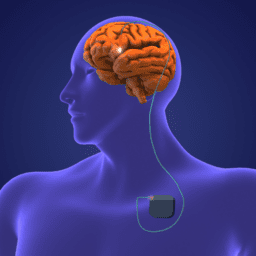

We recently sat down with a panel of people who received deep brain stimulation (DBS) within the past three years. Each of them shares their story, and we discuss why they chose to get DBS, the approval and surgical process, how programming went (is going), and their top tips for anyone considering it.

You can download an audio file of this webinar here: Audio 0-3 Years .

You can download a transcript of this webinar here: Transcript DBS 0-3 Years

You can also read it below.

Note: This is not a flawless, word-for-word transcript, but it’s close.

Melani Dizon (Director of Education and Content, Davis Phinney Foundation)

Hi, everybody. My name is Melani Dizon. I’m the director of education and content at the Davis Phinney Foundation, and I am here today to talk to people who have been living with deep brain stimulation, or DBS. They’ve gotten somewhere within the last three years. And we’re going to talk about the ins, the outs, the good, the bad, the ugly, and everything, how they decided on DBS, the process of getting DBS and the approval process, the surgery itself, healing, programming, all of those different things.

All right. So, I really would love to get started by just going around, I’ll call you out based on how I see you on my screen and just introduce yourself by sharing your name, your age if you’re comfortable, years of living with PD, you can either say I’ve had symptoms for such and such a time or my clinical diagnosis was in such and such a date, years of or when you got DBS in particular and then the device that you have. All right. So, I’m just going to go around as I see you, Bart.

Bart Narter:

Hi, my name is Bart. I was diagnosed in December of 2011, and I had DBS in January of 2016 and then again in May of 2021. I had it done two times because the first time it got infected, and we had to take it out kind of immediately. I think I’ve answered all your questions, but if not, tell me more.

Melani Dizon:

Yes. Which device? First time and second time. Bart Narter:

The first time was Medtronic, and the second time was Boston Scientific. Melani Dizon:

Okay, great. Susan.

Susan Scarlett:

I’ve had Parkinson’s diagnosis for seven years. I have had DBS for four months. I might win the prize for the most recent. I don’t know. Maybe not. But that’s the reason for the extra hair. Let’s see. I’m almost 72. What am I missing? Oh Boston Scientific, sorry.

Melani Dizon:

Okay. Yeah, great, thanks. Amber? Amber Hesford:

I started having symptoms around 32 or 33. I was diagnosed at 35 and had deep brain stimulation at 38. I am now 39, and the device is Medtronic’s.

Peter

Great. Thank you, Peter. Peter:

Hi, I’m Peter. I’m 51. I was diagnosed about 8 and a half years ago at age 43, which is around the time my symptoms started. And I had DBS six months ago. So, one of the new ones is also, in June 2022, and the device is Abbott.

Melani Dizon:

Okay, great. Doug. Doug Reid:

Hi everyone. I’m Doug Reid. I was diagnosed in 2010. I’ve been experiencing symptoms for at least a couple of years prior to that. I was 36 at the time. I’m 49 now and I had DBS just over three years ago. I have Boston Scientific, a rechargeable though.

Melani Dizon:

Okay, great. Steve.

Steve Hovey:

Hi, my name is Steve Hovey. I was diagnosed in 2007 and I also had symptoms a couple of years before that. I was 50 when I was diagnosed. I had the Boston Scientific installed exactly a year ago. So, I’m 65 now.

Melani Dizon:

Great. Thank you. Robynn. Robynn Moraites:

Robynn Moraites out of North Carolina. I was diagnosed in 2015, but I was misdiagnosed. My tremors started appearing in 2013. But once I understood the full constellation of symptoms, I was having my earliest symptoms back in like 2003. I’m currently 53, so back in my early to mid- thirties I was having symptoms. I had DBS in July of 2020, and I got the Boston Scientific device.

Melani Dizon:

Okay, great. All right. Now let’s go back to those days around your initial diagnosis, and I’d love to hear from some of you, anyone who wants to chime in about what your first line of treatment was. You know what happened when you got your diagnosis and then what did you do? Did you get on medication right away? Did you try and hold off? What happened? Anybody just let me know. Okay. Susan.

Susan Scarlett:

I completely forgot what you just asked me. Melani Dizon

What was your first line of treatment? Susan Scarlett:

Oh, the first line, I’m sorry was an immediate diagnosis and prescription for Sinemet and Azilect and it made, you know, from one day to the next, it just made a tremendous difference. And from then on, my doctor had in the back of her head and then started eventually saying to me, the fact that you responded the way you did and continued to do well with the medication is a good indicator for the surgery, which seemed quite I mean, I understood what she meant, but I felt so good because of the fact that the medication worked so well, I couldn’t imagine having the surgery. Why would I do that?

Melani Dizon:

Right. Right. Okay, Bart.

Bart Narter:

I had stayed off medication for a while, so I could participate in PPMI, the Parkinson’s Progressions Markers Initiative by the Fox Foundation, because they wanted people who hadn’t had drugs yet. And once I got on that program, I was given some pramipexole which is a MOAB inhibitor, I believe, and that helped enough, and I stayed on that for quite a while and then only then went to Sinemet after probably six or eight months to a year.

Melani Dizon:

Okay. All right. Amber and then Peter. Amber Hesford:

I immediately was put on medication, but during the process of me being diagnosed because it took years, I had already done the research, I was already convinced that I had Parkinson’s, and I knew that eventually, I was going to want to do DBS anyways. So, when it was brought up, there was no hesitation in doing that.

Melani Dizon:

Okay. So just really quickly, what was the time between the clinical diagnosis and DBS? Amber Hesford:

About two, two and a half years. Melani Dizon:

Okay, and you said you had done a lot of research before. So, was it just like, hey, no problem with brain surgery, I’m just I’m in like as soon as I’m allowed, I’m getting it. Basically.

Amber Hesford:

I mean, I have young children, so there was a risk, definitely. But they were also the reason why I had it if that makes any sense.

Melani Dizon:

Okay. Peter and then Steve. Peter:

Right. So, for me, getting on medication was never a question. Nobody said there was any sort of alternative to medication, I guess. My doctor said, here, take these pills, here’s a prescription, and I did. My symptoms were pretty mild at the beginning, but I would say the other major part of my treatment at the beginning was that I became athletic. I tried to become the most athletic person I’d ever been. I started commuting by bike and doing, you know, several miles a day. And I was probably in better shape at that point than I had been since my twenties. And I feel like that was an important contributor to my well-being for many years, even though, you know, I did start on probably pramipexole also, which I think is called what is it called in the United States? Mirapex? Yeah, I started on that. I think people know that that can become problematic after a while. But I did respond well to it. That and the exercise I think we’re really important in the early stages.

