Parkinson’s is officially classified as a movement disorder because it involves damage to the areas of the brain, nerves and muscles that influence the speed, quality, fluency and ease of movement. While the effects of Parkinson’s on movement are often the most visible symptoms, like tremor, non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, like emotional and cognitive challenges, can sometimes have an even greater effect on your quality of life.

Parkinson’s is officially classified as a movement disorder because it involves damage to the areas of the brain, nerves and muscles that influence the speed, quality, fluency and ease of movement. While the effects of Parkinson’s on movement are often the most visible symptoms, like tremor, non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, like emotional and cognitive challenges, can sometimes have an even greater effect on your quality of life.

The effects of Parkinson’s not related to movement are called non-motor symptoms. Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s may actually outnumber motor symptoms and can appear years before motor symptoms.

In this article, we will help you identify and learn about the various non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s so you can take the first steps to living well.

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s are effects not related to movement.

There is a wide variety of possible non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s, ranging from physiological effects like trouble swallowing, pain and fatigue, to mental and emotional impacts, such as mood changes, cognitive challenges and anxiety. Just as Parkinson’s affects everyone differently, the type, frequency and severity of non-motor symptoms each person experiences vary. Remember, just because something is listed as a non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s does not mean you will experience it.

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s have traditionally been harder to identify because they are not as obvious as many of the physical symptoms. However, non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s often begin before the more visible physical symptoms. These are called “pre-motor symptoms.” Symptoms such as loss of smell, depression and constipation may appear years before your actual diagnosis.

Non-motor symptoms also tend to cause more stress and frustration in everyday life than the motor symptoms of Parkinson’s. Recognizing and discovering how you can best manage your non-motor symptoms are critical for learning to live well with Parkinson’s.

It’s a lot harder to explain the Parkinson’s that people don’t see. —Paul

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s can include:

- Cognitive challenges

- Memory problems

- Feeling tongue-tied

- Fatigue

- Sleep problems

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Apathy

- Loss of smell

- Numbness or tingling

- Pain

Some of the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s are connected to the effects Parkinson’s has on the autonomic nervous system, which controls functions your body “automatically” does, like blood pressure, sweating, digestion and heart rate.

Non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s that can be caused by changes and impairment to the autonomic nervous system include:

- Constipation

- Frequent need to urinate that can develop into incontinence

- Lightheadedness, especially when getting up in the morning or rising from a chair or couch

- Sexual dysfunction, especially erectile dysfunction

- Excess salivation (drooling)

- Excessive perspiration

While most popular Parkinson’s medications do not treat non-motor symptoms, some do find specific medications can be effective for certain non-motor symptoms. There are also several lifestyle changes that can help manage and even reduce non-motor symptoms, such as exercising regularly, reducing stress and getting more sleep.

Many non-motor symptoms may seem unrelated to Parkinson’s or even an intentional choice on the part of the person living with Parkinson’s, like apathy or cognitive challenges. Since non-motor symptoms can have such a profound impact on how you and your family live, it is important to mention what you are experiencing with your healthcare provider. Your healthcare provider can then discuss various medical and lifestyle management strategies and refer you to the appropriate specialist(s) when helpful.

Watch to learn more about non-motor symptoms

Although changes in cognition or thinking abilities can happen at any time, they typically tend to come as we age. Statistics show that as many as 95% of people with Parkinson’s will experience some kind of cognitive change throughout the course of their time with Parkinson’s, ranging from very mild to acute.

One way Parkinson’s can affect your mind is called bradyphrenia, meaning “slow brain.” A common complaint among people with Parkinson’s and their families, bradyphrenia often shows up as a slowing of processing speed in the brain and trouble switching from one task to another.

While everyone experiences subtle changes and declines in how they think and process with age, people with Parkinson’s who have more trouble with cognition than what is considered normal for their age have mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Typically, three primary areas of cognition are affected:

- Executive functioning: including multitasking, reasoning, problem-solving, concentration and complex planning.

- Language: including difficulty finding the right word in your mind or feeling tongue-tied.

- Memory: trouble retrieving memories that have already been encoded. This is different than Alzheimer’s, where memories are not able to be encoded.

In many situations, these challenges do not significantly impact daily life. For some people living with Parkinson’s, these changes will never progress beyond mild cognitive impairment. Others experience a very slow cognitive decline over time.

