like you, Davis, who were at the forefront of things, you know, you kind of made it easier for us to kind of slide into that niche with you to be able to help people in the same way that you were doing it. Yeah.

Davis Phinney:

Well, and I feel like one of the best things that we can do is get other, learned people together and dispense information, even beyond exercise and beyond diet, and go into the whole medication management, etcetera, etcetera, because there’s other ways with which you can find joy in your life. And so the more that we can dispense a broad variety of information, the better off our community will be.

Soania Mathur:

Yeah. That’s great. I mean, Davis, you’re talking about sort of future directions. Is there anything in particular that you find exciting about where the Foundation, Davis Phinney Foundation is heading, any projects in particular you’re excited about?

Davis Phinney:

Well, one thing again, to go back to this pandemic is that we’ve always done large in-person events called Victory Summits®, which people have gotten quite a bit of inspiration and information from but having to take all those online was not necessarily a bad thing, because we were able to do more than just reach the people who would come to our room. And so, in that way, that’s been a good thing, but then looking forward to the future, I feel like the more that we can expand our message out to the community and certainly there’s underserved parts of our community. And so we’re trying a new program that helps local places, whether it’s Portland which is Brian Grant’s stomping ground or Boulder, which is my stomping ground or Tulsa, Oklahoma or wherever, we’re looking at creating initiatives for small communities to come together and help them with that. I’m sorry. I can’t speak that well.

Soania Mathur:

No, no, Davis, you’re doing great. And you’re absolutely right. I mean I’ve been at the Victory Summits and they’re amazing places, the mood and the optimism and the inspiration that people get from attending those are really phenomenal and to be able to offer that same sort of content to a larger audience through online offerings is really tremendous and can help a lot of people that you wouldn’t normally reach. So that’s great. And Brian, what about you? Is there anything you’re excited about that the Foundation is planning down the road?

Brian Grant:

Yeah. we have an exercise conference coming up a week from Saturday, which is going to be huge for us. You know, when we first started in exercise, we thought, okay, let’s start bootcamps locally at the YMCA. And we had some really good connections, but we weren’t able to get the information out there enough to fill those classes. And so Katrina came up with, rather than trying to build these classes, let’s build a curriculum that we can put trainers through and so we’re basically training the trainer. And when I say trainers, I’m not just talking about, you know, just a physical lifting trainer, but an MMA coach, boxing, whoever uses exercise, which is everybody and their training methods can become certified, Parkinson’s certified. And through that certificate, you can basically say if I come to your MMA gym, I’m like, I have Parkinson’s, that’s all right, I’m Parkinson’s certified.

So that was one of the biggest, one of the bigger things that we did that I think has been very well received within the Parkinson’s community. We’re doing like Davis said through zoom and the internet, thanks to the pandemic, we’ve put together mental health webinars. We’ve kids, parents with Parkinson’s, which your daughter participated in and my two sons. So, I mean, there’s a lot of things that we have in the works coming up. But I think the most important thing is what’s happening here right now, because you know, there’s two people from two organizations that kind of do similar things who are actually communicating and were saying, I like what you do, you like what we do, let’s get together and put the information out there together, because not only in the Parkinson’s community, but anything cancer, any disease, any organization that’s created to help in that fight. A lot of times, it’s hard to get people together. It is because you’re dealing with donations and dollars for your programs and things like that. But I think this is a great start, what we’re doing right now. And I think I hope to see more of it with other organizations definitely in what you’re doing Davis.

Yeah. Sometimes I ramble on, sorry, folks. I mean I’m here with Davis Phinney, come on.

Davis Phinney:

No, you’re good Brian. You sound so much better than me. I’m sitting here thinking I should just shut up and let Brian speak.

Soania Mathur:

No, both your voices are so important. And something that you know is we’ve talked about this when it comes to the PD Avengers, is that whole collaboration, that together we can put an end to Parkinson’s that we can get it done together because working in silos and duplication of efforts, it’s not only a waste of resources, but it’s most importantly a waste of time. And that’s something that none of us here on the call today, or in our audience, or the wider community, we don’t have that time to waste. So that’s really great advice for other organizations, Brian. Did you want to add to that at all Davis, about collaboration between different organizations and how that can work?

