As an architect and person living with Parkinson’s, Duff Balmer has a wealth of ideas on how to create spaces where people can thrive. In part four of this four-part series, Duff shares information for people interested in the broader social and environmental implications of living well with Parkinson’s. You can read part one here, part two here, and part three here.

How does the connection to nature and the field of ‘biophilic design’ factor into home design and what are the measurable positive outcomes of this type of design?

Humans have an innate appreciation of the therapeutic benefits of nature- when we’re walking in a forest or sitting by a lake, we generally feel better. However, we don’t necessarily know why. Recently this has spawned a whole branch of research called ‘biophilic design’ that looks more scientifically at the psychological, physiological, and cognitive benefits of integrating nature into our homes.

Biophilic design incorporates many principles. These include how we orient our homes to natural views, how we open up spaces to natural currents of air flow and changing patterns of light, and even how we evoke the natural world through the materials and artwork we select. One of the common misconceptions of biophilic design is that you need to live in a rural setting with an abundance of nature to capitalize on its full health benefits. This is not necessarily the case, and even a tiny well-designed garden or balcony within an urban setting can offer significant health benefits. It is, in fact, more about the bio-diversity of this element than its size.

In the context of Parkinson’s, where we tend to spend more time indoors as symptoms progress, the need to intentionally integrate natural surroundings into and around our homes in different ways is arguably even more critical to our health. This is especially true given that so many Parkinson’s symptoms relate to our cognitive health. Here, something as simple as a potted garden close to a window or an operable window that allows us to hear the rustling of leaves or birds chirping can play a vital role in stimulating our senses and, more generally, bolstering our mood.

Through the growing field of research around biophilic design, we now understand that all of these things have a measurable impact on our health. For example, they can lower blood pressure, reduce stress hormone levels, help us maintain a healthy circadian rhythm, and promote a more positive mindset. This research has even led many hospitals across North America to deliberately design patient rooms to include garden views, as this has markedly improved recovery times.

As we consider these natural connections and interfaces in the context of our homes, it is important to consider how we inhabit each space –where we spend the most time, what we are doing in those spaces, and how this may change over time. In the context of a living room, for example, we might emphasize getting more direct natural light within this space (which has been found to raise our energy level) or a more seamless connection to a garden space. In the bedroom, we may choose to position the bed or favorite chair around a specific view or control the lighting to make it more diffuse.

In either case, biophilic design is something we should all invest in when thinking about our homes. The strong connection between nature and our brains makes these choices especially vital for those of us with Parkinson’s.

In designing spaces for those living with Parkinson’s, are there any specific challenges with regard to sustainability?

As we look to create homes to live in longer, we must design with greater sustainability in mind. Flexibility is important in considering the ease with which our home can adapt to changing needs. By designing for flexibility, we are ultimately investing in the long-term viability of our homes. This can have many powerful repercussions: by staying in our homes longer, we can reduce costs associated with moving or renovating, conserve resources, minimize waste, and have greater peace of mind.

This relates directly to the desire many have to age in place and to care for loved ones with health issues such as Parkinson’s within the comfort of their own homes. Enabling a person to stay at home one extra year can alleviate significant costs and stress on family, caregivers, and the health care system.

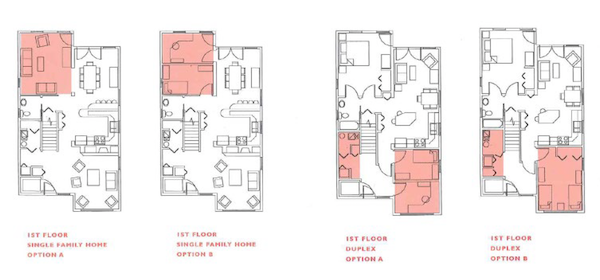

These are ideas that are quickly gaining traction within the industry. For example, we are now seeing new housing prototypes using off-the-shelf technology to create more affordable, healthier, and environmentally conscious housing options. Among their many features, these homes are designed to make reconfiguration easy; walls can be shifted and removed to convert from a single-family home to a duplex or from the main bedroom to a bedroom and home office. Accessibility features are also a prime consideration in these homes in ensuring greater safety and longevity.