If cognitive challenges start to have a significant impact on quality of life, such as making it difficult to drive or consistently forgetting important things like where you parked, if you paid a bill or even what you ate, mild cognitive impairment may be better described as dementia. Dementia brings up a lot of fear and can be difficult to discuss, even with your physician. However, physicians can perform objective tests to measure your thinking and memory to help identify when and cognitive impairment should be addressed. Keep in mind that the progression of dementia that can come for some people in the later stages of Parkinson’s can be influenced when caught early and managed proactively.

If you or your care partner and family members notice changes in your cognition, have frequent conversations with your physician. There can be several different influences on problems you are having with thinking, processing and memory. As Dr. Benzi Kluger of the University of Colorado – Denver describes in the video below, many of these cognitive challenges may be treatable or even reversible.

Watch to learn more about cognition

What you can do right now to live well

An evaluation by a neuropsychologist, a specialist trained in measuring thinking and behavioral functions, can help identify cognitive difficulty or dementia. Neuropsychological testing measures thinking abilities such as concentration, attention, memory, language abilities, abstract thinking, spatial skills and executive functions and can help your physician determine what could be causing thinking problems.

Some people experience improvements in cognitive function when they take certain medications or even change their current medications. Talk with your physician about which medications might work for you.

Physical exercise has also been proven to help not just the body, but the brain. Exercise can improve cognitive function as well as reduce the long-term risk of dementia.

In the same way physical exercise improves movement and strength, brain exercise can help improve your cognitive functioning. There are many games and puzzles designed to boost the brain’s fitness, from traditional crossword puzzles to interactive brain teasers modeled after video games. It is important to continually challenge your brain, trying new things creates new pathways in the brain and help keep your brain active and healthier. Try new ways to exercise, different types of brain teasers or even find a new path for your daily walk. Creativity can also enhance cognition and many people with Parkinson’s discover a newfound enjoyment in various art and music projects. Art and music projects may also enhance cognition.

Our Brain Health & Memory Worksheet includes more ways to maintain cognitive functions like memory, planning and problem-solving.

Learn more about how to address cognitive changes in Parkinson’s.

Parkinson’s impact on emotions and mood are often overlooked because they are complicated and harder to talk objectively about than physical symptoms. While a Parkinson’s diagnosis itself can bring feelings of grief and anxiousness for the future, there are also biological changes caused by Parkinson’s that can result in mood changes such as anxiety, apathy and depression.

Anxiety is experienced as nervousness, worrying, feeling jittery, having an unsettled mind or the inability to stop racing thoughts. It is more common in people with Parkinson’s and can occur with or without other mood changes like depression. Anxiety can stem from decreased dopamine levels that come because of Parkinson’s, as well as from the realities of living with Parkinson’s, such as fearing the experience of off-times from medications when you are in public. If anxiety routinely interferes with your sleep or daily activities, be sure to discuss it with your healthcare professional. Anxiety in Parkinson’s can be treated effectively.

Apathy is a loss of motivation to participate in regular activities, socialize or express emotions. Apathy can lead to isolation and avoidance, taking a toll on you and your family and friends. Be careful to not confuse apathy with decreased facial expression (also called “facial masking”), which is another symptom of Parkinson’s and often inhibits your ability to show your emotions.

Depression is ongoing feelings of hopelessness, overwhelming sadness or loss of motivation. It may manifest as depressed mood, memory problems, fatigue, sleepiness and insomnia. Other symptoms of depression include irritability, poor concentration, loss of enjoyment in social activities and hobbies, loss of appetite or increased appetite. Apathy and anxiety may also occur alongside depression.

Depression is one of the most common non-motor symptoms in people with Parkinson’s. Some people experience depression throughout their lives, while others find it is a symptom that comes as dopamine decreases because of Parkinson’s. Feelings of depression may also coincide with the wearing off of Parkinson’s medications because of the same reason.

Depression, anxiety and apathy can have a significant impact on you and your family’s quality of life.

There are different ways to address mood changes, including:

- Taking medications (antidepressants, antianxiety medications)

- Changing medications that have mood-related side effects

- Exercising regularly

- Reducing stress

- Improving sleep

- Improving diet

- Talking to a counselor

- Meditating

Be sure to include depression and any other mood changes you are experiencing in conversations with your healthcare providers. If you experience suicidal thoughts at any point, alert your care team and healthcare providers immediately.

