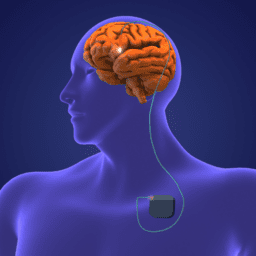

As always, we are so grateful to those who are open to sharing their experiences with the greater Parkinson’s community. In this video, people with Parkinson’s who have been living with DBS (Deep Brain Stimulation) for six or more years discuss why they chose to get DBS, the approval and surgical process, and their top tips for anyone considering it.

You can download an audio file of this webinar here: An Interview with People Living with Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinsons (6 Years) Audio .

You can download a transcript of this webinar here: Transcript 6+ Years .

You can also read it below.

Note: This is not a flawless, word-for-word transcript, but it’s close.

Polly Dawkins, MBA (Executive Director, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Welcome, everybody to our DBS panel discussion with individuals who have experienced DBS therapy for more than six years. I’m Polly Dawkins, executive director of the Davis Phinney Foundation, and I’d like to thank our panelists and our sponsors. I’d like to start by going around the room and asking you all on the panel to introduce yourselves and tell us who you are and how long you’ve had Parkinson’s, how long you’ve had the DBS therapy, and also which device manufacturer you have implanted. So, I’m going to go around the screen as I see you and that’s going to start with Michael.

Michael Fanning (Ambassador, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Hi there. My name is Mike Fanning. I was diagnosed in 2001, so I’ve had Parkinson’s for 21 years. I was I had a DBS surgery in 2015 and it’s Medtronic system.

Polly Dawkins:

Great. Next up, Davis.

Davis Phinney (Founder, Davis Phinney Foundation):

My name is Davis Phinney, and I’ve had PD for going on 22 plus years and had the surgery 14 years ago. And I have a Medtronic Activa, which was the only game in town when I had my surgery.

Polly Dawkins:

That makes sense. Randy, welcome.

Randy LeBlanc (Ambassador, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Hi, I’m Randy LeBlanc. I’m in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and I was diagnosed in 2005 17 and a half years ago at the age of 45. I had DBS surgery in 2018, and 6 years ago. Yeah. And I have the

Medtronic Activa PC also, and that was also the only game in town here in Baton Rouge, at least at that time.

Polly Dawkins:

So, makes sense. Jill, welcome.

Jill Ater (Ambassador, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Hi, my name is Jill Ater. I was diagnosed also in 2005, so I’m like, Randy, I’m at 17 plus years. I had my DBS done 10 years ago, and starting in March, it’ll be 10 years. And I started with, I have a weird system. I started with the Medtronic system, and I switched two years ago to a Boston Scientific stimulator. So, I’ve got what they call a hybrid system, and I switched again just three weeks ago from the Boston recharge the Boston replaceable to the Boston rechargeable.

Polly Dawkins:

Terrific. Kevin, welcome.

Kevin Kwok (Ambassador, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Hi, everyone. I’m Kevin Kwok, now live here in Boulder, Colorado. I’ve had my DBS system implanted since 2013, and I was one of the ones that actually requested DBS earlier on in the course of my disease. I’ve had Parkinson’s now for about 13 years, and the system that they implanted in me was a slightly different one-off Medtronic. It was Activa PC plus S, which was a research device to study adaptive closed-loop DBS, which I bided trials for five years.

Polly Dawkins:

Thank you. Welcome, Marty.

Marty Acevedo (Ambassador, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Hi, I’m Marty Acevedo from San Diego. I’ve been living with Parkinson’s for 18 years and had DBS seven years ago had the Percept d Medtronic system implanted, but with my battery change in August, I now have, I’m sorry, I had the Activa implanted in 2016 with my battery change in August of this year, I switched to the percept stimulator.

Polly Dawkins:

Thank you all for sharing that. So, to start off would somebody tell us, maybe all of you could tell us what your first line of treatment with Parkinson’s was, and then we’ll ask about how you decided to investigate DBS or deep brain stimulation.

Jill Ater:

Well, I started doing medication like I think everybody else did. and you get to a point with medication at least where it’s either not effective or it’s sometimes effective or it causes too many side effects. So that’s when I started looking into DBS.

Marty Acevedo:

I also started with Carbidopa levodopa, and after only three years on, on a very small dose, I had pretty marked dyskinesia. So, my movement disorder specialist was said at the only therapy that he could recommend at that time was DBS.

Randy LeBlanc:

Okay.

Michael Fanning:

Similar experience. It was, I used medication for quite some time, but I, my seizures were so bad that that was the next plan of attack to address the symptoms. So

Randy LeBlanc:

I actually started on a dopamine agonist, Requip Excel. and I was on that for probably three or four years. Well, I was on nothing in the beginning, and that was a pretty miserable time. And then I spent about three years on the REB and then moved to Silva, which is Carbidopa Do and T and then the DBS well, my, I went, well, I think 14 years before I chose to get DBS and the dyskinesia got so bad. I was, I was still working full-time, managing some large projects, and to keep up, I had to take a significant amount of levodopa, the doer drugs, and my movement was just horrible. I moved all the time, so yeah. That’s why I decided to go on DBS. Yeah.

Polly Dawkins:

Kevin, you mentioned you investigated DBS early ahead of that. What was your treatment choice?

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah, you know, they say I’m a pharmacist by background, and it’s ironic because I don’t like medication. I try to minimize it where I can’t. My personal experience was that while I started on a low dose came, I quickly started escalating it, and then I, they started adding domine agonist, and I felt that I was in this uncontrolled state where I was becoming a slave to medication. Yeah. And so, my desire to go to DBS was really to get more control over my life. And so, I went to my neurologist at the time, Helen Bronte Stewart at Stanford, and I went with

a paper that had just been published on the European earlier of patients. And she said to me that, you know, she’d always considered me a patient for DBS, but it was a little bit early at the time, but she said that she would try to advocate for, and that’s what started the whole ball going early on.

Jill Ater:

Kevin, Kevin, remind me what year that was. Kevin Kwok:

2013

Jill Ater:

That was the same year I did it in Denver. Kevin Kwok:

And how many years were you into your Parkinson’s? Jill Ater:

Eight.

Kevin Kwok:

I think when I was considering Parkinson’s or DBS was still considered saving it for the last effort, last-ditch instead of doing it earlier. Yeah. And so, I’m really glad that I liked it sooner than later. Changed my life completely.

