As an architect and person living with Parkinson’s, Duff Balmer has a wealth of ideas on how to create spaces where people can thrive. In part one of this four-part series (you can read part two and part three here), we asked Duff to share what he knows about setting up your home environment to live well.

Who are you, and how did you get interested in designing a home with Parkinson’s in mind?

I’ve been an architect for the last 25 years, and my wife and I have always dreamed of renovating our own home. After my Parkinson’s diagnosis, I started to think about our home differently. I wanted to find ways to live better both now and in the future. Suddenly, the stakes seemed much higher in the design of our home.

What Approach did you take to the design of your home?

I tried to think of the home not solely around functional issues but also social, environmental, and even technological ones. This realization led to an even broader assessment of our home. We looked at the obvious considerations around the accessibility of our staircase and things like its relationship to the surrounding public realm or its indoor air quality, which play an equally important role in the long-term livability of our homes.

What were some of the major issues that informed the design of your home in the context of Parkinson’s, and what were the changes you made to address these things?

One of the primary drivers of the design of our home was to open up its floor plan to improve safety and overall ease of movement, particularly since those issues can affect movement-related issues of Parkinson’s.

- Bottleneck conditions at narrow doorways presented an increased risk of freezing of gait (FOG) and/or falling. I solved this by removing doorways and walls (where possible) or replacing them with easier-to-manage sliding pocket doors.

- The general lack of open sightlines throughout the floorplan can present difficulties with orientation and supervision, especially if cognitive issues become more of an issue over time. So, I created a new sitting room area next to the kitchen in an open concept to create a more consolidated social hub.

- One of the biggest dilemmas of the design was how and where to transition between the main floor level and external grade so that it didn’t create such a tripping hazard. I solved this by dropping the new sitting room addition flush with grade to eliminate exterior ramps and stairs. A short flight of stairs equipped with handrails, step lights, and accommodation for a future stair lift was included within the space as a safer alternative. This new connection also created a much stronger link to the garden space.

How did COVID inspire and inform discussions for you around modifying residential spaces for those living with Parkinson’s?

How did COVID inspire and inform discussions for you around modifying residential spaces for those living with Parkinson’s?

The pandemic became a global experiment investigating the limits of our homes as impromptu workspaces, exercise studios, classrooms, and entertainment zones. As we were forced to spend more time at home, our individual needs became clearer. It’s fair to say that the pandemic has been a significant disruptor. It forced us to look at existing zones of our homes in new ways and examine new concepts of flexibility, access, security, and comfort.

During the lockdown stages of the pandemic, so many people turned their attention to updating or expanding their backyard or balcony spaces. They understood the importance of this extra space and connection to nature when so many other options were no longer available. There’s a parallel to the experiences of the person living with Parkinson’s who may also become more confined to their home over time and need access to outdoor spaces close at hand. The pandemic has taught us a lot about the value of our homes and how our environment contributes to our health and wellness.

How has reconfiguring your home increased your confidence, improved your outlook, and reduced your anxiety?

Although the design of our home is not yet realized (we plan to begin renovations in the summer), the design process itself has given me a better picture of the issues that will create obstacles over time with my Parkinson’s. Fortunately, the intersection between design and Parkinson’s introduces the element of time into the equation, which leads to an assessment of what design adjustments need to be made and when. Thankfully, the typically slow progression of Parkinson’s suggests that design decisions don’t need to be made all at once; there is time for designs to be imagined in a more graduated way. By thinking through all of the issues, I’ve gained a big-picture view of the design and how it will address my future stages with Parkinson’s—this has given me a level of confidence and helped reduce my anxiety.

As part of a graduated approach, I have designed bathroom vanities to remove center drawers easily if I need to create knee space for a future seated position down the road. I typically reinforce walls for future grab rails so they can easily be added later while also dropping the floor structure at the shower for a curbless entry. As more maneuvering spaces become necessary, the glass fin wall can also be removed as part of a bigger ‘wet room’ concept.