Melani Dizon:

Great. Steve. Steve Hovey:

Yeah, I just want to echo what Peter said. You know, when I, I think when you’re first diagnosed, it’s almost like they prescribe the Sinemet just to see if there’s a reaction to it. For me, there was really hardly any change at all. So, I stopped taking it. I then told my doctor that I wasn’t going to take it and that I probably didn’t take Sinemet for five years. And I just exercised like crazy.

Melani Dizon:

What were your predominant symptoms? Steve Hovey:

Well, my arm didn’t swing, and I had a little bit of a foot drag. And I was also at the time I was, ironically in the same year I get diagnosed with Parkinson’s, and I had my hip replaced. So, I blamed the foot drag and the lack of arm swing on the fact that my hip was so sore and once I got the hip replaced, it still was happening.

Melani Dizon:

That’s so crazy. I was just, Kristi LaMonica, she’s on our panel and I just had a conversation with her, it’s the exact same thing. She had the surgery. She did all the stuff with her hip, and she was like, this is still, it didn’t, that’s not doing anything. This can’t just be my hip, right?

Steve Hovey:

Right, right, right. You know, and so just the end of it is just that, what my neurologist told me is that, you know, as the Parkinson’s progresses, you’ll find that the medicine does make a difference. And he was right. I mean, you know, so eventually, I did start taking levodopa carbidopa, now I’m on the Azilect, I mean not Azilect, Rytary, and it works great.

Melani Dizon:

Great.

Steve Hovey:

That’s my story. Melani Dizon:

Yeah. Doug. Doug Reid:

Like Bart, after I was diagnosed I tried to stay off medications for a while to participate in clinical trials, but after about two years post-diagnosis, I felt the need for medication. I went on Mirapex and then Azilect and then it was probably about three years, maybe four years after diagnosis that I started taking carbidopa-levodopa, and after three years on that I became very dyskinetic.

And so that was one of my goals of DBS was to hopefully get off of carbidopa-levodopa which I have been able to do. Prior to having DBS, I wasn’t exercising. I was in a very deep depression and I’m sure that contributed to my dyskinesias, just the lack of exercise, and the lack of physical fitness. But now I exercise almost daily and I’m three years after DBS, I’m still off carbidopa-levodopa I just take two selegiline a day.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah. So curious about the volume of medication that people were taking before they ended up going to DBS. I know that you know, we talked to a lot of people in our other panel, they some of them had 35 pills a day, you know, the volume and the timing and the and the cost, like all of those things really sort of started adding up and leading them toward looking at DBS. But does anybody want to share their experience with that and Robynn?

Robynn Moraites:

Sure. I echo what many other people said. Medication and exercise were my primary first response. But what had happened for me with the medication is that I had to set a timer. I was so tremor dominant and my job is so visible, and I do so much public speaking that I had to set a timer so that my medication timing could overlap so that I would not have breakthrough tremors.

And I was, it wasn’t that my dosage had increased so much. It’s just I had this timer and I had to be sure to take my medication 30 minutes before the initial dose wore off. And it was like a slave to the medication. And it got to where for me I started getting dyskinetic and even with the same low dose of medicine, and I never knew how long my medicine would be effective. I give talks that are exactly one hour, and I could not count on my medication to last 60 minutes. I didn’t know if it would last 55 or 52 or 48. But, you know, and I started doing all kinds of things like twirling a pen in my hand and trying to disguise it.

But it was that it just got really unmanageable. And I too, like Amber, always knew I was going to be a candidate for DBS because my tremor was so dominant and so disruptive. And so, I’m the one who brought it up with my neurologist. She didn’t bring it up with me. I brought it up with her. And I thought he would tell me that I was, you know, way, way too young, way too early. And she said, no, you’re an ideal candidate.

Melani Dizon:

Oh sorry, Peter. And then Doug. Peter:

Right, so I started out on, you know, a very low dose of pramipexole, and my neurologist would up it like double it every six months or something like that. And eventually, the maximum dose of pramipexole, is I think three milligrams. I was on three milligrams extended-release. And anybody else who’s been there probably knows that you can get some very serious psychological problems from that, I mean, equivalent to mental illness and very destructive. We knew that that was coming eventually. I mean, we knew it was a possibility. But when it actually happens, it kind of sneaks up on you and it can be very scary. And so fortunately, you know, I mean, with the help of my family, my wife, I was able to get off that medication.

You know, the neurologist changed me from pramipexole and I was also on Azilect to levodopa carbidopa. I was very resistant to that because I was afraid of dyskinesia and I was afraid of ON- OFF and all that, which eventually dyskinesia didn’t become a problem, but ON-OFF did. So, I have always had rigidity-dominant Parkinson’s, and I do get tremors, but only when I’m nervous or cold. The public speaking usually wasn’t the problem before, now, you know, sometimes I shake a bit, I get a bit stiffer, and I do shake sometimes, less now with the DBS. But with the carbidopa-levodopa, eventually, I got up to the highest dose ever took was four tablets of 250 milligrams per tablet. So, I was up to 1000 milligrams a day.

Eventually, we sort of shaved some of that off by replacing it with a patch. The Neupro patch, what is it? I can’t remember the ingredient name, but you know, it’s a patch, transdermal patch, which is another one of these sort of dopamine agonists. And we were very wary of that one as well because when you get up even to the higher dosage of the patch as well, you can have some of the same sort of symptoms, psychological symptoms. At that time, fortunately, we knew what was going on and we would immediately called neurologist and say, no, you know, lower that dose. But all of that is very, very scary, and very, you know, can be very difficult for relationships. So, and then eventually, when I did get up into the higher doses of levodopa carbidopa what would happen was like Robynn, I knew that there were going to be OFF times, my OFF times became very severe, so I wasn’t ever like sort of stuck to the floor.

I’ve heard about that, you know, but I would go for a walk, and I knew that I needed to be back at a certain time, you know, because I was taking levodopa carbidopa every 4 hours and if I walked for more than, you know, an hour and a half, I would get stuck somewhere, and I’d have to call and get a ride because I just couldn’t move my feet. I mean, I could walk, but it was so hard and so painful that it was just exhausting. And that was eventually when I started thinking about surgery. Although my doctors had mentioned it from the beginning, you know, you might be a candidate for this later on. And I just never liked the idea of having somebody drill into my head. I don’t know about you guys. That was very scary for me. But when my symptoms became so severe that I couldn’t even walk across the room on the OFF times without falling over or leaning on something, then then I just wanted it so badly.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah. Yeah. Doug and then Amber. Doug Reid:

At the time I had DBS, I was heavily medicated. I took one Azilect a day, and then I took the extended-release, carbidopa-levodopa Rytary, I think I was on three of those every 4 hours, and I would take one Comtan with each one of those Rytary doses. If I did, I wouldn’t set an alarm to wake up in the middle of the night and take a dose, but if I woke up, I would take a dose. If I was lucky enough to sleep through the night, I would allow myself to sleep through the night.