Jill Ater:

Yes. Yes. Great. Marty always says it saved her life, and it did give us our life back. Ab Absolutely.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah.

Kevin Kwok:

I’d tell everyone it was sort of like daylight savings time on steroids, it gave me back years of life.

Jill Ater:

Exactly.

Polly Dawkins:

Davis, what was your treatment plan before you considered DBS? Davis Phinney:

Well, back when I was diagnosed, the conventional wisdom, was that Sinemet was to be avoided until later in your course. And so, I went straight on dopamine agonists, which were fairly much of a disaster for me. I felt terrible, and I always was taking three-hour naps in the middle of the morning. And so, the agonist didn’t work at all for me. And so, then I just fairly much issued most Parkinson’s meds for four or five years. And finally, though, I was convinced that cinema would be a good drug choice for me. And so, I started on it, and I had probably one and a half or two really good years where the drug works perfectly. But then, of course, the, you start getting more dyskinetic and whatnot. And I was, I was very quickly escalating from two to three pills to 10 to 12. And so, my dyskinesia and or tremor were just so horrible and so pronounced. And so, I was really happy to have, have the choice to be able to take DBS.

Polly Dawkins:

So, some of you started exploring this idea of what life was like before you chose DBS. I know both Marty and Jill, it seemed to resonate with you that comment. What was going on for you before you chose DBS physically or emotionally, or-?

Jill Ater:

I think what Kevin said, you’re a slave to your medication is exactly right. I mean, I was taking up to 18, I was taking 24 pills a day, 18 of them being ci. Wow. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t. And it really, you know, and then when it worked, I would have the dyskinesia. So, it was always a juggling act. And actually, when they first told me about DBS I said, no way in hell am I going to do this. So, I’m like, Kevin was going for, and I would say, no, I’m not scholastic. I was going to do, and I really did try almost everything else first. I mean to the point I was doing hypnotherapy and I was doing magnet therapy, and I was doing workout three hours a day and all that, and acupuncture and chiropractic and physical therapy, and as well as multivitamins diet changes. I really tried everything, and they all helped, but nothing was long term. And I remember having to find, there was when I decided on DBS after I finally got to a point of saying, you know, it’s either that or jump off a bridge. Mm. I mean, that’s how these Yeah.

Davis Phinney:

And that’s what we hear a lot is that people get to a point of desperation where their medicines are no longer effective, or if they are effective, they have to suffer so much dyskinesia and so much tremor or whatever before they get to that nice calm state. And yeah, I think it, if you’re talking about elective brain surgery, it, you know, it’s a big decision. Yeah. And so, I can empathize with Jill because, you know, it’s just not something that you think of as, as on your bucket list of things to do in your life. But if you do choose that and you have a successful procedure, it was definitely life changing.

Marty Acevedo:

I think my surgeon said to me, oh, I was concerned about neurosurgery. And he said to me, well, Marty, it’s just a, it’s just a procedure. It’s not really that big of a deal. It’s not neurosurgery like, you know, taking a tumor out or operating on a bleeding. And I said, doctor, you’re putting leads into my brain. That’s neurosurgery. It’s a pretty big deal. But I had such a positive outcome, I’d do it again in a heartbeat. That’s great, Kevin.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. You know, one of the things that, to balance it out, right? You know, we all live in this world where there’s a lot of research going on in the bio in the pharmaceutical industry. And I sort of came into this with this idea that even though people are saying a cure is inside any day now the reality of real drug research is its decades, not months and years. And so here was an existing technology that worked, worked well, and many people were discounting it or sort of setting it aside. And I took the opposite approach. I said, why not go with that? And in addition, waited for these new medications to be developed. So, it was really more of a take control now attitude that I took.

Davis Phinney:

Well, and can I ask the panel, did you have someone who had paved the way for you who had had the procedure that you knew of or not?

Jill Ater:

I could only find two people in the whole country. One was Yuma Bev from the Parkinson’s IN’S humor blog. Right. And the other one was a guy I found in Minnesota who had done it, and there had been a local article written about him, and they were both lovely to talk to. And Yuma, Bev, who does this Parkinson’s humor blog, had photos of the whole thing. And she spent time with me going over every process, every part of the process, which made me feel a lot better about,

Marty Acevedo:

I also had someone locally that I talked to. He was active in the Parkinson’s community here in San Diego. And we had breakfast and a number of meetings after that. And he explained, did, as Jill said, explained every piece of the puzzle and the things that might not be helped, like dystonia and some other things. And then since then I’ve been the one that people go to for ab for to learn about DBS. Right. Being it forward. Well,

Kevin Kwok:

You know, I didn’t have anyone either. And it timed well because it was during, just before the decision that I had to make it, I attended the world Parkinson’s Congress in Montreal. And I was like a groupie. I just hung on to all the Michael Oaken and patience and went to all the smaller independent workshops. I think I spent three straight days just trying to talk to patients there. It was a great avenue for learning. Yeah.

Randy LeBlanc:

When my doctor brought the subject up to me, oh, about 20, 20 12, 20 13, somewhere around then. And the only person I knew at that time was actually one of the founders of our local support group. He was he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s at 29. He was a minister. And he, he couldn’t practice, obviously, shortly after he was like the 10th person, the Joe Jankovic at Baylor in Houston. He implanted with DBS. So very early on, but he was struggling when I met him. So, you know, at that time for me, that I’m all about the data and the research and the technical art articles from N I H and there just wasn’t that much out there at that time. And I told the doctor, I said, there is no way in hell you were putting that in my brain. Not going to happen. So, I waited, that was 13. I had it done in 18. Is that Yeah, yeah. 18. And, but

Jill Ater:

Randy, afterwards, didn’t you wish you had done it before Randy LeBlanc:

Or after? Oh, absolutely, I did. Yeah. Does that, like, like Kevin said, that was the last resort at that time, you know, and, but by the time I did it, Michelle Lane, I know very well from New Orleans. She had her DBS I, there were two other, there were two other people in our support group. They had it. But the problem was, after I had mine, I had a couple of issues, and I asked these folks that already had it. I said, where were my friends? You know, tell them, warning me ahead of time. This is, you know, this is what to expect. So, I came back, and I actually sat the four of us down and I made, I did a writeup and I said, I want to know everything that went right and everything that went wrong for you. And we came up with a, I did a writeup for, from the group. And my oldest daughter, who is a semi-professional copy editor and writer for magazines. Got it. And she looked at it and she said, dad, this is like, an engineer wrote it. I said, well, he did. So, she rewrote it in regular English for us. And I give that to everybody. Here’s

what you can expect. You know, so, but yeah, it was very concerning to me in the beginning that there was not that much information.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. Can I add to Randy’s comment? Sure. You know we all hear about the successes, right? I mean, I, after my DBS I completely went off medication for four years and I became such a proponent, I mean, I would blindly go out and just sing the song of DBS to everyone, but, and I became an advisor to patients almost every month, a different patient would reach out to me saying, should I do it or not? And I would always emphatically say, give it a shot. You go for it. Right. And the one thing, Randy, that I’ll, I’ll tag onto what you just said is that in more recent times, I’ve had a few patient friends who’ve not had such a positive experience. And I feel the weight and the guilt of pushing them or recommending them into it without really giving them the full balance story. One of the things that I would love to see manufacturers do out here is not just seeing the praise of those of us success stories, but also provide support with things that go not as well as expected, because they are there.

Randy LeBlanc:

. Yeah. There are, there are too many of them out there as well. Kevin Kwok:

That’s right.

Jill Ater:

Although I do think the percentage is low. If it’s you, it doesn’t matter what the percentage is. You know, I always compare it to your failing a class. If you’re in school and you’re failing a class, DBS won’t necessarily give you an A. But would a C be better than failing? Maybe you’ll get a B. Maybe you will get the A. I definitely got an A out of it.

Kevin Kwok:

I got an A too. But I’ve seen people get Ds. Marty Acevedo:

I agree with you, Kevin. The guilt of being, having had a successful outcome kind of hit sometimes I’m very measured and encouraging someone, I say everyone’s different, and we all are going to have different outcomes. But it’s more than just a device manufacturers, it’s the surgeon. It’s the experience of the surgeon getting to the right spot in the brain that the sweet spot in the brain that they need to get to. And then the programming after that, if that’s done

appropriately by the movement disorder specialist or whoever’s doing the programming. So, there’s a whole team of things that have to go right for DBS to be successful.

Randy LeBlanc:

Right.

Kevin Kwok:

It’s true.

Michael Fanning:

I’ve been very careful about what I tell people about with my DBS and as I had friends of mine who have had expectations that were not met when they had your DBS surgery. So, my comment to people is, don’t expect to come out with anything. Come out. Hopefully, hopefully you can come out with it coming out. No, no words. Often when you went into surgery. And then everything, every positive that happens is a blessing. So, so you don’t have the expectations of what’s going to happen. Everything is a blessing. So that’s,

Polly Dawkins:

Yeah. I think that’s what we hear about setting realistic goals. Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah.

Polly Dawkins:

Yeah. So, when you think about what your goals were for your DBS surgery, do you all remember there’s been many, many years since you had the first since you had the implant. Do you remember what your goals were for that or where you were, how you were feeling and what you hoped to feel afterwards, what you hoped to change?

Davis Phinney:

Yeah. I mean, I wouldn’t call them goals. I would say I had hope that I would get some relief from my tremor. And then when I was in the OR, and I was thrashing around all over, because you can’t take your meds beforehand and you’re pretty miserable and your head’s blocked-in place and every other part of your body were going nuts. But when my neurologist, which it was also Kevin’s neurologist, hell, I said, well, let’s just see about the placement of this lead and let’s put some juice through the light. And it was just like this instantaneous, ah, and all that crashing, all that tension went away with one of the most profound experiences of my life. And

so then, then I had the taste of what it would be like when they even eventually programmed me. And the programming was straightforward enough that I was able to walk out of there with my hands, but my side, instead of in my back pocket or, or my tremor tactics were all able to be put aside. And that’s what was, so that was the miracle of that day.

Jill Ater:

Yeah. You know, I had less of a tremor, more just pain and stiffness and I just wanted to stop hurting and to sleep. I was only sleeping about two hours a night. Yeah. Since I had DBS 10 years ago, I can sleep 9, 8, 9, or 10 hours without even waking up. Wow. Every night.

Davis Phinney:

Do I

Polly Dawkins:

Remember you were also maybe in a wheelchair. Is that true, Jill? Jill Ater:

For a while, I was right before at the end, because I was in so much pain. Hmm. Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. That sleep thing, they, they kind of warn you going into it that they, they don’t expect to see it. But it was a very pleasant addition in my life too, Jill. It is sort of, there’s, there’s a bunch of things that I don’t want to overclaim, but I think we all react differently to DBS. And we all see different benefits or complications, which are not the same amongst all of us.

Jill Ater:

Well, and the other thing I think you have to remember is it’s not a cure. I mean, we’ve all seen over the years our Parkinson’s has gotten worse. So, I did the same, I cut down because I had mine in the Subthalamic nucleus SST N which they’re doing less and less of now. But when I did that, I was able to cut my meds down from those 18 pills. I was taking a came to zero.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. I’m like you. Jill Ater:

But now, but over the years I’ve gotten more and more and more I’ve added back in. I don’t take came and I take rotary, but I’ve had, now I take four a day.

Randy LeBlanc:

.

Kevin Kwok:

Do any of you ever turn your DBS systems off? Jill Ater:

I had to do it recently when I had, before I just got my new rechargeable battery and before that I, my surgery I had to have a keg, which was all about two and a half minutes. They had to turn it off and immediately, you know why you have it. Right. It’s like okay, got it. Reminder

Kevin Kwok:

. I mean I feel I used to use it for stupid human tricks to show people. Right. And I don’t do it anymore, but it’s so profile when you turn it off that you realize how much benefit you’re getting that you, you’ve just taken for granted. Otherwise,

Randy LeBlanc:

I do it on occasion. My wife gets very mad at me when I do it. Yeah. My girl, I do it for the I work with the local PT college and their nursing school, and I will turn it off to show them how, how it, well it works also, I attended one of the graduate courses at LSU or kinesiology. And when the professor there was a very good friend of mine and when they teach the Parkinson’s unit, she asked me to come in and I turn it off for them and show them the difference. And it’s amazing. Now, I did not have resting, resting tremor. I have the bradykinesia and it’s a real slow movement. And so, when I turn it off, I, you know, you end up stooped over and shuffling. But

it’s not as dramatic as the resting tremor because they, they, our local new medical center has, several of my friends are on there and one of them, I mean he’s, he’s doing like this and the doctor turns it on and he stopped, you know, for me, I was about half an hour in the programming room with him and he said, walk down the hall, said, okay, you good, you can go home.