Learn more about depression as a symptom of Parkinson’s

Learn how to identify stressors with our Anxiety Worksheet

Learn how to fight back against feelings of anxiety and depression

Identify mood triggers, add positive energy into your daily life and provide a way to talk with your doctor and healthcare team about treating depression with the help of our Depression Worksheet .

Parkinson’s can have many different effects on your sleep, including trouble falling or staying asleep, vivid dreams, waking up frequently during the night and excessive sleepiness during the day. Like other non-motor symptoms, sleep problems can appear before the motor symptoms.

An estimated 30% of people with Parkinson’s experience some combination of insomnia (trouble falling asleep) and sleep fragmentation (waking up frequently during the night). Studies have shown people with Parkinson’s have different sleep patterns and that their deepest periods of sleep during the night are shorter and interrupted more often than people without Parkinson’s. Often this is made worse by medications that may wear off in the night, causing tremor, painful stiffness or other symptoms to return and disrupt your sleep.

Anxiety, depression nighttime sweating and trouble moving in bed are other non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s that can make getting a good sleep difficult. Fragmented sleep is also exacerbated by how often some people with Parkinson’s find themselves waking up often during the night to use the toilet because of the changes in the bladder that come with Parkinson’s.

Occasionally medications used for Parkinson’s, including dopaminergic medications like carbidopa-levodopa (Sinemet®) and select antidepressants and sleep aids, can cause vivid dreams or nightmares and disrupt your sleep. As unsettling as these can be in and of themselves, this can present serious concerns when combined with another possible effect of Parkinson’s on sleep called Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder (RBD), when the natural processes that prevent you from acting out your dreams with movement stop working. As a result, a person with RBD might yell, scream, kick or get out of bed to “act out their dreams.”

Typically, individuals with RBD report that these dreams are very vivid and that they do not feel rested in the morning. The bed partner often reports violent responses by the person with RBD, which involved being punched, bitten or kicked, while the person acting out the dream is unaware of this behavior. If you or your loved one is experiencing RBD, discuss with your doctor. There are possible medications that can help as well as adaptations and modifications to beds and bedrooms to enhance the safety for the person with Parkinson’s as well as their partner. Some couples living with Parkinson’s discover the safest and most effective way to ensure both partners sleep safely and as soundly as possible is to sleep in separate beds.

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is common in people with Parkinson’s and can present another interruption to a good night’s sleep. RLS is characterized by unpleasant feelings in the legs when they are at rest that is usually relieved with movement. RLS can result from medications and medical conditions other than Parkinson’s, so definitely discuss with your doctor if you are experiencing RLS.

Other non-Parkinson’s-related issues such as sleep apnea, pauses in breathing or shallow breaths during sleep, can make sleep problems worse. While sleep apnea is not more common in people living with Parkinson’s, it does occur more frequently in adults as they age.

Many people with Parkinson’s also experience excessive daytime sleepiness, which can be caused by the various effects of Parkinson’s that interrupt sleep at night as well as from side effects of some Parkinson’s medications.

What you can do right now to live well

There are several medications and other treatments available for many of the sleep challenges Parkinson’s can bring that should be discussed with your doctor. Making changes to your diet, lifestyle, bedroom and pre-sleep routines can also help improve your ability to fall and stay asleep. Exercise during the day and gentle stretching can help and even seemingly small changes, like switching the fabric of your pajamas or sheets, may improve the quality of sleep. Meditation is another relaxation technique that can help to quiet the mind before you go to sleep.

You may also consider seeing a sleep specialist about specific sleep challenges. Sleep specialists typically work in actual sleep clinics or as part of multidisciplinary medical teams at hospitals.

Learn about changes you can make to your diet, lifestyle and bedroom to help improve your quality of sleep with our Insomnia and Sleep Worksheet .

Fatigue is another very common non-motor symptom of Parkinson’s. It can feel like an overwhelming sense of tiredness, low energy, sleepiness, weakness or a loss of stamina when active.

Fatigue may appear alongside sleep problems like restless leg syndrome or mood issues like depression and anxiety. Fatigue can come with non-Parkinson’s-related issues like diabetes, heart and lung disease and hypothyroidism. Poor dietary habits, malnutrition and dehydration can make fatigue worse.