But again, one of my goals of DBS was to try and get off as much medication as I could. Melani Dizon:

Amber.

Amber Hesford:

So, my medication is the same before and after surgery. I am on three doses of ropinirole a day and three half-tablets of carbidopa-levodopa. I have an extremely high sensitivity to it. I get very dyskinetic. I’m not on any medication right now because if I was, I am like a jerking mess, so I don’t take it if I have like something where I have to speak because it’s just very distracting to me. So, I’d rather deal with the tremors than the dyskinesia.

Melani Dizon:

So, exact amount. You went into DBS with the medication that you’ve normally had and the same now. And granted, it’s a very low dosage of both medications, but it hasn’t increased. Okay. Okay. Susan.

Susan Scarlett:

I did get switched to Rytary within a year and a half or so in. So, I have not taken very much medication at all. It was every 5 hours, and it was a higher dose. It was the 245. But since the surgery, that dose has come down. So, I’m still taking some carbidopa-levodopa and also the Azilect. But that’s it. One of the big surprises to me that no one talked about is, I suffer, if you will, a lot from nOH, you know, when you get lightheaded and dizzy and just, you know, going down on the floor to play with my dog when I get back up, I’m, you know, and that’s almost gone. And I thought, is that a result of the surgery? And recently learned that in fact, is a result of the fact that I had my medication lowered. I’m not taking quite as much because, yes, the Parkinson’s contributes to it, but the medication does, too.

Melani Dizon:

Right. Right.

Susan Scarlett:

And it’s a happy story for me. I’m going in the right direction. I, too, would love to be off of it. It was because of dyskinesia that I finally said, yes. I’m sorry. What does nOH stand for?

Melani Dizon:

Sorry? Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. Okay, Bart, so let’s go to you first on this whole you got diagnosed and that your initial DBS process, what happened with that and then tell us like how long you know, you waited for the next one. So was this something that your doctor initially reached out to you about, or you said, hey, like I’m interested in this.

Bart Narter:

I considered it inevitable that I would have DBS because I was diagnosed at age 50. And I you know, and they said I’m a great candidate because I’m relatively young and relatively strong. And it was all goodness until there was no choice back then, it was Medtronic or nothing. And so, I went with Medtronic and my neurologist has an M.D., Ph.D. in pharmacology.

So, when he recommends DBS, I know it’s got to be good because he believes in drugs since he’s in pharmacology. So, when he agreed to it, I just said, okay, let’s do it. And I went with a world-famous surgeon, Jamie Hendrickson, who’s well-known across the western United States

and even the world. And he did a great job in terms of nailing the target right on, which was the subthalamic nucleus, ST.

So, you have bilateral?

Bart Narter:

Bilateral. Yeah. And that all happened, the stimulator went in on the 3rd of February of 2016. We turned it on the 12th of February and the 19th of February it was red and puffy all around the stimulator. And I said it must be infected. So, I went to the ER, Dr, Henderson’s at Stanford, so I went to Stanford’s ER. We sent his intern to look after me and I had a white blood cell, kind of 12,000, which is best I can tell, is red light minimum. And they sent me home with the diagnosis of inflammation in the chest, which I thought was more a description of symptoms rather than diagnosis. And they tell me, I’m like in shock.

I was like, how could they send me home? And I was with two friends who acted as my second eyes and ears, and they agreed with me. So, then I called my neurologist and said, look, this is infected, and the surgeons are in denial. And that indeed was the case because they said, come back the next day. And that time, my white blood cell count was 17,600, which is flashing red light. And I could tell it was pretty serious by the way the residents’ eyes kind of dilated when they told me this, they saw this data and they scheduled surgery for the next morning to pull out the stimulator, which was indeed surrounded by pus. And they had something, it was just a staph infection, regular staph infection. They said that staph likes metal and it loves to follow metal up into the brain, which is where it was leading. And let’s see what date was that? They took the probes out, they took the stimulator out on the 21st and they took the brain probes out on the 24th when they did a little test in the ear, behind the ear, there’s a little junction box, and that tested positive as well. Wow. They had to pull out the brain probes as well.

Wow. It’s kind of scary. But there was a happy ending to this. There’s something called the microlesion effect. And what that does is it, the act of inserting and removing the probes causes little lesions in the brain which help with Parkinson’s. And it typically last three or four months and mine lasted three or four years. Why, nobody knows. Wow. Yeah, I took it, and it was kind of an adventure. I was very angry at the surgeon though and I years later submitted something to Stanford, that was, it got their attention. Big time.

Melani Dizon:

So, then you have this scary experience. You get the benefits from the lesions, and then you what prompts you to say, hey, let’s do this again?

Bart Narter:

Well, the little time it was in, it worked really well.

So, did you have time to actually get programmed like well? Like you were dialed in for a couple of days?

Bart Narter:

Yeah, I mean, so I’ve got all these dates here so I can answer your question exactly. Let’s see here. So, it went in on, they turned it on the 12th of February, and I had it until the 19th of February before I got the ER visit, my first visit ER visit. So, when they turned it on, it was my neurologist that turned it on. And he started programing it and it was working really well just right out of the right out of the gate. So, I did enjoy a few blissful days of DBS part one and I actually went to the same surgeon for part two, just because he’s so good, I just made sure my after-surgery care was managed by someone else and he was especially aware of these issues as well.

So, I’m sorry, I’m rambling now. You asked, how did I get DBS one and DBS two? Melani Dizon:

Yeah, just, you know, what were the symptoms that you were just like, this is not. I can’t. Bart Narter:

Well, again, I still considered it inevitable that I’d get it stuck in again. And what happened is I was on Rytary three times, four times a day at 245 milligrams. And that’s not quite the maximum or even, but we were starting to dance around the areas where I could get dyskinesia. And I just said, let’s do it again. In addition, I consider this kind of like a consumer electronics by now, I had choices, and I was leap frogging everybody, and I liked where the Boston Scientific product was because they had this rechargeable battery that I wouldn’t have to replace for 15 or 20 years. And given my experience with infections around the battery, I wanted something that you didn’t have to open up and replace every two years or three years.

Melani Dizon:

Right.

Bart Narter:

That was a winner for me. I came in there ready to go with Boston Scientific, and my surgeon, who initially was a big Medtronic’s fan, also was recommending Boston Scientific. So, we were in immediate agreement and off we went.