Randy LeBlanc:

I said, but what’s different? My wow moment came the next morning I woke up and went to make a coffee and could, didn’t have to wait for my meds. So yeah. And I also went from about, well, 1600 milligrams of, of do levodopa per day, which is zero for over a year. And now I’m coming back to, I mean, I take more and more as time goes on, but yeah.

Jill Ater:

Well because that, it goes back to the fact that it’s not a cure. Randy LeBlanc:

Right. Right.

Davis Phinney:

Well, and don’t you feel that people who don’t understand what it’s like to live on an on-off cycle don’t get why, well, why wouldn’t you just keep taking some medicine? Right. And that whole goal that we all had, which was to get off medicine. Sure. That, I would say was a goal as well. And I was able to achieve that for five years. And now I also only, I take very minimal amount of Rytary. Until twice a day. But not having the dyskinetic effect and not having, and of course not having any tremor at all is really what allows me to sleep. And so, I would say that, well, it’s not a cure and it never will be. It’s, it feels almost curative to get that decent night’s sleep and not wake up every 20 minutes and start tremoring or be in pain or whatever. Marty?

Marty Acevedo:

The improvement in my quality of life was so profound that, you know, I can’t, that’s why I say I got my life back. I was able to start exercising again, which allowed me to do a lot of other things and improved my balance. I wasn’t following anymore. I take two meds right now and since, and I had DBS seven years ago, but I only take two: one for dystonia and one for Parkinson’s. And it was just so immensely positive for me to have DBS within my type of Parkinson’s is different from everybody, from most other people’s. So not everyone’s going to have a really robust response. Kevin?

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. I went back and looked at my medical chart from Stanford and what it said was the target goal was a 30% improvement, but I’m not really sure what they meant by 30% was

Jill Ater:

Over what Kevin Kwok:

U P D Rs

Davis Phinney:

Then you Yeah, exactly.

Kevin Kwok:

Reduction in meds, quality life. I think it was a combination of all of them. But like Marty, what happened was, because of that great feeling that I initially got from DBS, I started exercising feverishly like crazy. I also switched jobs to a less stressful job. And I was sleeping better. So, I tell everyone, DBS allowed me to do all those different things and my <inaudible> of it all is what made my life so much better.

Jill Ater:

Right. Yeah. My husband always says it gave us both a second chance at life. Kevin Kwok:

Right.

Jill Ater:

Which is why we’re now moving to Portugal. Davis Phinney:

Awesome.

Kevin Kwok:

Can we come visit?

Jill Ater:

Absolutely. Kevin’s two-bedroom place ready for Randy LeBlanc:

You? I’ve already signed up, so didn’t Jill Ater:

Want No, but that’s the thing is when I travel, nobody knows I have Parkinson’s. Yeah. I mean that’s the biggest difference because they don’t, they can’t see it. My voice is slowed down. My, I do use walking sticks when I’m traveling, but you know, I can go out at night and sit somewhere and nobody can tell there’s anything wrong, which gives you a lot of personal satisfaction, like getting a good haircut. You know, you just feel better around people.

Randy LeBlanc:

Not, not all of us can make it look as good as you do. Jill Polly Dawkins:

So, Mike, how has your life changed since D bs? Michael Fanning:

I didn’t get a chance to try to, my dyes are so bad that I thought I was going to try out for dance with network, dance with network stars didn’t a to do that. So, DBS was working for me, but you know, humor has got to be a big part of my life. I just, if you’re not laughing, you’re crying. I would rather laugh and exercise a little bit than cry and be sorry for myself. But yeah, so, but I was taking almost 27 or 28 CI a day before DBS and when DBS, after I had DBS, I dropped down to six or five for the next few years if I’m back up with, you know, with the vitamin has gone up again because it, just, because it’s progressive disease, but always life is good. So, I’m just, it’s a blessing. They had the surgery.

Davis Phinney:

Well, and can I ask any, everyone to weigh on how much their programming has had in effect and how much of their medicine need came back into the picture?

Jill Ater:

Well, I always explain it that it’s a balance. So, if you’re between the programming and the meds and you, everybody, as Marty said, everybody’s different and you’ve have got to work with a really good programmer. So that’s really what probably the most important of all of them. I think actually I call it the five six Ps, and which is the product that because there’s many, there’s just, there’s not just Medtronic’s and Boston Scientific. There’s another company who I can’t think of right now.

Marty Acevedo:

Abbott. Jill Ater:

Abbot Abbott. There’s the physician is the second p who’s the surgeon who’s doing it. Do they know what they’re doing? And I would always ask to talk to one of their patients. The placement. Do they, where is it going in your brain? Is it going in the STN or the GPIY? And why would your doctor do that? Is it just their standard or is it better for your symptoms than the programming? The, probably the most important is who’s doing the programming. You should know that in advance. Yes. And do you have somebody who knows what they’re doing? Is the rep for mine? My doctor’s great, but she also has my rep come in every, the Boston Scientific

rep is there for every programming session, which is great because she knows the latest and the best for me, the patient, which is you will you take advantage of this?

Jill Ater:

And are you honest in the programming? Because the programming depends on you saying, well, it doesn’t quite feel right. I feel a little pull on my lip or my throat hurts or my left thigh. Because you have to be really tuned into your body. And then the last p I think is the family support, which, that’s the people. People, people. And that’s support because it’s not an easy surgery and it’s, I mean, you’re still out for a while and you have to deal with, well I know the bed don’t care as much, but for me it was a big issue to have my head shaved, even though they didn’t do the whole thing. But a lot of people, that’ll stop you because it’s a, you feel more major than it is.

Marty Acevedo:

My programming was, has always went up on my movement disorder specialist. And they didn’t turn my left side on for the first five years because I was so left-sided predominant with Parkinson’s. We turned it on last October because I was some dystonic changes and the, my previous movement service specialist did some programming that made me a lot worse. And when I reported back to her, she said, that’s not what I, that didn’t have anything to do with my do with what I did with your DBS. So, I switched doctors, he made some slight changes, and everything just was great again. And just this last week, I had have been having a little bit more dystonia than my left hand and he made a slight adjustment, and it cleared up just like that. So, it’s what Jill’s saying about the five P’s is so important. You have to know your own body; you have to have a great programmer physician and you have to have someone who’s going to listen to you and work with you and put the patient first.

