Recently, someone in our community shared a DBS story with us. We want to share it with you because they learned some important lessons that may be helpful to you someday. We hope you (or someone you love) never have to go through something like this, but in case you do, we want you to have the benefit of learning from the author’s experience. It’s not an easy read; however, they are very hopeful about the future and grateful to be feeling healthy again.

Written by Anonymous

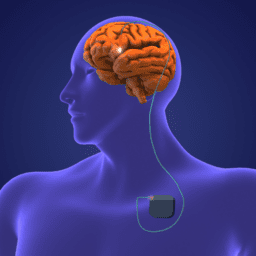

Any person living with Parkinson’s who has undergone Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) surgery knows the relief it brings. Relief in the form of easier movement, reduction of tremor and in many cases, less reliance on medicines.

Occasionally the unit may be powered down for re-programming. And in some cases, it can power down unexpectedly. (This happened once to my person with Parkinson’s in the Frankfurt airport!) Usually, the person with Parkinson’s becomes symptomatic and very uncomfortable. Fortunately, relief is usually on the way in the form of a reboot and restart.

My person with Parkinson’s had his DBS implanted ten years ago. It changed his life. And it was a Godsend considering that Parkinson’s had already taken so much from him—his ability to work, the reliability of his cognition and speaking abilities, waning executive function, coordination, balance, etc.

Because we had so much experience with the vast array of Parkinson’s symptoms and almost twenty years of living with the disease, we thought we understood the true magnitude of the condition. We were wrong.

Here’s the story of our journey through the wilderness of being literally switched off and of the lessons learned.

My husband discovered an infection in the area around the pulse generator in early June. The infection caused swelling that pushed the battery pack forward, which made it more visible. There was also a red bloom on the surface of his skin with a line indicating that the infection was moving. Because this is a potentially life-threatening situation, the decision was made to remove the DBS device immediately.

I was out of town at the time visiting family, but I was assured that the surgery was mild enough that other family and friends could care for him in my place knowing that I’d be back for the recovery. Not rushing home to be there for it (or stalling the procedure a few days) was mistake number one.

Removing the DBS Device

The surgery was performed under general anesthesia. Two incisions were made across the upper right side of the chest and behind the right ear to remove the extension wires. It lasted for almost two hours due to rigorous disinfecting, the difficulty of pulling the wires that were embedded under the skin and the now ten-year-old connection points that had become difficult to uncouple.

The surgeon tried to keep our expectations reasonable: It will be uncomfortable, but his medications will help. The surgeon made it sound like he’d be just fine. Uncomfortable. But. Fine.

Or maybe that’s what we wanted to hear.

He’ll be fine, right?

Unfortunately, surgeons don’t deal with infections of this type very often. (Infection rates vary widely – from 2-10% of all cases.) And the complications of removing a device can vary greatly depending upon how long the person has had the device in place.

In addition, because surgeons are first and foremost concerned with the success of surgery, they will most likely undersell the consequences of removing the device. Their concern is with the outcome of the operation, and in this case, it’s the neurologist who will work closely with the patient on medications. What can be underestimated, however, is how much your quality of life will be impacted by not having the device. And in our case, it was worse than anyone could have ever predicted.

After the Surgery

Over the years, my person with Parkinson’s had become accustomed to taking a very low dose of extended-release Rytary, rather than immediate-release Sinemet. Since it was hard to predict how he would feel without his device, we had no idea going into surgery what his medication needs would be after the surgery, and neither did the medical staff.

Enter mistake number two – not having a better plan regarding his medications. Looking back it seems we should have introduced more medication into his system before surgery, and certainly, right after it. As it ended up, more than five hours passed post-surgery before any medications were administered due to the rigors of the surgery, the focus on the surgical procedure and his recovery from anesthesia.

We took it for granted that his body would adapt quickly to the medications when he did take them; however, the abrupt removal of the device seemed to shock my person with Parkinson’s system severely and rendered him almost ‘locked in’ or paralyzed.

The shock came from so many angles: powering down a device that had been on for 10 years, the duration of the infection (the IPG device had been installed 20 months earlier, meaning the infection had been brewing for a long time) and the surgery and general anesthesia, which are particularly difficult for people with Parkinson’s. The biggest shock of all, however, was that his body and brain were unable to process and utilize Sinemet.

If this sounds dire, it was.

A one-night hospital stay turned into three with minimal improvement in his function and escalating frustration and fear. All normal digestive processes seemed to stop, and nausea was a big problem. Sleep was impossible due to the intensity of the rigidity in his muscles. And to add insult to injury, because my person with Parkinson’s couldn’t move and therefore couldn’t push the button to call a nurse, a family member or friend had to be with him 24/7 to make sure he received the care he needed.

I can’t stress enough how challenging the medication situation was. To put it simply, we faced two major problems:

1) His brain cells didn’t know what to do with the medicine.

2) Hospital staff members are trained to dispense medication through a lengthy process and only as directed by a doctor (Meaning, patients rarely have input as to how much they need and when they need it. Plus, it can take an hour to get them.)

This brings me to our third and biggest mistake: we placed more value in being at a hospital closer to home than being at the one that was closest to our movement disorder specialist. By the time I tried to get my husband transferred to a different hospital, it was deemed medically unnecessary. (In other words, it wasn’t covered by insurance.)

On the fourth day, we took an arduous detour that required three hours of driving, two wheelchairs and several large men to help him in and out of our vehicle so that we could see our specialist before finally heading home. Exhausted.

The detour was worth it because our doctor immediately insisted that we increase his medicine by more than double or triple from what he was taking at the hospital. To do that, she prescribed anti-nausea medicine, so he had a better chance of keeping the medication down. She also stayed in close contact for the first month to help us through the process of finding the right medicine regime.