Melani Dizon:

Okay, so just by a show of hands, I just want to see where everyone was, how many people on the panel actually had a choice of what device to get? Okay, great. So, Amber and Robynn, you pretty much had your neurologist who worked with surgeons that were like, this is what we’re, this is what I use, this is what we’re using. Yeah. Okay. And so, what were some of the things for those of you who did have a choice, what were some of the things that you did to research and determine what the best one for you was going to be?

Steve Hovey:

My surgeon actually preferred Abbott and was pretty vocal about that. I mean, not that she, she said that she would work with either one, but she just I think when it came down to it, she had a really close working relationship with the Abbott rep. I, like Bart, said, I liked what Boston Scientific was offering and I just felt like technology-wise at that moment, they had the lead.

So, I went out to lunch with the Boston Scientific rep. Really got to know him, got to know the product and I was just really comfortable with that. So that’s the reason why.

Melani Dizon:

Okay, great. Peter. Peter:

Whose kitty cat is that?

Amber Hesford:

Mine.

Peter:

So, it was important to me to go to a surgeon who didn’t really have like a specific brand that they were married to. I wanted to have a choice. And in fact, it’s hard to know that ahead of time. It’s really hard to give a lot of information about what the surgeons are working with. I found that to be one of the most difficult parts of the process. But fortunately, the surgeon I went to, Dr. Gordon Baltic at Columbia University, he just, his people just handed me the brochures for all the brands and said, you decide, you know. I ultimately went with Abbott because for me it was important to be able to have remote programming and it was the only brand that had a remote programming option.

I live far from any sort of big city, and here where I live, there’s nobody who does any programming. So remote programming was absolutely essential to me. I had hoped to have a rechargeable device like Bart said, you know, that would last 15 years, and the Abbott device is not a rechargeable device. And I thought that that was a negative at first. But then the surgeon said, well, you know, actually it means that when you get a new device, you’re getting an update, you’re getting the latest technology. And I thought, okay, I can live with that, you know, as a tradeoff for the remote programing. And the Abbott team has been really great. I didn’t meet any reps before my surgery.

In fact, the first time that a rep was actually in the O.R., which was kind of an interesting way to meet someone, but they’ve been great in terms of follow up and we’ve had a good relationship.

Melani Dizon:

Great. That’s great. Doug and then Susan. Doug Reid:

I had a choice of which manufacturer to go with, but my neurosurgeon was recommending the Boston Scientific device. At the time, I think it was the latest and greatest tech. And again, this was three years ago. But the ability to recharge was also an attractive aspect for me. I also had an old college hall mate who worked for Boston Scientific in the DBS department, and so I talked with him and or emailed with him messaged with him and I was sold.

So, it was kind of an easy decision when the neurosurgeons are recommending the device and it had certain qualifications that appealed to me and met my interests or needs.

Melani Dizon:

Right. Susan? Susan Scarlett:

So, my Parkinson’s specialist, my MDS, is very involved in the surgery. She’s present and does everything, so she’s very familiar and she works with all three systems. She brought all three batteries, you know, into the examining room. You know, on one of my pre surgical visits and so we held them and looked at them. And talked about it.

I had had a bilateral mastectomy one year before, and so there was a lot of tissue that wasn’t there. And so, there’s, I was just really lean, and the Boston Scientific was the smallest. And so that was appealing to me for that reason, and it appealed to her for that reason as well. And because it can take two leads. She also only she believes very strongly in only doing one side at a time of, you know, the operation, but that if I need to have a second one the Boston Scientific has can accommodate two leads. The second one’s in there waiting to get attached if it ever needs to be. Right. Did I hit all the? Yeah.

Melani Dizon:

You had all the all the choices. You know, it’s interesting. And I love it when people do have the choices, a lot of people don’t have the choice. And you just you know, as long as you trust your MDS and surgeon, that’s usually okay. Right. But it is nice to be able to do some research and have that choice. Bart.

Bart Narter:

Yeah, this would be the case of trust, but verify. You know, my neurosurgeon lost a lot of status with me. I did a serious amount of research on this. So, I was going to do a research study at Stanford, and that would have led to a technology cul-de-sac because the only people who could get these special units from Medtronic were in research studies. And I didn’t want to be stuck with something that was so far out. And Boston Scientific had a lot of good features about it. For example, the multiple endpoints, it has many more endpoints than the Medtronic at the time. Again, you can only do this and take a snapshot in time because now they’re adding features when you have three competitors. And again, when I came to the conclusion the Boston Scientific was best and so did my neurosurgeon, we it was all just a giant love fest.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah, So, let’s, ok let’s do this. Raise your hand if the process between you considering DBS through getting approval was fairly simple, easy process.

Bart Narter:

I mean, it was very involved. Melani Dizon:

Right, but it wasn’t like –

Bart Narter:

But I didn’t hit any roadblocks, but I had to go for neuro-psych testing. I mean, there was a lot that had to happen.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah. Okay. Peter, did you have a different experience? Peter:

Yeah. For me, finding choosing a surgeon was a major ordeal. And I don’t know if this is true for everyone. I guess I’m in the fortunate situation that my insurance would cover me in many different parts of the country, even the world. So, I was kind of spoiled for choices. But on the other hand, how do you choose a surgeon? I mean, I talked to friends who have a lot of experience as surgeons themselves, and, you know, there’s not really sort of clear answer. And I read New York Times articles and I did a lot of research, and they say, ask this question. Ask that question. But first of all, if you’re just calling or emailing, you can’t get answers. And a lot of this information isn’t published. So finally, you know, I had to base my choice on, okay, who has the most experience? And I ended up finding again, my surgeon, Dr. Gordon. Gordon Baltuch of Columbia. He’s done, I think, more DBS than anybody else. And so, for me, that was a good start.

Melani Dizon:

Did you have an MDS at the time, a specialist? Peter:

Yes, but I don’t live in the U.S., so my specialist didn’t know the surgeons in the U.S., and I was going to the U.S. for the surgery, and they agreed to help me sort of vet them. But that didn’t really work out. So, I really felt like I was on my own. And ultimately, I think I made a good, I was very happy with my choice.

I was super, super happy with Dr. Baltuch and how everything went. His you know, his degree of experience meant that not only has he done a lot of these, but also he’s developed a different approach. And one of the things I wish I knew, you know, at the outset was like that there are so many different approaches to the same, you know, umbrella of DBS surgery, like one surgery, two surgeries, three surgeries, you know, one side, two sides, which area are they going to target, which, you know, which device you’re going to use may affect how things go.