Jill Ater:

.

Marty Acevedo:

Yeah, Kevin. Kevin Kwok:

Well, you know, one, one of the Ps, I like your P rules, the five P rules are in the placement and the actual surgery. One of the pieces of advice that I’m giving to people is I used to have great respect for the teaching hierarchy in teaching institutions where you had, you know, the main surgeon and then you had fellows and residents and others being part of the team and they’re actually in the suite when you’re having your surgery. But I think seeing what I’ve seen with

complications in other people, I’m less apt to want someone to be learning on the job. picking probes in my head. And that oftentimes happens. It’s like, do you mind if we have the fellow or the resident, you know, work on you? If it were me know I would be a little less trusting of that situation.

Randy LeBlanc:

Alright.

Kevin Kwok:

It’s a little different with the programming side because there’s a little lot of hit and miss there, but the precision of getting the lead in the right place is not something to be played around with.

Marty Acevedo:

Yeah. Right. Agreed. Randy? Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah. So, I’m following up on a couple of the points that were made here. I agree with Kevin. I don’t want any on the job training on my brain. They, they can look, watch, but don’t touch our, our, we have a, a neurosurgeon here who is second and none according to the Medtronic guy, but I guess he would say that. But no, their success rate has been extremely good. And it’s location, location, location where they put those probes is very important. But to answer Davis, you answer your question on programming, that was key for me. And in the beginning, well what my doc, my movement disorder specialist did, when he programmed me, the 30 minutes he spent with me and then sent me home, he said, here I gave you a full range of adjustment capability on your amplitude or voltage. And take that and come back in six months and tell me what you did.

Randy LeBlanc:

Knowing full well that I would research the heck out of it and do part, part. We’ll let, yeah, let me watch what I say. But it’s so I did, and it worked out fine for about a year. And then I started having falls. My speech really deteriorated terribly. It’s a little rough today because I didn’t sleep too well last night, but generally it is not terrible. But you know, then I started researching that and I found out that you could program differently. Well, about a, I guess this was maybe last year, oh, about a year and a half ago with my involvement with the Davis Phinney group, I pulled together my own panel of experts. Marty was one, Kevin was one, Jill was another one. And I, we talked through issues I had, and I got some advice from these good folks here.

Randy LeBlanc:

And I went out of my comfort zone, and I went to a second opinion to Dr. Baylor in Houston. And she put one of her residence working with me. And he basically stripped me down to nothing. And he started stair stepping all the, all the parameters up. And when he got there, you know, I wanted to eliminate the falls where they improved my handwriting, they improved my speech, they improved my falls. I mean, those have virtually gone away. So programming is very important, but I think one of the biggest responsibilities of the patient is first of all to understand the basics of this, of the components of the signal. And I don’t expect everybody to be engineers. I am an engineer and I understand it, but I branch to my doctor. He says, well you give me too much credit. I don’t, I ex I have high expectations. But yeah. And then like, like Jill said, you’d have to be honest about what you’re feeling, and you have to be your own advocate there. You have to be relentless and tell him, no, this is not working. You know, this is not as good as it gets. If that’s the answer, go somewhere else. Yep. Davis?

Davis Phinney:

I mean that’s two really great points. One being that you need to be able to be brave enough to change doctors or change programs if that’s needed. And it’s not even necessarily a knock on your original programmer. But they, they, they only know what they know in terms of their experience and their success with programming you. And so sometimes changing doctors just gives you a, a fresher different set of eyes. looking at the problem. And so, I agree with Randy that that’s really very important. Right.

Kevin Kwok:

Davis, you, and I have talked about this because we’ve had similar programmers and surgeons, but sometimes, and I don’t know what the rest of the panel experienced this is that when we go in for our programming, sometimes the positive in out input that we give to our programmer doesn’t really relay how we’re feeling 10 minutes after we leave the office.

Davis Phinney:

Right. That’s because we like being rock stars when we walk in and we like seeing them, them seeing us in our birthday.

Kevin Kwok:

And I think that’s exactly right. Jill Ater:

Right. Well, that’s why I use a lot of logs. I keep an ongoing log list so that I have something to, you know, we have in the Davis Phinney book in our every victory counts worksheets. What to

Talk to your doctor about? No. When you go for your appointment. I don’t remember what’s that one call Polly, do you remember

Polly Dawkins:

How to prepare for your doctor’s appointment? Right. Yeah. Give me that one. Jill Ater:

So, I keep an ongoing list on my phone and then I make sure that I come in with that and so I don’t forget so that when I’m frustrated when I’m not in the doctor’s office, I have something to refer to.

Polly Dawkins:

Yeah. I’d like to talk about this topic that some of you had touched on about complications. I’d also like to talk about you or ask you all about your sort of maintenance. How do you, what do you need to do? So, let’s, let’s start with sort of the annual maintenance of your deep brain stimulation. What do you have to do? How often do you have to get a battery replaced or adjustments made? So, starting with Michael, tell us what your experience

Michael Fanning:

Is. My first surgeries were done with regular batteries. I went to rechargeable ones after having my batteries replaced three times on each side. So, my batteries lasted less than three years.

HB is intensity was turned up so high. They were less than somewhere between 18 months and two years. So, the last batteries I had went to go to rechargeable batteries. So

Polly Dawkins:

How’s that going? Michael Fanning:

So, it’s going well, but you know, it’s a little bit of work. I mean, just you have to recharge your batteries about every, you know, it was seven days or so and the time it takes is you can even recharge them like a little bit every day or you’re taking, doing it once, once a week and then it takes like four or five hours a time to do it once a week. So yeah. But it takes a little bit of time. So,

Jill Ater:

Can I follow up on that Michael? Because I just switched to a rechargeable one.

Michael Fanning:

Sure.

Jill Ater:

And it takes, mine takes an hour last night for the first, for the third time once a week for an hour. My, and one of my concerns was having to do it all the time because I know that the system, my mother has the same, she has a rechargeable and has to recharge every day. And that I didn’t want that because of my travel. And they said mine can go up to four weeks without it.

Polly Dawkins:

Wow. Well, that’s great.

Kevin Kwok:

Is it any different than recharging your phone? Jill Ater:

No. You know what, if you excuse me, I’ll run and get the things you can see. It’s right in my room.