Another essential element of sustainability in our homes relates to thermal comfort. Generally, as we get older, we become less resilient to fluctuations in temperature and humidity, and poor comfort conditions can add significant stress to our lives and even exacerbate health issues. This is especially relevant for those living with Parkinson’s, where the ability to regulate body temperature is often compromised.

Creating a home that enables us to adjust the temperature, airflow, and humidity more precisely can help address these growing sensitivities and save energy. These adjustments can be accomplished through items such as operable windows and sunshades you can manually adjust to match your desired environment. You can also accomplish this through carefully zoned HVAC systems with conveniently located controls that ensure air and heat are provided where needed most. In the context of Parkinson’s, ensuring that these systems are accessible and user-friendly is especially important in ensuring that they get used.

What are the primary culprits (within design and construction practices) that allow/introduce toxins into our living spaces?

Just as we have done with our food, it is time that we start asking more questions about the ingredients that go into the building materials of our homes and their possible health impacts. Fortunately, this is starting to happen in North America. Various resources and agencies now aim to safeguard the public by incentivizing manufacturers to identify toxic ingredients in their products. This has led many manufacturers to self-report complete ingredient lists and even innovate new, greener building products.

In the past, these toxic chemicals, such as lead, asbestos, and formaldehyde, have been underreported and have led to what we now know is a considerable burden on our bodies and contributes to many known health problems. Harmful toxins, such as those found in pesticides, can directly contribute to or even trigger Parkinson’s.

We must, therefore, try to build more healthily and sustainably by reducing the harmful toxins we are exposed to. In particular, we should focus on eliminating harmful Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) within the indoor environment of our homes, which tend to off-gas over time. A good rule of thumb when considering VOCs is that materials in closest contact with the indoor environment or ‘breathing space’ of the home should be considered first. Generally, any surface exposed to indoor air or inside the air vapor barrier is worth looking at. This includes paints, sealants, adhesives, lacquers, and certain types of insulation. Similarly, finishes including certain types of flooring, such as vinyl, carpeting, or even hardwood, when finished on-site, can be a harmful source of VOC’s and off-gassing.

Fortunately, there are now many non-VOC options within the marketplace. These are things that a builder or designer can help source when considering a new build or renovation. This requires a certified environmental assessment company that can identify and help remediate in the context of an existing home to ensure a healthier indoor environment.

What role does the space outside the home (community, walking paths, gardens, etc.) play in designing the most Parkinson’s-friendly environment?

As part of the assessment of our home, we need to think about the world around us. This broader context can offer many interesting clues about support, connections, and services that may be available to us.

These connections start at the doorstep of our homes when we consider the accessibility of pathways to the street but also include things like a garden space or porch, which can help to establish and maintain critical ties with neighbors in offering a level of social cohesion within the boundaries of our own property.

By doing a simple audit of the public realm around our homes, we can more fully appreciate our neighborhoods’ long-term viability. This involves an assessment of the walkability of local streets and pathways. For example, are there sufficient accessibility accommodations along frequently used routes to support mobility? Are there places to sit along the way or a coffee shop or friend’s house that can help break up the journey or provide an opportunity for social interaction? Are there places to receive assistance? It is often helpful to walk these specific routes to paint a more experiential picture of what they are like, especially during different times of the day and seasons. Investigating public transit routes and connections is also important when we consider venturing further afield.

The more we understand the physical connections that tie us to our communities, the more we can build long-term confidence and independence in the places we live. Where these routes pose safety or accessibility concerns, this audit may lead to the difficult decision to move to another location where services and amenities are closer at hand, which becomes especially important when driving is no longer an option.

If you could only invest in three critical design elements for your new home design, what would they be?

This is a difficult question. For me, the most critical design elements are all about building long-term safety and peace of mind while maximizing our homes’ essential aesthetic, comfort, and utility. Unfortunately, this is often a delicate balancing act of ensuring adequate accessibility and flexibility while at the same time creating spaces that are uplifting and enjoyable to use. This necessarily demands planning and foresight to design our homes to offer the right amount of comfort and support even as our symptoms progress. Here are three key elements that I would consider for my own home.