So, all of these things for me were just like a big black box. And I spent a lot of time worrying about it and doing research. And I think, you know, I guess ultimately it paid off. I think ultimately, I was very, very happy with where I went. I don’t know how much of it was just luck, you know? I mean, you know, they don’t have a lot of the hospitals don’t publish how many times a given surgeon has done this surgery and you don’t know if they’ve done it a dozen times or, you know, 500 times or 600 times or more like Dr. Baltuch. Yes.

Melani Dizon: Um, yeah.

Robynn Moraites:

I want to say that I think Peter brings up such an interesting point and for the listening audience. So, I was comfortable with my local team, but I knew what kinds of questions to ask. So, I asked my, my doctor is the head of the DBS program. She’s a movement disorder specialist. She’s not the neurosurgeon, but she pairs with a neurosurgeon. And I asked things like, how many of these surgeries have you done? What has been your complication rate? Have you had any deaths? You know, things like that. And I was comfortable with their answers. They hadn’t done more than anyone in the U.S. but at the time I had my surgery, they had done more than 300 of these surgeries and they had a less than 1% complication rate, which is lower than the national average. And they had had no deaths. So, you know, I knew, I think it’s important to tell folks what kinds of questions to be asking.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah.

Peter:

Can I respond to Robynn just really quickly about that point that she was making. So, I think that the which questions to ask your surgeon are super important. And for me, you know, percentages are kind of difficult to process. So, I wanted to know how often my surgeon does the surgery and then given how often they do it, like how many of these complications have they had in the past five years, let’s say?

So, if my surgeon was doing, you know, one DBS every Thursday, you know, every week. So then how often have they had someone stroke out in the past five years or how many times have they had a brain bleed in the past five years? And if the answer was none, I was very happy. And also, I think in my family, a number of people have had so serious surgeries and we’ve already come to the conclusion, you know, before my DBS that your local may not be the best person for a given surgery. I mean, the local person might be the best person for follow up. But, you know, we always want to go to somebody who does it more often. And also, I had the good fortune of speaking to one of the neuroscientists who helped develop one of the devices, not the Abbott device, which is another device.

And what he told me was that just as important as the relationship you develop with the surgeon, you know, for the surgery, the long-term relationship you can have is with the neurologist programmer, and you need to make sure that the surgeon works with somebody who has a lot of experience. So, you know, again, the neurologist programmer I work with at Columbia has been doing this for more than a dozen years and has a lot of experience and that is the person that I’m going to be in contact with for, you know, a really long time.

Melani Dizon: Right.

Robynn Moraites:

It’s so imperative. I don’t think people realize and we’ll get into it a little bit more. But the

programming is where the rubber hits the road, for sure, that’s all where the money is. Melani Dizon:

Yeah. We’re getting we’re going to get there next. Susan, then Amber and then Steve. Susan Scarlett:

So, I’m feeling really lucky here. I told you guys my MDS is in the surgery. She actually gave me all the information that you, Robynn, were asking the questions. You know, she recommended the surgeon. They had done 700 of them together, you know, so I got all the statistics about, you know, infection and everything ahead of time. And that’s what I would have said. The one big question that my husband and I had was one side versus two, because my MDS simply would not sanction doing two. She feels that strongly about it. So, I had the occasion, my niece is an MDS as well. So, I talked to a surgeon that she works with via Zoom. And so, I had I interviewed a second surgeon with respect to that question. Why? And we may get into that. We may not. And then the other thing I wanted to tell you is the Boston Scientific people were also in my MDS’s office before the surgery showing me the equipment and stuff. So, I feel really well cared for here, listening to everyone else’s stories. Definitely. Amber.

Amber Hesford:

I’m about to make you feel better Susan. So, I the process for me happened so quickly from the time that my neurologist told me that I would be a good candidate to the time I had the surgery was about two months.

Melani Dizon:

Wow. Wow. How did your brain process that? Amber Hesford:

Still processing it now. So, I didn’t even think to do the research to find a different surgeon. I went with the surgeon that was recommended by my neurologist. We don’t have an MDS anywhere locally, so I don’t have one. So, I didn’t know to, I asked how many people have died during their surgeries. That was the one question I asked. And since there were no deaths, I was like, okay, I guess we’re good to go. But until I have gotten more involved in the community and been involved in more panels, do I hear some of the things that I’m like, wow, you know, I really lucked out. I have a very good relationship with the Medtronic’s rep. As a matter of fact, she recommended me for ambassador for Medtronic.

Susan Scarlett

So, I do field calls from people that are considering getting DBS surgery. I don’t know why because I’m very honest about my experience. So, it baffles me why she would have offered me up for that. But yeah, hearing some of your experiences is definitely different than mine.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah, you got lucky. Steve and then Doug and then Bart. Steve Hovey:

Yeah, you guys mentioned it, but it’s the programmer is also so important, and I know I know of at least three people who were not having a really good experience after their DBS, found somebody else to do the programming and it’s made a world of difference. I mean, the one gentleman that I’m in contact with frequently, I could hardly understand him speaking. And I felt terrible because I was always going, What? What? Why? You know? And then, like, the next time we met, it was completely different. So, it does make a big difference in who does the programming.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah. We’ll def, we’ll get to programming after Bart. Doug? Doug Reid:

Just in hindsight, when I look back on the process and how everything flowed, I feel very blessed, and I was very fortunate. Everything just seemed to fall into place. I guess what started the process. I watched a Davis Phinney Foundation webinar with the neurosurgeon presenting on DBS and I live only about 15 minutes from the Foundation’s office. The neurosurgeon practices in the area.

I have a background in health care and medical technology. Everything that she said about the way she did the surgeries, the procedures, the technology, it all made sense to me. And it just kind of everything fell in line. And as a result, I jokingly consider myself the poster child for positive outcomes of DBS.

Melani Dizon: Is this Kara? Doug Reid: Yeah.

Yeah. Kara Beasley, she’s our on our board, a really great surgeon in this area. So, yeah, I’m glad you had that experience, Doug.

Doug Reid:

Yeah, I after I watched the webinar, I checked out her CV and it was amazing. And when I went in for the initial consultation with her, she said DBS is her favorite procedure to perform because the outcomes are usually so positive. And she said it can be life-changing for you. And it has been.