Polly Dawkins:

Well, you can walk away from your phone Kevin Kwok:

More just the burden of, of charging. We all get more phones charged all the time. Jill Ater:

Right. But you know what, I think it’s a matter of figuring out how much power you individually need so you don’t get that, what they call range anxiety.

Randy LeBlanc:

.

Polly Dawkins:

Wonder if it’s like driving an electric car. Exactly. Run out.

Jill Ater:

Exactly. But then I also now don’t have to worry about travel and getting back to change my battery. because like Michael, I was changing every two years.

Marty Acevedo:

So, my first battery change was in August and that I had the first one for six and a half years. So, I don’t use a lot of my bet I don’t have a lot of battery usage, so I don’t have much maintenance at all on a regular basis. I just see my movement disorder specialist every three to four months. We, and we may, may or may not make some programming changes during that time.

Polly Dawkins:

Thank you. Davis, what’s your experience been with changing out or maintenance for your system?

Davis Phinney:

Well, first of all, I had to give my unit a name, so I call him Bob and now I’m on Bob four after all these years. But I mean, I had my first battery change probably five and a half years in, and then it went down a little bit from there. But I’m still going on four plus years with this, with this rendition of Bob. And so, I see my neurologist and or his is pa probably once every three to six months. I mean neurologists, I’ll see. Yeah. Maximum one twice, once, or twice a year. But the PA is a real godsend for Kevin and me who, who also shared the same neurologist here in Col, Colorado.

Polly Dawkins:

And Randy, what’s been your experience with replacement or maintenance that you have to do?

Randy LeBlanc:

So, I’m still on my original battery. Well, it’s six years I was concerned. In fact, Jill and I had a conversation yesterday afternoon about you know, the traveling with your battery. And I’m take her advice and wait to get on the road again, but until my battery gets changed that there’s some complication with the insurance company. They, they want you to hit almost rock bottom before they’re going to pay for the change now. And I don’t know, I don’t know how it was early on, but anyway, it’s I mean, as far as maintenance goes, I see, well I’ve had quite a few appointments late over the past year because I went for my second opinion, and I was actually homing in on the same answer with my neurologist with the research I had done.

Randy LeBlanc:

I would go in and tell him, let’s tweak here, here, here. He’d make the changes, but you’re the limitation the patient has, it was going to take five years to get to that solution. So, I told him I don’t have that kind of time. So, I got, got tell another neurologist to do the programming.

Since then, they really have not changed it at all. I will go up or down a little bit, depend on how I feel on a given day. Sometimes I get restless leg in the evening, I can tune that out a little bit. Or if I get little dyskinesia, I can, I can tune it out. You know, sometimes, not always. So, I’m pretty active in using my patient programmer or programming abilities to try and optimize my life with it. Yeah.

Davis Phinney:

Does anyone else do that? They use their home programmer? Kevin Kwok:

I never

Randy LeBlanc:

Touch it.

Davis Phinney:

Me need Randy LeBlanc:

People in my experience don’t know where they keep it or. Kevin Kwok:

I think I’ve lost for them that I’ve used them. Yeah. Yeah. Polly Dawkins:

Michael, do you? Yeah, it’s yours. Randy LeBlanc:

What’s that?

Polly Dawkins:

Mike, do you use your programmer to change your settings?

Michael Fanning:

No, no. I’ve got the opportunity to change it, have the opportunity to use it, but I don’t do it. Polly Dawkins:

Yeah. Sounds like Randy’s the only one here who does that. Yeah, Kevin? Kevin Kwok:

I had an interesting situation where I came to, I’ve had two battery changes. My last one was in 2020. And I was really hoping that technology would advance where the newest one would be available at the time that I was switching out batteries so that I could go to an adaptive DBS system. But unfortunately, it wasn’t ready yet. And I didn’t qualify for any of the studies that were going on to resume the research device. Right. So, I had to elect to go to a battery. That was the shortest last thing because I owe you want insurance to cover it at the end when you do switch out. And so I went to a device that would last hopefully just two to three years. And at the next switch, I’m hoping that technology and the approvals of adaptive d s will catch up.

Jill Ater:

You know what, on that note Kevin, I was concerned about that, especially going to the rechargeable because it’s good for 15 years, they say Exactly. And I don’t want an iPhone seven when they have the 15 coming out

Randy LeBlanc:

, right? Yeah.

Jill Ater:

But they said they did. My doctor and the rep book from me, from Boston Scientific both said that Medicare at least will now cover if the technology would make a difference in your treatment, that they will cover a new change even if you don’t technically need it.

Randy LeBlanc:

Right. I’m Kevin, I’m glad you brought that up because I had the same thought process and I’m probably not going to go with the rechargeable next year, and I get mine changed for that reason. But the pro well had, had I known where the technology was going to go, of course, he has, if I had that crystal ball, I wouldn’t know. Yeah. Anyway, so but yeah, if, if we had had the directional probes that I would’ve jumped on that quickly, the segmented probes. that Boston came out with, and that Medtronic has since copied. So, it yeah. So, the but the technology is

changing so fast. I’m curious, but the problem is, you know, what’s in your brain is the key right now,

Marty Acevedo:

You know, with I have a new percept Yeah. Battery from Medtronic and it has it can store data and that type of thing that does drain your battery sooner. But the next level of technology that’s coming out will allow the device to be, to do more. I don’t have a directional leads and all of that, but still the new, the new technology and the battery itself are going to be pretty, pretty cool. Especially with the management of dystonia, which is my IMOs significant problem at this point.

Randy LeBlanc:

Right. But they, they can also do some current you know, they, they can split the current Marty Acevedo:

Right.

Randy LeBlanc:

Different probes and there are some advantages, but it’s not nearly as big as it would be if we had the option had had the option. All of us, obviously none of us have the segmented probes

Polly Dawkins:

Since you all have had it for so long. Yeah. Yeah. I’m going to ask another question and then begin to wrap up. But actually, two more questions for you all. If you have the time then well Jill shows off her rechargeable recharging unit there. Well,

Jill Ater:

Let me just show you. This is the unit that stays plugged in and you just pop this out, stick it in, and it just sits over your shoulder,

Polly Dawkins:

Right?