It should be beautifully accessible.

Designers often see accessibility features as unwelcome add-ons rather than ones truly essential to a beautiful design. For example, in my home, I would focus on the bathroom space because it is one of the areas where people tend to fall. I would ensure that critical features such as a curbless entry to the shower, non-slip surfaces, single lever faucets, and enhanced lighting were installed from day one. I would also make provisions to millwork and the structure of walls so that grab rails and adequate knee space could be easily accommodated over time. Treating integrated accessibility elements as a design feature ensures that they would blend more seamlessly with the overall aesthetics of the space and feel less institutional.

The example below by Fine & Able shows how designing for accessibility doesn’t mean you have to compromise comfort and style. In this case, grab bars have been carefully coordinated with the plumbing hardware, and the sink has been designed with integrated towel racks that double as grab handles. Highlights of bold color and natural planting also add a nice touch.

It should be future-proofed.

Another central goal of mine would be to future-proof the house for the later stages of Parkinson’s. This necessitates building in a certain amount of adaptability so that spaces such as a ground-floor bedroom or caregiver suite could be added over time. This is always challenging, especially in a more compact (multi-level) urban home, and it requires careful planning of electrical and plumbing systems and ease of reconfigurability of walls that enable the home to flex with changing needs and circumstances. For example, in my home, I would build a ground-floor accessible washroom up front to avoid costly renovations down the road and use a demountable wall system for any future partitioning so that this could be easily removed later. Integrating features early on and having a plan in place would help ease some of the fear and uncertainty that comes with Parkinson’s and extend the years I can live in my home.

In the example below by Best Practice Architecture, a purpose-built home for aging-in-place integrates a ground-floor bedroom and living space. Here furniture is used as a flexible way to zone the different spaces, to maintain a sense of openness and light.

It should bring nature close to or into my home.

Another essential feature of my home would be its connection to nature. Given its urban location, this would involve opening the house to the rear garden with many operable windows and sliding doors. Window planters, raised planting beds, and smooth pavers would also be part of this concept to bring nature right up to the house and ensure the garden remains accessible to me longer. I would also focus on the bio-diversity of this space by selecting indigenous plants to reduce maintenance, create a healthier habitat for birds and insects, and eliminate pesticide use. As my Parkinson’s progresses over time, preserving this connection to nature would ensure that I’m always able to enjoy nature and take advantage of its many health benefits from the comfort of my home.

The example below by La Shed Architecture shows how nature can be brought into an urban home in a very dramatic way by inserting a small courtyard. Of course, this is a higher-end example, and the same can be achieved through more modest means, including a simple balcony planter or potted garden on a window sill.

There’s more to KNOW

This is the fourth post in our series, “Setting Up Your Home Environment to Live Well with Parkinson’s.” You can read the first post in the series here, the second one here, and the third here. Thank you, Duff, for sharing your work and your passion with our community!

Duff Balmer is an architect, designer of living spaces, and person living with Parkinson’s. In dealing with his own diagnosis, symptoms, and future, Duff has begun imagining the many ways that living spaces can be re-imagined, re-designed, or re-configured to accommodate the needs of those with Parkinson’s. “Setting Up Your Home Environment to Live Well with Parkinson’s” is a four-part series presenting philosophies, strategies, and design recommendations to make homes safer, more efficient, more comfortable, and more conducive to supporting the needs of those living with Parkinson’s.

Duff Balmer is an architect, designer of living spaces, and person living with Parkinson’s. In dealing with his own diagnosis, symptoms, and future, Duff has begun imagining the many ways that living spaces can be re-imagined, re-designed, or re-configured to accommodate the needs of those with Parkinson’s. “Setting Up Your Home Environment to Live Well with Parkinson’s” is a four-part series presenting philosophies, strategies, and design recommendations to make homes safer, more efficient, more comfortable, and more conducive to supporting the needs of those living with Parkinson’s.