Melani Dizon:

And so quickly. Bart. Bart Narter:

Yes, I would also consider myself very lucky because I live in the San Francisco Bay area where there are gobs of surgeons, lots of research happens about around Parkinson’s and my movement disorder specialist actually programs both Medtronic and Boston Scientific. And he is an amazing guy. He will spend an hour with you if that’s what he needs to do to get you dialed in right. That’s so good. And he is not from the US, you know, the People’s Republic of China. And he says, I just don’t understand the capitalist medical system because he wants to make me good. He doesn’t care how long it takes whereas capitalist medical system is all about how many patients can you see per hour.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah, and something with programing that just doesn’t work for so many people. So, let’s do a raise of hands. How many people had a good result that lasted, you know, a pretty long time with their initial programming? Wow. Okay. Holy moly. We’re talking second round, Bart. Okay. So, everybody. So, okay, in fairness, let’s speak for the people who that’s not the case. Like, as you said, Steve, we have lots of people in our community who are where excited, got DBS and they are still struggling. They have not, it’s not programmed well, I don’t know, is it where the leads, a lot of it is saying, hey, it’s the surgeon where they, the precision in placing those leads is critical. But they’re also still just not getting programmed well, and that is absolutely devastating for them. Bart?

Bart Narter:

Yeah. I mean my I had to go back for three or four rounds before it was totally dialed in. Right. Number one thing and the number two thing I can’t remember anymore.

Okay. Yeah. So, I mean, that’s an important thing for people to know. It’s not a one-and-done. You go a couple of times there, things change and turn this up, turn this part down. I’m getting this now. I don’t want that now. And it’s really important to have a good programmer who’s open to having those conversations and is willing to see you when you need to be seen. Bart.

Bart Narter:

I remembered what it was now. Okay. When I searched into where I should go with Medtronic or Boston Scientific, somebody said that the Boston Scientific was harder to program because there are too many, too many dials you can turn as a programmer, you know, because you can you have like 32 end points or something like that. And to get every endpoint right is hard.

Whereas with nearly all four endpoints, it’s much easier to get it dialed in as much as you can. I don’t know. You have to decide as well.

Melani Dizon:

Peter and then Robynn.

Peter:

So, one of the things I didn’t understand at the beginning is why is it important that these devices have these multiple endpoints is often because it’s the surgeon doesn’t get the target quite on target. And so, then they have to direct the signals. And I think the first thing is like maybe a question people can ask you’re the patient, the physician, or they can ask the reps separately, privately, is how often does this surgeon get the target? So, after my surgery, when I started having conversations with the Abbott rep, you know, this Abbott rep that I was talking to works with like eight surgeons and says, you know, the surgeon you chose is great because he gets it on target more than anybody else. And that makes a really, really big difference.

And in fact, I don’t know, like if we’re if you want to talk about the actual surgery procedure later on, then we can talk about that. But yeah, I think the programming is definitely an ongoing thing and people need to be patient with it. And if you’re the kind of person, like my dad is the kind of patient where the doctor says, take this and, you know, he takes that, but he doesn’t ask questions. And I think you need to be the kind of patient who asks questions and talks a lot and is willing to kind of complain to your doctor and let them know what’s going on and communicate well in order to get this to work, because it’s definitely a back and forth.

Melani Dizon: Robynn, then Susan. Robynn:

Yeah. So, with the programming, Mel I don’t think I appreciated before I had the surgery, I kind of had this idea that it was a magic bullet and that you just turn on the system and it’s all magical and everything just vanished is and I did not understand that there could be really significant alternative manifestations of things. And I know a couple of people who just upon having the wire inserted, not even turning it on their dyskinesia, vanished, just having wire inserted before anything was even active.

So that’s what I was expecting. And I showed up the complete reverse. I don’t take any medication at all now, I’m medication free because even the tiniest bit of medication makes me dyskinetic. So, I’ve been medication free since 2020. But the other thing that happened, and I think it’s pretty significant and people should know about this as an option, is that in order to control my tremor, because my tremor was so dominant and so pronounced, we started having to turn the system up too high.

And then I was feeling woozy in the head and my speech was getting slurred. And then, you know, my programmer is the head of the DBS system. She’s a movement disorder specialist so she’s pretty good. And she was dialing it in and paging end points. But then finally, back in March of this year, I said, look, this isn’t working. I mean, it was, but it wasn’t. And I said, you know, here’s what’s going on. And she said, I want to try something with you. It’s something that’s being talked about in the conferences right now. I was the first patient she ever tried it with. All of these systems operate typically on a negative polarity, and I don’t know if all systems can do this, but the Boston Scientific system can switch to a positive polarity.

And she switched to the positive polarity. And now I’m having 99% total control with no side effects whatsoever. And this is like a new thing. So, it’s just I was really disappointed when I first finished my surgery, and I was so wildly dyskinetic when we turned the system on. I mean, I had to almost turn the system off and detox from all my meds and then turn it back on so that I could function. So, it’s just not a magic bullet for people and I know several people who’ve had really dismal outcomes and they’re not on the panel today. They chose not to be part of the panel, but I think people should know that it isn’t a magic bullet.

Melani Dizon:

Absolutely. Susan. Susan Scarlett:

I want to follow up on I think it was Bart’s comment about the 32, you know, like endpoints. My impression of that and I’m interested to know if I’m wrong or mistaken somehow. But my impression is there’s there are four points and each one has like eight areas of directionality and power that can be emitted. And timing pulsing that can be emitted. But my impression is my doctors only use two of those four points to determine which, how much of all those things

I needed, the directionality, you know, at my toes, but not my ankle, that kind of thing. So, do does anybody know?

Robynn Moraites:

No, they don’t turn them all on, but they have those choices. So, they’re not all on at the same time, but they have more choices with that instrument.

Susan Scarlett:

That’s what I thought too. Yeah. Yeah. And my programmer is my MDS. So again, she’s a tough character. I know a lot of people who’ve quit her practice because she has such a powerful personality, and this is an amazing experience for me. I really felt blessed, but I really feel blessed by comparison with some of the experiences, even with her strong personality. In terms of my programming, my system was fully implanted and then a week later I went in for the initial programming. And I remember after that meeting, I mean, I had a low dose of electricity going from my generator into my brain. And I remember telling my friends and family the energy, the electricity that the generator produces. It’s almost like medicine.

If I dial it up to high, I get dyskinetic like I’m on too much carbidopa-levodopa. Or if I dial down too low, I’ll start tremoring. And it took a while through various programming sessions to for my body to get used to the energy if that makes sense. And so, I would go in for a programming session and they would up the threshold of availability of electricity for me to control with my with my remote-control unit. And over time it probably took about a year or so to get to the level I’m at now. And now I go in for programming sessions every six months and it seems like they’re trying to fine tune things that may or may not work. I don’t swing my arms a lot when I walk, so they’ve tried to adjust the electricity to adjust the pulse width from the energy to control things.

But I found that I recently went in just two weeks ago for a programming session and I told my movement disorder specialist, he does the programming for me, I told him that I was jerking almost like I’ve had people ask me if I have Tourette’s and, no it’s Parkinson’s. And he tried to create a program to stop me from twitching. But I found that I was tremoring more. And so, I switched back. And long story short, I’m at the same level of energy for both the right and left sides of my brain as I’ve been at for about two years now, so all things considered, my programming is pretty stable. But it took about a year to get things very fine-tuned to work. But again, after that initial programming session, I walked out of my neurosurgeon’s office and just felt like I was on cloud nine like my life had been changed.