Jill Ater:

And that’s it. That’s how I read Polly Dawkins:

Yours is like Mike’s as well. Pretty similar. Michael Fanning:

Mine, it’s a little bit different than that. It’s more of a holster than anything else. And then a sling. And so, if, if it’s not saying exactly where it’s supposed to, it’s, it doesn’t, doesn’t it doesn’t recharge this effectively. So, that’s why it takes a little bit longer because you have to really see, be saved very still for quite a bit of time. So, it’s still a bit different and-

Polly Dawkins:

But it looks like you could walk around and vacuum Davis. You could do your vacuuming if you want.

Jill Ater:

Vacuuming might be hard because, yeah, it’ll beep at you if you’re on if it moves off of your side. Yeah.

Polly Dawkins:

Super. All right, next question for you all. I know sounds like Mike has had the most surgical battery replacements in the time, but, and maybe Davis has had the therapy for the longest. Has anybody had any major malfunctions or complications that you’d like to talk about? Davis.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah.

Polly Dawkins:

What was that Davis? Davis Phinney:

I mean, I had a nightmare a few years back where, where I developed an infection around the unit itself in the tissue. And so, we determined that it needed to be pulled out asap and it proceeded to lead me on a crash of epic proportion where I went from, you know, full power to no power after some 18 years of having had that power. And I was taking, again, very minimal meds. So, when I was in the hospital, they would only give me two Rytary, which I needed about 50 at the time. But because of doctor’s orders and whatnot, we had this, I mean, it was a real crisis for me for oh, a few weeks where I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t move, I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t do anything. And that eventually resolved itself with enough medication to offset the DBS unit. However, when I got my unit back after three months, after the six weeks

of IV antibiotics and whatnot, and I got my, it was just like that same sense of a miracle was relived. And so, I mean, I have an absolute appreciation for what my DBS can do for me and what I would be, where I would be without it.

Jill Ater:

Davis, can you clarify? They didn’t take just a stimulator out where the infection was. They took the leads and everything, right?

Davis Phinney:

No, they left my leads in, but they then told them back and my skull and so my leads were left intact and otherwise, I would have had much more of a major surgery.

Polly Dawkins:

So, the infection was contained in the- Davis Phinney:

Yeah. Right at the battery site. Exactly. Jill Ater:

Because I think our friend Bart had to have the leads taken out. He did. Right? Davis Phinney:

He did, right. And that’s the case with most infections from what I understand is that they can travel very quickly to the brain, but mine was outside of my unit and so it was a little bit different than something that would be internal in the wire.

Polly Dawkins:

Has anybody else had complications or malfunctions? Kevin? Kevin Kwok:

I’ve had a couple of situations where the leads were switched. And so, they were mislabeled, and they were stimulating the wrong side of the brain. It was almost more comical and humorous than it was dangerous.

Polly Dawkins:

Was that programming switching?

Kevin Kwok:

I’m sorry. Polly Dawkins:

Was that a programming switching? Kevin Kwok:

I think it was a mislabeling from the original surgery. And so, e every time someone knew, got a hand on the programming, they sent the convention back to what they thought was the original. The question that I have for the panel is what’s next when our DBS is not as effective anymore? What’s our recourse? What can we do? And then, I’m sort of entering into that phase now where all the joys and the, and the, and the privilege of, of living good life is starting to erode away. And I was told by my neurologist here at CU that seven years is kind of the glory years. And then after that, the progression of the disease starts taking over. And I just am curious about what others are thinking about. How do we make that longer?

Jill Ater:

I’m at 10 so I wouldn’t say mine’s over by any means. Kevin Kwok:

I want to be like you. Yeah. Jill Ater:

I’m, so I’m already speaking her head as well. Marty Acevedo:

I think that, you know, the ability to exercise can maybe stave off that or make that length of time longer. We all know the benefits of exercise, so that helps. And again, I’ve said this over and over, but we’re each different. My progression is very, very, very slow. So, I probably have, you know, much longer than seven years where someone else might not have this, have that.

Randy LeBlanc:

Kevin, you’re talking about seven years on DBS or seven years of Parkinson’s.

Kevin Kwok:

No, I’m 13 years in Parkinson’s. About eight on DBS.

Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah, I am. Jill Ater:

I just think that’s a doctor who’s putting all their patients in one basket. Yeah. Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah.

Jill Ater:

Because how many people have been told when you were first diagnosed, you only had 10 good years left? At the very beginning. And we’re all past that, so well past that. Yeah.

Marty Acevedo:

A positive attitude goes a long way too. If you stay positive and just, you know, don’t give in, and keep, keep living your best life, then I think that has, that has to have some effect on, on how fast quickly you progress and how your symptoms get worse or better or whatever.

Davis Phinney:

Well, and also, I mean, Marty, don’t you feel like that if you prioritize your exercise and you prioritize your sleep and you prioritize your lifestyle, that that is, it gives you your best life as you would say, and then you’re prolonging that good effect.

Randy LeBlanc:

Yep.

Jill Ater:

The other thing is you, with Parkinson’s in general, I think it teaches you to appreciate and live fully every moment. Yes, for sure. Well, you know, we’re all going to die someday, so you might as well enjoy it. And I think for many of us, we were young enough when we were diagnosed that we didn’t even feel that coming on. I was 42, my kids were only four and seven years old. And so, since then I’ve learned to really appreciate every day of life and not squander it. And then having the DBS gave me round two of being able to really enjoy things.

Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah. I would like to say something in general about DBS. You know, I hear from a lot of people who fear it, and they I mean we have several of the ambassadors who’ve had discussions with and where they, they just flat out won’t even consider it, but they will try other technologies, it’s too, to me, are not nearly as effective. And because they hear us complaining about programming issues or whatever. And I want to say that it really angers me that we don’t, you know, show, show the positives enough of the d b DBS out there and the, I mean, we do have, it is not perfect by any means, but nothing is. But you know, to have them discount it so readily, to me it is a frying chain because it’s a great technology. You know, whatever programming challenges I had, I mean that was just another fun opportunity for me to play with my brain.

Jill Ater:

You know, Randy, when I think about, I think about people having the Duopa system, which sounds like a pain in the rear. You know, that’s a lot of work and a lot of that hurt. And then the injections that some people are doing, that’s also a lot of work, a lot of effort. And I don’t want, I get up every morning and don’t have to do a thing

Randy LeBlanc:

Right, exactly. Exactly. I agree with it. So, but yeah, I think, I think that it needs to be advertised as the positive thing that it is, and you know, ultimately if it doesn’t work for you, turn it off.