Fatigue can be debilitating in its own right, and also worsen the movement challenges that can come with Parkinson’s since movement control is less efficient and requires a more energy and effort. Motor effects of Parkinson’s like tremor or stiffness or the dyskinesia that can come as a side effect of certain Parkinson’s medications can all leave you feeling more tired by the afternoon or evening.

While taking your Parkinson’s medicines on time can reduce the stiffness, slowness, tremor or dyskinesia that can worsen fatigue, certain Parkinson’s medications may also make daytime fatigue even worse. This can be especially true for a type of medications known as dopamine agonists as well as anticholinergic medications. Be sure to review all medications with your healthcare provider if you are experiencing daytime fatigue or sleepiness to see what is the best combination for you.

What you can do right now to live well

To reduce daytime fatigue, pay attention to what you are eating and drinking. Try to:

- Eat smaller, more frequent meals rather than big heavy ones

- Be sure you are getting enough protein, complex carbohydrates and fluids

- Drink caffeine in the late morning to decrease midday sleepiness

- Avoid caffeine after 3:00 pm if you experience anxiety or have trouble falling asleep

Regular exercise is extremely important for fighting fatigue and can:

- Improve endurance and heart health

- Keep you more awake during the day

- Improve your mood

- Decrease insomnia

Constipation

Constipation is frequently reported by many people with Parkinson’s and can actually appear years before an official Parkinson’s diagnosis. Part of the effect of Parkinson’s on the autonomic nervous system seems to be the slowing down the movement of food through the Gastrointestinal tract.

Certain medications such as various pain relievers and antacids, cold medicines, antidepressants, high blood pressure medications, high cholesterol medications and cardiovascular disease medications can make constipation worse. If you take any of these medications and experience difficulty with constipation, discuss medication options with your doctor.

Diet also can play a role in constipation. Eating more foods rich in fiber, staying physically active as well as drinking more water can help with constipation. Coffee and some teas are also reported to improve constipation, although too much caffeine may end up making it harder to fall and stay asleep. Some supplements such as aloe vera and magnesium can be helpful as well in relieving constipation. Your doctor may also recommend an over-the-counter laxative medication that can be used to ease bowel movements.

A daily routine of 30 minutes of some form of exercise is an important part of keeping your digestive tract healthy and moving and, thus, improving constipation.

Learn more about practical ways to combat constipation with this video.

Incontinence

People with Parkinson’s may also experience incontinence, which is the accidental or involuntary loss of control of urine or bowel movements. This can range from occasional minor leakage to complete loss of control of urine or bowel movements.

There are different types of incontinence that people with Parkinson’s may experience, such as:

- Urge incontinence: a frequent and urgent need to use the toilet.

- Stress incontinence: usually occurs in the presence of some kind of physical stressor such as coughing.

- Nocturia: the need to get up multiple times in the night to use the toilet.

Learn more about changes you can make to your diet and lifestyle to help manage an overactive bladder, as well as treatments to discuss with your doctor and other healthcare professionals with our Overactive Bladder Worksheet .

Many incontinence issues can be addressed by therapy with an incontinence specialist, practicing exercises such as Kegels on a daily basis and by taking certain medications.

Parkinson’s can present a variety of problems related to swallowing, ranging from minor complaints when swallowing pills to severe difficulty chewing tough foods like steak and hard pieces of bread. Swallowing issues are important to address because of the potential risk of aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia is caused when saliva, liquids or food is breathed into the lungs instead of being swallowed into the esophagus and stomach.

Many swallowing issues can be easily addressed with specific swallowing exercises and minor changes in diet. It is a good idea to consult with a licensed speech-language pathologist to identify problem areas and improve swallowing ability through intentional exercises.

Drooling is another common complaint of people living with Parkinson’s that is related to swallowing. As Parkinson’s affects the autonomic nervous system, bodily functions that used to happen automatically, like blinking and swallowing, start to slow down and occur less frequently. Drooling is caused by more saliva in the mouth because of this less frequent swallowing.

Drooling usually begins with some telltale signs, such as wetness on the pillow in the morning and the appearance of saliva in the corners of the mouth. Drooling may fluctuate throughout the day and may progress over time. A licensed speech-language pathologist can provide exercises to encourage you to swallow more often, which will help with drooling. Injecting forms of botulism toxin (Botox®) into the salivary glands has also been found to reduce saliva and help with drooling.