Melani Dizon: Peter.

Peter:

Well, while we’re on the topic of programming, I just wanted to mention that one of my goals was getting off the medication, or at least as much medication as possible. And, you know, it’s not instant. I’m six months out now and we’ve been going very, very gradually. So, we’ve reduced one of my medications by about two-thirds, and we’ll probably eliminate that one over time. But I kind of thought it would just be like, you know, we switch it on and ok you don’t need that much medication after like a month or something, you know? But no, no, no, no. It’s this is going to go on for at least a year or so, maybe more, before we get to the point where my medication reaches the low that it can be, which my surgeons told me from the beginning it might not be zero. 40 – 50% reduction was their target, their sort of average target for the typical patient. And I’m okay with that. I just, you know, like at least the ONs and OFFs have become much more stable.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah, the programming. Yeah. Bart Narter:

Two things about what Peter said. One is that you only get tons of medicine reduction if you go for the STN target. There are two targets, STN target, and GPI and there are advantages and disadvantages to both. And the advantage of the GPI is it’s an easier target to get and the advantage of the STN is it enables you to cut your meds a lot more.

Melani Dizon:

So, we don’t have time for everybody to answer. But I would love to hear from two people about anything you think is important for people to know regarding the surgery itself, what is something that surprised you? You didn’t know going in and you just really want people to know? Doug?

Doug Reid:

I had the impression that I would be knocked out cold at the start of the procedure. They’d drill into my skull and then wake me up to go through the Parkinson’s tests and for then to get feedback from me if I was feeling facial pulling and tension. And it was kind of a shock when I was conscious throughout the entire procedure, I was sedated, but hearing the sound of the bore going, drilling through my skull was a shocking sound and something that after the first side of my brain was done, I thought, well, I can go through it again, but I hope I never have to hear that a third time. Yeah.

Melani Dizon:

Real quick. I forgot to ask. Anybody do it asleep? You didn’t Steve. Oh, Bart and Peter. Okay. Bart Narter:

So, but they, they woke me up to test me, you know. Melani Dizon:

Okay. Yeah. Yeah.

Bart Narter:

But thankfully I slept through the drilling part. Melani Dizon:

Oh, okay. Okay. Yeah, yeah. Sometimes they do full asleep at this point. And is that what you had, fully asleep, Peter? Okay.

Peter:

I did.

Melani Dizon:

Let’s talk a little bit about that.

Peter:

Well, I was trying to mentally steal myself for, you know, having to be awake and hear the boring drill sound going through my skull and all that. But Dr. Baltuch said, look, you know, I’ve been doing more and more of these fully asleep. He does an MRI before the surgery and a CT scan, you know, in the O.R., and I believe you can you know, combines the two images into a very high-resolution scan. And he said, statistically, I’m not seeing any better results from people being awake. And I said, look, I’m willing to be awake, you know if that’ll be better. And he said, okay, thanks for letting me know. But my experience was, okay, we’re going to give you some medicine so you can sleep now, okay, take a deep breath, wake up. And that was it.

Melani Dizon:

Wow. Yeah. Okay. So, he was just he was convinced this was the best route for you. Did anybody have did anybody’s doctor say, hey, do you want to do the asleep or awake? Bart?

Bart Narter:

Well, no, but what I had is the first time I had awake but I was knocked out for the drilling bit, so I didn’t hear any of that. He woke me up to do the test. The second time I was totally asleep because he already had nailed the target in his system. And plus, he didn’t want to hear me say things like make sure you wash your hands before you do this. So, my second time was totally knocked out.

Melani Dizon:

Ok, Robynn. Both wonderful. Robynn Moraites:

Yeah, I was, mine was a two-part series where I got the fiducials drilled into my head in an outpatient procedure where I was fully awake, and I ended up throwing up from that procedure because of the sound of the drilling, not on the doctor’s shoes but in the garbage can. I said this must happen a lot, he said, no, actually it doesn’t. So that was nice. But my surgery took an extra-long time. They woke me up and I was out when they did whatever they did to get me locked into the system. And then they woke me up. And when they woke me up, I said to my neurologist, I said, everybody said, you’re so brave, you’re so courageous.

And I didn’t feel like that until right now. Most of these surgeries last about an hour, an hour, and a half to two and a half hours. Mine lasted 4 hours and 45 minutes because they couldn’t get it on one of the sides. I did bilateral under the same procedure because I never want to do this again. And so, my doctor, even though I was having no symptoms on my left-hand side, and I knew that one day I would, and I didn’t ever want to do this again, so they were having trouble getting the reading on one of the sides and we had to go up and down a second time to do it.

But I remember being awake and when they hit this certain millimeter measurement at a certain wattage and my tremor just vanished and, I just got this huge smile on my face. I do want to say one other thing, that unexpected thing that happened. I had an immunological, not an infection, but an immunological response to the battery implant. There which means it looked like I had hives for 4 to 6 weeks after the chest implant surgery. And my doctors were like, no, no, it’s the anesthesia working its way out of your body. Anyway, they didn’t know.

They didn’t have a clue. They never experienced it before. And it’s listed as the number one side effect of the stimulator packaging an immunological response. And so just things can happen that you’re just not expecting that you know, I’ve never come across anybody else who had that response, but I did. So, I just want people to know there’s all kinds of crazy things that can happen.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah, that’s great. That’s a great point. All right. We’re going to start wrapping up, but I would love to know if you have something to share. Number one, the thing that you are able to do

after your DBS that you’re so grateful for or and the second thing is anything that you wish you knew before or just want to make sure people know about the entire experience. Anybody is free to answer that. Amber?

Amber Hesford:

I was not prepared for the equipment in my body, so the first time that I lay down flat after the surgery, because initially they have you sleep sitting up, so blood doesn’t pool, and you don’t get black eyes. The first time I lay down, when I woke up, it felt like the wires got bunched up in my neck and I couldn’t extend my neck and it freaked me out.

I was like, oh my God, I broke it already. Like first week out, I don’t know what they’re going to do. You just have to rub it out. But I was not prepared for what it was going to feel like to have equipment like the wires in my head. So, I still feel pressure when I lay down on that side, sometimes more pressure than others. But that was something that I had not even thought about, obviously, because it went by so fast. So, I didn’t have time to think about all those things. So that’s definitely one of them.