I’ve discovered that even minor adjustments can have major impacts in terms of the long-term usability of each space. These adjustments can subsequently play an important role in instilling confidence. For instance:

- Increasing light levels at a staircase or along a corridor can dramatically improve the safety of these spaces, helping to increase visibility and alleviate freezing of gait, which can occur at critical transition points.

- The height of a bed or the addition of lighting on the path from the bed to a washroom can also help instill confidence in those living with Parkinson’s and in their care partners, especially during OFF times of medication.

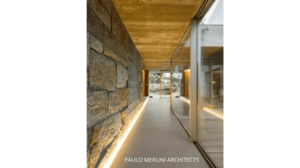

- As seen in this image from architect Paulo Merlini, directional lighting reinforces movement along a corridor. In the context of Parkinson’s, this can help encourage more regular movement and alleviate freezing of gait.

What are the special safety and security considerations people with Parkinson’s and their care partners may want to consider?

Key elements to consider are design adjustments at entry points; these represent a vital element in the home’s overall functionality for the person living with Parkinson’s and their care partner. These zones are often overlooked from a design perspective. Challenges associated with steep topography, improper drainage, and uneven surfaces—especially in different weather conditions—can drastically reduce the homeowner’s confidence and independence.

- The fewer surface transitions within the exterior environment, the better.

- The more generous the dimension of the exterior pathway, the better, especially in areas where changes in direction or landing points within a sloped passage are required.

- A clear definition of the edges of these routes is essential for practical safety reasons; generally, this can be provided through a contrasting border or (in the case of a ramp) a raised curb and handrails.

- Stairs and sharp vertical transitions should be avoided within the main path of travel. An outdoor lift may be considered where the incorporation of stairs is unavoidable—and a ramp is not practical.

- As shown in the photo from Webster Wilson Architects, it’s possible to create a house where ease of movement has been carefully considered regarding furniture placement and the incorporation of uniform/ flush walking surfaces. These design considerations are crucial between indoor and outdoor spaces and when designing accessible routes from the front door to the street.

How do these considerations change over time?

Parkinson’s symptoms progress over time, and our world tends to feel smaller as we’re forced to spend more time inside our homes. Regular interactions with neighbors and the wider community become less frequent, and connections to public and natural realms become more tenuous. With Parkinson’s, we must consciously avoid withdrawing from activities and finding excuses not to do things. By creating spaces that offer seamless connections to our surroundings and are safe places of refuge, the home can remain a positive force in our overall health and wellness. A front porch or backyard garden space can play a vital role in preserving a sense of social connection in these instances and is a design feature that should be closely considered in expanding the boundaries of the home.

There ARE more posts in this series

This is the first post in our series, “Setting Up Your Home Environment to Live Well with Parkinson’s.” In the second post, Duff shared information for people considering moving to a more Parkinson’s-friendly space. In the third post, Duff talked about his experience designing a Parkinson’s-friendly home from scratch. The final post will be for those who are interested in the broader social and environmental implications of living well with Parkinson’s.

Duff Balmer is an architect, designer of living spaces, and person living with Parkinson’s. In dealing with his own diagnosis, symptoms, and future, Duff has begun imagining the many ways that living spaces can be re-imagined, re-designed, or re-configured to accommodate the needs of those with Parkinson’s. “Setting Up Your Home Environment to Live Well with Parkinson’s” is a four-part series presenting philosophies, strategies, and design recommendations to make homes safer, more efficient, more comfortable, and more conducive to supporting the needs of those living with Parkinson’s.

Duff Balmer is an architect, designer of living spaces, and person living with Parkinson’s. In dealing with his own diagnosis, symptoms, and future, Duff has begun imagining the many ways that living spaces can be re-imagined, re-designed, or re-configured to accommodate the needs of those with Parkinson’s. “Setting Up Your Home Environment to Live Well with Parkinson’s” is a four-part series presenting philosophies, strategies, and design recommendations to make homes safer, more efficient, more comfortable, and more conducive to supporting the needs of those living with Parkinson’s.

Do You want to learn more?

Designing living spaces for Parkinson’s can be as complex as a major home renovation or as simple as rethinking spaces and rearranging furniture. More information can be found in our Parkinson’s Home Safety Checklist here.