For some people, their sense of smell changes dramatically with Parkinson’s. In many instances, this can be frustrating but relatively harmless. However, in some cases, it can be dangerous. For example, one of our Davis Phinney Foundation Ambassadors told us about a time that her diminished lack of smell could have cost her her life:

“I was told that Parkinson’s disease would hinder my sense of smell, but no one told me the extent that it would. I can still smell many things, but the one thing I cannot smell is skunk. This is where the real problem is: The smell of skunk is what natural gas is added to so people will know when they have a gas leak!!!

I cannot smell natural gas at all. Last year my daughter came to my house unannounced, but it saved my life. When she came in I was in another room of the house but the gas on my stove was turned on ever so slightly. I had been making dinner and I bumped into the stove, turning the knob so it would leak gas but not ignite. My daughter smelled the gas on her way into the house. All of my doors and windows were closed.

PLEASE warn all people who are living with Parkinson’s to get a detector for natural gas. The alternative could be deadly, as I almost found out.

Unfortunately, natural gas detectors are not easy to find. If you’d like to order one online, here’s one option I found.” – Linda Partyka

Living with Parkinson’s can have physical and emotional impacts on intimacy, sexual function and desire.

Physically, changes in the brain and body can lead to erectile dysfunction (ED), decreased libido and difficulty reaching orgasm. Changes in facial expressiveness can hinder communication during intimacy. Common non-motor symptoms such as fatigue, depression, insomnia and constipation can also have profound effects on intimacy and your sex life. The emotional aspects of living with Parkinson’s or being a care partner for someone with Parkinson’s additionally influences each couple’s experience of intimacy. Dopamine agonists (such as Ropinirole and Pramipexole) can, in some cases, lead to hypersexuality and other compulsive behaviors.

Problems with intimacy can be very emotional and may leave both partners feeling vulnerable and isolated. Conversations about what is working, what is missing and what is needed in the relationship can be guided by neuropsychologists and counselors. These specialists are trained to provide coping strategies to maximize sexual health and can bridge the gap with your medical providers.

Learn more about questions to start or continue this conversation with your partner and know when to involve your healthcare provider with our Relationships and Intimacy Worksheet .

Couples may need to be creative about when and how they have sex. Foreplay and touching may become more important. The intimacy that once took place at night may be better experienced in the morning.

While it is not safe to use with certain heart conditions, it is generally safe to use ED medications in combination with Parkinson’s medications. If you are experiencing ED, you may consider consulting a urologist to discuss the best medical approach to managing this common sexual dysfunction.

It may also be beneficial to consult with a psychologist or counselor for specialized training in sexual issues (often known as a sex therapist or even sexologist).

Dizziness or lightheadedness can occur as a direct symptom of Parkinson’s or as a side effect of some Parkinson’s medications. You can also experience lightheadedness if you do not drink enough fluids or restrict salt in your diet.

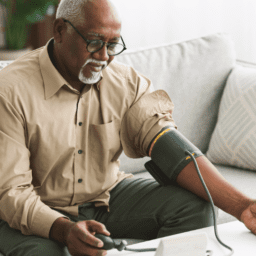

Parkinson’s can lower your blood pressure, as can the medications used to treat the movement symptoms of Parkinson’s. Neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (nOH) is a term used to describe lightheadedness that occurs when blood pressure drops when moving from a seated (lowered, crouched, bent) position to standing. This rapid change in blood pressure and the resulting lightheadedness and dizziness can be one of the causes of falls in people with Parkinson’s. Because injuries from falls and subsequent fear of falling can hamper your quality of life, nOH is an important symptom to address.

While nOH is becoming more widely recognized as a common condition among people with Parkinson’s (one in five people with Parkinson’s will experience nOH), there are a number of other causes of dizziness not related to Parkinson’s, such as dehydration and anemia. Ask your healthcare provider to help you identify root causes and potential solutions.

What you can do right now to live well

Investigate diet and lifestyle changes you can make as well as how to start a discussion about this with your doctor with our Low Blood Pressure or Dizziness Worksheet .

Droxidopa medications (Northera®) designed to combat nOH in people living with Parkinson’s are available and should be discussed with your physician if dizziness and lightheadedness persist.