Davis Phinney:

Well, I mean, I feel like Brian and I have such a good communication, already, that this is a natural fit for me to do something of value to the community and what that is, I think we’ll probably leave it to our executive director Polly Dawkins in my case, and Katrina in yours, Brian. But that collaboration is so important because it allows for us to not view ourselves as competing for resources. Because I think for both of us, we feel like if we can help the Parkinson’s community most directly to feel better and function better, then that’s what we’re going to do. And so yeah, collaboration is key.

Soania Mathur:

It is. And I’m sorry to say, but I hope I’m going to put out of business fairly quickly and that there’s no need to have a Davis Phinney Foundation for Parkinson’s at least, or a Brian Grant Foundation that we can all sort of celebrate over a drink when that comes to be. And Polly and Katrina are such remarkable people. I think they’ll definitely try and help make that happen for sure.

Davis Phinney:

Soania, you started the PD Avengers. So you’re familiar with having a Foundation yourself. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

Soania Mathur:

Sure, Davis. The PD Avengers is basically a group of global advocates who are unifying the voices in the Parkinson’s community to basically end Parkinson’s disease. So just a little bit of a mission, but we hope to work with other organizations like yours and Brian’s to help people not to work in silos so that we can have a united voice, that we can add urgency to the cause of Parkinson’s disease. And we’re working on three pillars. One is advocacy, making policy changes. The other is equity and care because we believe that globally, people deserve equity and care, including basic access to medications and third is the patient voice in research, because really the patient voice is important and research from the ideas that are generated, to actually planning the clinical trials to disseminating the information afterwards.

So those three key areas we hope to unite the globe or the world Parkinson’s community to work together. We’re not a charity. We don’t raise any funds. We just amplify your messages at the Davis Phinney Foundation, the Brian Grant Foundation to basically make this an urgent need, because it is. We’re dealing with a disease that still was identified 200 years ago. And our medication that’s the gold standard is over 50 years old, we have to do something. We have to become a loud and uncomfortable voice in the ears of people that can make a difference. So it’s all of a collaboration. Thank you for asking.

One thing I wanted to add, Brian, you mentioned Arin, that’s my husband, and I know you both know him, but he’s been telling me lately that I’m sort of losing my work-life balance, but for me it’s kind of like, well, how do you take a break from a disease that’s constantly challenging you and reminding you of the community that you’re sort of devoted to helping. So how do you both maintain that balance in your lives? I mean, family I’m sure is a big factor for both of you.

Brian Grant:

Yeah, family. I have an executive director who is so driven, so driven that, you know, she, I don’t want to say makes it easy for me, but she kind of lays it all out and I take a look and say yeah, we should do this and bring it to the board. And we move on to the next issues, you know. But you know, when I know we have things coming up, you know, I set my schedule. I make sure that I check my kids’ schedule, make sure they don’t have anything coming up, but really just communicating, being able to communicate with Katrina, who can communicate with my second oldest son, Elijah. And they make things a lot easier than me trying to do it because I’ll forget something, I’ll forget your name and it’s not because I’m trying to do it, but my memory is just not there like it used to be.

Davis Phinney:

I hear that. I hear that, Brian. I mean, I would say basically the same thing is my work-life balance is fine because I have such a great, amazing team around me that starts actually with my wife Connie and then Polly Dawkins who along with Katrina is the hardest working and most effective woman in Parkinson’s. And then this whole team that we have assembled out here, that’s the Foundation, which is like Mel, and these guys, and others who are so dedicated and work so hard for our cause. And so, that just allows me to basically be the visionary of the Foundation and I don’t need to sit in on every meeting So, yeah.

Soania Mathur:

Yeah. It’s sort of the way most people should live with Parkinson’s, right? You need a team of support people to sort of help you live your best life. And you’ve got that in many more ways, which is great. So, my last question for you both is, you’re both professional athletes. You’re both familiar with those pre-game talks either by your coach or psyching yourself up or your teammates. So, what would you say to someone who like you is sort of facing this ultimate challenge, trying to live well with Parkinson’s disease? Whoever would like to start first.