The Recovery

While we were at the specialist, three friends convened at our apartment. They borrowed a walker, bed rails and a transport wheelchair from the local Elks club. They removed small rugs and tripping hazards. And they made runs to the pharmacy and grocery store. Fortunately, our apartment was already partially prepared with grab bars and minimal furniture.

However, even with all of the help and support we received, it was a month before my person with Parkinson’s could be left at home unattended. Someone had to be with him at all times to ensure he took his medications on time and to help him with critical daily activities. (To be precise, he couldn’t toilet himself, he couldn’t get in and out of a chair and he couldn’t feed himself.)

Part of his recovery involved at-home rehab that included regular care from a nurse and a physical therapist. Also, his sister stayed with us for six weeks and managed the night shift while I managed the day. He had to be physically moved in bed day and night because he was more or less like a turtle on his back: stuck. We arranged pillows and sheets very carefully and strategically to help move him because he couldn’t move once he lay down. (We didn’t understand why, but this immobility persisted for most of the time he was off DBS.)

One of the best tips we heard from a friend who is a rehab physical therapist was to get a condom catheter at night because he couldn’t move, and we couldn’t move him fast enough to get to a bedside commode. Strangely, this tip was not suggested by the hospital staff or at discharge. (Adult diapers provided some assistance in the day but are not adequate at night.)

During his recovery, his core muscles continued to be mostly shut down, even as he transitioned quickly from using a walker to walking unassisted. He had to be pulled and rocked out of a chair. He continued to be a fall risk. His hands were like bear paws, and his feet were clumsy. His shoulder flexibility was minimal. And simple daily tasks we had long taken for granted like dressing himself, bathing, toileting, teeth brushing and eating continued to require assistance.

His daily in-home physical therapy at 9:30 am gave us structure and helped him develop strategies to move when frozen, to be more independent and to coordinate and activate the muscles that weren’t cooperating. Due to the heat (it was summer) and his inability to sleep in, we walked every day early in the morning and late at night for at first 10 minutes, then 20 minutes and then for as long as an hour.

The medications started to kick in after about seven to 10 days, nausea subsided and digestion started to become regular. His appetite took a long time to return, and he continued to lose weight. Even though the medications worked better, they only provided relief for about one hour of every three. And at night, he felt trapped and unable to roll over or get up on his own. Occasionally he froze in bed, which made him extremely anxious. We installed a baby monitor so that we could hear him when he was alone in the bedroom.

I bought a blender, straws and drinking vessels with lids. We learned very quickly that proteins needed to be avoided altogether or at least very carefully timed. And anything that wasn’t taken in by straw required assistance. So great was the level of care he received that it was almost as if we had a newborn in the house (albeit a very large one!).

Life with DBS… Again

Finally, after ten very long weeks of being without his DBS implant, my person with Parkinson’s had a new pulse generator and connecting wires implanted. This time we chose the hospital closest to our movement disorder specialist who, to our relief, appeared at his bedside in the recovery room. This hospital was more extensive and featured a dedicated ‘neuro’ floor with nurses who had been trained to understand the needs of people with Parkinson’s. For example, they offered him his Parkinson’s meds, but they let him decide when to take them or if the timing should be tweaked. We asked the nurses and staff not to disturb him at night for a solid six-hour block, and they complied.

The experience made us wonder how many other hospitals have this level of training and service for those who have Parkinson’s? It makes all the difference in the world.

It wasn’t an easy surgery, but within 48 hours, the troubles of the summer started to recede. Hopefulness returned along with an ease of movement and the promise of better days ahead. I predict we’ll be tweaking his medications and programming for a while, but he’ll soon be back to normal activity levels. I can’t even tell you how much joy that brings both of us.

Parkinson’s disease is all about management. It’s about predicting best and worst-case scenarios. It’s about being prepared. And more than anything, it requires a strong advocate and a superior support team. We knew that, and yet we still made assumptions that went against his best interests. Mistakes were made. Perhaps we could have anticipated the worst and prepared ourselves mentally and emotionally for the trial that lay ahead, but our positive and optimistic minds wanted to imagine a more upbeat and manageable outcome, and we just had no way of knowing what the DBS had done such a great job of hiding for ten years.

The reality we experienced was draining and potentially life-threatening. The weeks following surgery required vigilance where I was forced to become the triage manager. We had access to medical expertise and world-class care, and yet we felt adrift for much of the time in a vast wilderness—lost and making best guesses based on a faulty road map.

We hope there isn’t a next time, but if there is, we plan to learn from this experience and be better advocates for ourselves. In the meantime, we hope that sharing our story will go far in helping the next person with Parkinson’s and DBS who ends up traveling a similar path.

We would like to thank the author for sharing their story and the lessons they learned with us. If you ever think that there may be a problem with your DBS device, be sure to contact your doctors, relevant care team members and, perhaps, the device manufacturer as soon as possible.

For Further Reading

What’s Hot in PD? Tips for Parkinson’s Disease Patients Switching from Sinemet or Madopar to Rytary (IPX066)

Surgical Site Infections after Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery: Frequency, Characteristics and Management in a 10-Year Period

Life Before and After Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

Sierra Farris on DBS Programming

Life with a Battery-Operated Brain: A Patient’s Guide to Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery for Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease DBS: What, when, who and why? The time has come to tailor DBS targets

Thank you for the wonderful insights. Unfortunately it looks like my father’s IPG infection is heading for a complete removal as well. Your mistakes to avoid was very helpful. I cannot stress enough that everyone select a IPG with a long battery life at least 10 years rechargeable inf necessary to avoid these kind of unwanted infection .