Melani Dizon:

Okay. Peter? Peter:

So just in terms of how the surgery has changed my life, I mean, when I first went in to see the neurosurgeon, I was using a walker because I couldn’t really just you know I couldn’t walk on my own anymore without falling over. I had originally started using some like walking sticks, you know, these kind of alpine walking sticks. But I couldn’t even move them properly. And, you know, I didn’t even know how I was going to when I was flying across the country, whether I could do it alone or not. And now I just I don’t need a walker, I don’t need sticks. I’m just walking, and I can walk as long as I want, as much as I want. Sometimes I have most of the time I have no OFF at all. And so, for me, it just really fulfilled my goals. Now, there were things I experienced, you know, like everybody had problems, I’m sure. I had some problems. I was vomiting like crazy for the first 24 hours after the surgery. I mean, and I said, does this happen a lot?

And they say, no, I was vomiting of bile. It was just awful. And it might be because the surgery was a long one. It was like an eight plus hour surgery because they do both sides and the generator all at the same time. And one of the things I wish I had known at the beginning was that that was an option because, I mean, I would have chosen to do it all at once. I didn’t want to have multiple surgeries and multiple exposures in the hospital, especially during COVID and everything. But, you know, even just being exposed in that way. So, I’m glad that that ended up

being a potential option for me. And yeah, it’s just been so life-changing. I always describe it as life-changing.

Melani Dizon:

That’s great. Thank you. Steve and then Robynn. Steve Hovey

Yeah, yeah. It’s like my wife has to remind me of what it was like a year ago. I would wake up in the morning and I would need a cane to go downstairs, and I would freeze. There were times that I would, I would shuffle, freeze. I fell a couple times. And, you know, you kind of forget the bad stuff and I’m reminded of that. Now that never happens. And I do take, my medicine is like a fraction of what it was before. I sometimes I wonder if I even need it at all. But I do take a little bit of it. No more shuffling, no more rigidity. The thing that really that means so much to me is I’m an active person. I love to cycle. I love to work out. I love to hike and I’m able to do that again. Before the surgery, I would get off my bike and I would shuffle. I was like a mummy just walking from the driveway to the garage to put the bike away and all that’s gone. Now that’s the good part and it hurts. There’s, you know, at least it hurt me. The other part of it too, the surgery itself I’m talking about, there are some unintentional side effects that you may not be aware of and I’m sure it can be different for everybody. But and maybe, this is a programming thing that I need to talk about, but my voice gets very hoarse and very weak.

I have to be careful when I eat, I’m choking more than before surgery and my handwriting is gone from poor to just you can’t even read it. So, I’ve got to work on that. But on the other hand, I’m sleeping too, so and that wasn’t, that was not anticipated that it would really have an effect on that. Yeah. So, but overall, it has been a home, it’s been a grand slam. It’s been wonderful.

Melani Dizon:

So. Thanks Steve, Robynn. Robynn Moraites:

Like Steve, I want to say that there can be some unintended consequences. First of all, I live a totally normal life. I followed more the European route, which is get surgery early and have the best quality of life for as long as possible. There’s been a reversal in the thinking about how to treat Parkinson’s over the last 10 to 15 years. They used to say, put off medication as long as possible till the last possible moment, then take medication and put off surgery, as long as possible. That’s completely flipped. They say now, do everything early, have the best quality of life. So that’s the path that I followed. But I was doing triathlons and after I got DBS, another side effect that can happen is you lose your ability to swim.

And there have been drownings in Australia. There’s research, you can Google it. There have been drownings of people who were swimmers who jumped into the deep end of a pool, and they drowned because they couldn’t swim. I was training for a triathlon, and I was like, what is going on? And I haven’t tried to swim laps, I mean, I don’t drown, but I cannot do a coordinated freestyle stroke. If I get a good stroke going with my arms, I can’t kick with my legs. If I get a good kick going with my legs, I can’t go with my arms.

Melani Dizon:

And so, wow that is not something I have ever heard. Robynn Moraites:

Yeah, my doctors were like, we’ve never heard of this. I’m like, Google it. It’s there. You can even watch. You can even watch the YouTube videos.

Melani Dizon:

What Steve? Steve Hovey:

It happens to me. And I never knew that I never knew. I mean, the lower part of my body just sinks, and I love to swim. And now, anytime I jump in the lake, I’ve got to have a life jacket with me. Well, and so I haven’t tried swimming laps since I’ve had this positive polarity programming. I’ve been to the beach, and I told my partner, I’m like, I think I’m swimming like I used to swim. I mean, I’m from Miami, Florida, so I’m a swimmer and I need to try and like discipline swim laps and see if this positive polarity has restored my ability to swim.

Melani Dizon:

So interesting. Susan and then, Doug. Susan Scarlett:

I think your question initially was what are we the happiest about that’s changed? And I would say no more dyskinesia, no more. I mean, it’s just not there, and it’s just the best. And the nOH as I said before, the lightheadedness was a powerful, it affected all my exercise, everything. And the fact that that’s diminished some is significant. In terms of the surprise part of the question and I think I heard a couple of people say that there are some tiny little new things that they didn’t have before, and I have experienced that. And I hope that this, I’m making the right decision.

And I think when I was talking, listening to Doug, he made me think, yeah, you probably have. On the whole, I’m you know, I never had my shoulder, you know, kind of pull back like that. But it’s so quick and brief and minor that I almost feel like I don’t want to ever adjust it because it’s gone. It’s new and different. So, you don’t want to mess with something else that’s going well? Yes. You know, on the whole, I forget I have Parkinson’s. Most people don’t know I have Parkinson’s. That’s an absolute blessing. And then I just wanted to say, my friends who had this surgery said to me, you’re going to get your life back. And that was such a powerful thing to hear. And I just wanted to share that.

Melani Dizon:

Yeah, thanks. Doug? Doug Reid:

For me, prior to getting DBS, when I would speak in public or just speak around my friends and family, I would get this more dyskinetic and I worked in sales. I would have to make sales presentations and I would be very dyskinetic and then I would start to sweat, and I just felt out of control. And so, I feel like I can talk once again, whereas before I would keep my mouth shut oftentimes. And the ability to fall asleep is greatly better than it had been before. So just those two things have been life-changing in and of themselves. I mean, not wiggling all the time. I can work out, I can sleep. Yeah, and I can sleep pretty great.

Melani Dizon:

Well, thank you all so much for being on this panel. I think it’s going to be really helpful for our community. So many people are asking us, what is it like? What happens when you get DBS? And we wanted to give a lot of different perspectives and a lot of different stories. So, I really appreciate you being here. And we will be sharing more resources about DBS soon. If you have any questions about DBS, you can reach out to me at blog@dpf.org and we will see you online. Thank you so much, everybody.

Want to Learn More about Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)?

You can find a wealth of resources about DBS here.