Davis Phinney:

I would just say, you know, you’ve got this challenge ahead. It’s going to be years and years. And so, the best thing that you can do is to become proactive on your own behalf and start looking at developing the team, as you said Soania, and start thinking of ways with which you can engage yourself physically and emotionally and mentally. And if you can do those things, then you will be living long and well with Parkinson’s. I mean, I think that the important part is that it’s possible to live well with this disease and that’s the takeaway that should be the takeaway.

Soania Mathur:

Thank you so much. Brian?

Brian Grant:

I’m going to give Davis the drop the mic sign. Bam, that was a good one. That was a great one. No, everything that Davis said. I mean, that’s basically it in a nutshell. But I do want to, I’m thinking back to the second gala that we had, and there was a lawyer who came out with a couple buddies to attend, and we were eating dinner and he told me his father had Parkinson’s and he gave me this description of what Parkinson’s is. He said it’s like climbing a mountain. You know, you’re going to find it hard and rough. And then you hit a little plateau, you know, your meds and everything will be working, you’ll feel good. But then you got to start climbing that mountain again until the next plateau comes. And then up and then the next plateau, and I know I probably messed the story up, but it made me think, you know, with this disease, you gotta have a team.

Like you said, Davis, you gotta put together a team. How many people? I don’t know. But for me, it starts with my kids, they’re my caregivers, my neurologist, my chiropractor, because a lot of times my body gets locked up and bent out of shape, and then having friends that you can call on, like, you too. I mean, I’ve called you several times, you know, when something was going on Soania, and I’m glad to have Davis’s information, so I have another friend to lean on. But you gotta lean on those people when you truly need it. And more so than just leaning on them, you gotta be there and be available for them too. It can’t be a one-way street where you’re giving everything and you’re not receiving. So, I don’t know if that’s what you, you know, what we’re looking at. That’s what I got.

Davis Phinney: That’s great, Brian.

Brian Grant:

I got confused myself there.

Davis Phinney:

I think what we’re both ultimately talking about is having gratitude and expressing gratitude to those who are in our circle who help us.

Soania Mathur:

Absolutely. And speaking of gratitude, thank you both so much for taking the time to share your thoughts, experiences, and advice with our Parkinson’s community. I mean, your vision for the future is what we all desire, a world with no Parkinson’s disease, but until then, a world where we can all thrive, not just survive with the challenges that this disease brings. And don’t, as Davis always says, forget to celebrate your daily victories.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah, we need to go arms up.

Soania Mathur: Thank you so much.

takeaways from brian and davis

Living well with Parkinson’s means choosing to control what you can and letting go of what you can’t.

“I still ebb and flow with acceptance, but that doesn’t mean that I can’t focus on living well and doing my best, making my best effort to enjoy my life.”

-Davis Phinney

Depression is a common non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s due to physiological changes in your brain. Brian says he spent six months trying to convince himself that he didn’t have depression.

“I thought that depression was for weak-minded individuals, but I was so wrong. I was so wrong.”

-Brian Grant

Regular exercise has been shown to be one of the best things you can do to live well with and possible slow the progression of Parkinson’s. But exercising consistently is hard, especially if you haven’t exercised a day in your life. The best advice we’ve heard from people with Parkinson’s and professionals is that the key to moving your body consistently is finding an activity (or five!) that bring you joy.

“When I quit moving, it was like planting a garden. All these new weeds just starting sprouting up. And once I got back into a rhythm and started moving, it didn’t take [all my symptoms] away, but I felt much better and could deal with those things.”

-Brian Grant

Additional resources

Grit: A Conversation with Angela Duckworth on being “gritty” and achieving your goals

Depression, Anxiety, and Apathy in Parkinson’s

want more videos like this?

Subscribe to our Youtube Channel to see the latest videos and get notified every time we post a new video.