Jill Ater:

Right.

Randy LeBlanc:

Okay. So, you I wouldn’t go so far as to say yanked it out, but it can be if that, so Yeah. Well Davis Phinney:

I mean my only caveat to that, is Randy. is what Kevin said earlier, which I really believe is true, is that we can, even if we’ve all had tremendous results from DBS, we can really only speak for ourselves.

Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah.

Davis Phinney:

And push it on people because I, like Kevin was originally a big, huge ambassador for DBS. and just say, you know, I could just say, I mean my truer went from that insane level to this.

Randy LeBlanc:

Right.

Davis Phinney:

And people would say, well, I want, you’ve got, but not everyone has had a great result and or even a good result. And so, it is something that you just have to add the caveat for me. Yeah. Or in my case,

Randy LeBlanc:

Right. Just to be- Davis Phinney:

Honest.

Randy LeBlanc:

Yeah. I do that with everything. I’m, too- Jill Ater:

Me, I’m not a doctor- Randy LeBlanc:

But I’m not a doctor experience. And I tell them locally, do not ever go to your doctor and tell them Randy said, because they get very upset about that. So, I don’t give medical advice. I give exactly what you said, Davis. The caveat is this is my personal experience with it. But you know, it, to me, we, it needs to be, have a more of a positive spin on it.

Jill Ater:

Yeah, I mean, I think of, I’m like, Randy, I think there are hundreds and hundreds of people I know who’ve had successful DBS. I know maybe two, or three people who haven’t. And theirs has been pretty miserable. And I wouldn’t want to be one of those two or three, but the hundreds and hundreds I do know who’ve had success. I think that speaks a lot.

Kevin Kwok:

How, how many, this is the end on the lighter now, but how many have had your calves, counters, and sun for cosmetic reasons?

Davis Phinney:

I think you’re, you’re one of the only people in the world kef who doesn’t have those nights. The horns by the god of your head.

Kevin Kwok:

Well, Michael Koen said to me when I walked out of his workshop when I asked him what physical things happen to you. And he says, we use the technique of countersinking where they’re flush. You don’t even see the calves on there.

Jill Ater:

And I think they do that. The new ones all do that, don’t they? Do they? That’s what I’ve heard. Kevin Kwok:

I mean, I like shaving my head now, you know, because I like to show that this is my mom. Every time I shave my head, it’s my reminder. It’s my pink ribbon for living well with Parkinson’s. And I’m so grateful for DBS for giving me that.

Randy LeBlanc:

I kept my head shaved for about two years after I had my surgery and, you know, and my, I was going to get my little horn tattooed like a buckle. No, I wasn’t really, my wife and my grandchildren shamed me into laying my hair grow back out. So, you can’t even tell they had DBS. But yeah, I mean, I advertise, I always tell my story, so that’s not a problem. But yeah, it’s but you know, for me, it was a life changer just like Jill and Marty. Yeah. And really everybody

else. I mean, it’s been a great ride for me. I would continue, I would do it again in a heartbeat. Jill Ater:

You know, I always say I do it every month again. Yeah. That’s how successful it’s been. Randy LeBlanc:

I reminded my neurologist the other day. I said I tell this story. When you walked into the operating room, the neurosurgeon had, he was getting ready to drill into my sculling thought my moving disorder specialist came and put his arm on his hand, on my leg. He said, man, I love the smell of burning bone in the morning. That was the mood in the operating room the whole time. But yeah, there’s a picture. Yeah. But you know, it’s like, like I said, well, I don’t know if you remember this Davis, but we were, we were in New Orleans at the first walk that Michelle did for you guys. Right. And you and I were talking, and they started the Zumba warmup before the walk. Oh,

Davis Phinney:

That’s

Randy LeBlanc:

Right. And I said, well, you know, I went through five surgeries not to move like that not on purpose. I’d be darned if I’m going to do it on purpose.

Davis Phinney:

That’s awesome.

Randy LeBlanc:

It is,

Davis Phinney:

I remember. Randy LeBlanc:

That’s been good. Been very good. Polly Dawkins:

Before we wrap up here Michael, it looked like you had something you were going to say. Yeah, no, no. All right. I’m going to bring,

Jill Ater:

I give it two thumbs up for DBS. Yeah. Polly Dawkins:

It looks like all these two thumbs up as we close out here. This terrific conversation. Thank you all. Is there anything that you’d like to end on that I haven’t asked that you’d like our community to know?

Jill Ater:

You know, the one thing that did occur to me, we, we talked about programming and as Randy said, he was told to come back in six months. Those six months I think are key. And the good programmer’s going to see you several times during those six months, I think to get that right.

It’s a get, you don’t walk out and feel great. Not everybody does. Sometimes it takes that whole time to get it right, but give yourself time,

Polly Dawkins:

Be an advocate patient.

Davis Phinney:

And one thing that we didn’t touch on poly, which gets us more into the DBS weed, but it’s still I think, important with bilateral versus unilateral and who’s had what surgery,

Polly Dawkins:

What do you have bilateral? Bilateral? Randy LeBlanc:

Don’t know. Polly Dawkins:

That’s nice.

Kevin Kwok:

My feeling Davis is that it’s like when you’re constructing a house and you’ve torn down all the walls, you might as not do it twice. You might as well wire for speakers once.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah. I mean I had two Jill Ater:

Separate, I had totally two separate surgeries. I did one side and then 17 months later did the other side. So, I had two unique systems

Kevin Kwok:

There. There are some investigators out there that feel that DBS can actually be disease- modifying. I know they’re doing those studies at Vanderbilt with Dr. Charles. and so, for me, I wanted to see if my lesson-impaired side would be, would progress slower. I think it’s a little early to make the claim that it is a disease modification, but I had that curiosity.

Davis Phinney:

Yeah.

Polly Dawkins:

Well, everybody thank you so much. Thank you to Michael and Randy Davis, Jill, Marty, and Kevin for sharing your experiences.

Jill Ater:

Thank them for inventing these things. Polly Dawkins:

Yeah, thank you for, exactly, the scientists and researchers for inventing this technology. And if you have any questions for our team at the Davis Phinney Foundation, you can always send those questions to us at blog@dpf.org. And until our next conversation, we wish you all the best and thank you all for being a part of this conversation.

Want to Learn More about Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)?

You can find a wealth of resources about DBS here.