There are many simple, non-medication strategies that can improve lightheadedness, including:

- Wearing compression socks

- Elevating your legs when sitting

- Drinking more fluids

- Increasing your salt intake

- Elevating the head of your bed by 30 degrees

A physical therapist can also show you exercises to reduce the problems of dizziness when you stand. Since your heart also helps control blood pressure, it is important to discuss lightheadedness or dizziness with your physician.

While psychosis is usually associated with mental disorders like schizophrenia, sometimes Parkinson’s itself or side effects of medications can change your perception of reality resulting in Parkinson’s psychosis. Estimates suggest as many as 40% of people living with Parkinson’s may experience some type of psychosis.

Parkinson’s psychosis typically takes the form of hallucinations (experiencing things visually or otherwise that are not really there), delusions (a false belief or impression that you hold to firmly, even though it is irrational or illogical) or both. Hallucinations and delusions are more common in people who have been living with Parkinson’s for a long time. Some people are aware that what they are experiencing is not actually real, while others are not.

Hallucinations in Parkinson’s can be common, especially during later stages of living with it. Often, they are non-threatening visual hallucinations or visions of things that are not really there.

Other, rarer types of hallucinations include:

- Auditory: hearing voices or music that are not really there.

- Olfactory: smelling things that are not really there.

- Tactile: feeling something touching your skin that is not really there.

- Illusion: seeing things differently than they actually are, such as wallpapers that seem to “jump” or “move.”

Hallucinations and delusions may sometimes be caused by issues separate from Parkinson’s, such as stress, dehydration, bladder infection or general infection. They may also be exacerbated when certain symptoms of Parkinson’s are worse, such as constipation.

Parkinson’s-specific and other medications can cause hallucinations as a side effect and other cognitive symptoms such as dementia may also contribute to Parkinson’s-related hallucinations or delusions.

Delusions are less common in people with Parkinson’s than visual hallucinations but can be harder to manage and live with.

The most common forms of delusions in people with Parkinson’s are:

- Jealousy: Conviction people you love are betraying you.

- Persecutory: Conviction that you are being conspired against or people are planning to hurt you.

- Extravagance: Conviction that you have special powers.

Delusions can result in paranoia, anxiety, anger, suspiciousness, withdrawal, arguments and false accusations, which can be frightening for you and your care partner and family.

If you are experiencing hallucinations or delusions, it is important to have a conversation with your healthcare provider.

Treating hallucinations and delusions with medications can be difficult, especially if they are being caused by medications helping to control motor and other symptoms of Parkinson’s. While more severe hallucinations may require some kind of antipsychotic medication, unfortunately, most medications block dopamine and are therefore not recommended for use in people with Parkinson’s.

Pimavanserin (Nuplazid™) can be prescribed by your doctor to specifically treat hallucinations and delusions associated with Parkinson’s disease psychosis. Other medications like quetiapine (Seroquel) or clozapine (Clozaril®) are also sometimes used.

Parkinson’s affects the autonomic nervous system (the parts of your body that you do not consciously direct or think about). This includes everything from breathing, digestion and the heartbeat. Occasionally, some people with Parkinson’s experience excessive sweating that occurs regardless of the level of physical activity or room temperature. This can occur at night and impact sleep or can happen during the day.

Some tips to help with excessive sweating include:

- Stay hydrated

- Wear lightweight, loose-fitting clothing made from cotton or other natural fibers

- Choose clothing that doesn’t show sweat

- Identify and reduce consumption of foods that may trigger sweating (spicy foods, caffeine or alcohol)

- Identify and reduce stressors that cause sweating (public speaking, crowded rooms, etc.)

If you are experiencing excessive sweating, have a conversation with your healthcare provider to explore how to specifically address this.

It is less frequently reported, but some people with Parkinson’s may experience too little sweating or hypohidrosis, which could be a side effect of an anticholinergic Parkinson’s medication. Too little sweating can have a negative impact on your ability to control your body’s temperature and thus put you at risk for overheating.

If your sweating (or lack of sweating) begins to negatively impact your daily life, consider consulting with your doctor to discuss adjusting your medication or other treatments, such as botulism toxin (Botox®) injections for excessive sweating.

My husband has had episodes of light headedness and low blood pressure for which he takes midodrine 3times a day as prescribed by his cardiologist. He has no other cardiac issues. Would “northera” be the preferred drug to combat the effects of the Rytary?

Hi Lynne, Thank you for reading. I recommend asking your husband’s doctor this question as his doctor knows his situation best.