[NOTE: Want our YOPD Council to discuss anything in particular in future sessions? Let us know what’s top of mind or any questions you’d like to ask panel members by filling out this form.]

During this session, the YOPD Council discusses their experience with non-motor symptoms.

You can watch the video below.

To download the audio, click here.

You can read the transcript below. To download the transcript, click here.

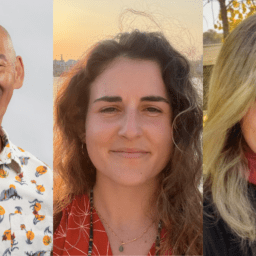

Polly Dawkins (Executive Director, Davis Phinney Foundation):

We are so excited to have some new panel members here today. Joining us as you’ll see we’ve got and hear from our panel members today, we’ve got a variety of experiences, backgrounds, cultures, and we dove into this topic of cultural context last month, really deeply with some guest speakers on another webinar that Leigh can share with you in the chat about, you know, all of us bring a different background to our lived experience with Parkinson’s. And so bringing in some new faces, some new voices today to help develop that more robust experience. And perhaps you’ll see yourself in some of their experiences. So without further ado, I will go off camera and turn the mic over to Heather Kennedy who is going to moderate today’s discussion. Heather, are you ready?

Heather Kennedy (Davis Phinney Foundation Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader, YOPD Women’s Council Leader):

I’ve never been more ready. This is my favorite topic.

Polly Dawkins:

Awesome. Handing it over to you. Thanks folks.

Heather Kennedy:

Welcome everyone to the Davis Phinney Foundation’s talk on the non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. We represent the Young Onset Council and we have some guests here. I’m going to let everyone introduce themselves round robin. We’re going to start with someone who is absolutely so much fun to talk to. I gave him a call last night and we basically solved all the world’s problems together. I introduce you to Michael Fitts.

Michael Fitts (YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Well, how am I supposed to follow up there? That was a great introduction. Thank you so much. Well, first of all, I just wanted to say thank you for the opportunity. I really don’t count it lightly that I was invited here to participate. So I’m looking forward to a great discussion. So a couple of quick things that you might be wondering. Okay. Once again, my name is Michael Fitts. I’m from Alabama. I’ve been diagnosed with Parkinson’s since 2011. And I was 38 years old when I got diagnosed. And so here I am, again, 10 years later, trying to still maintain, you know, improve my quality of life and healthcare

Karen Frank (Ambassador and YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation): You’re muted Heather.

Heather Kennedy:

Next up is a new member of the ambassadors, this is Sree.

Sree Sripathy (Ambassador and YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation):

I mute myself, because otherwise I’ll just be talking all over the place. So my name is Sree and I am a new David Phinney Ambassador. I think I started about three, four months ago, something like that, and I’m not new to Parkinson’s disease. I’ve been diagnosed, I think for six years, symptoms for maybe seven and a half. And I took a cold shower so I could get a nice little dopamine hit to be on point. Let me tell you, cold showers are not my friend. Nope, Nope, Nope. That’s all I have to say for now. Thank you, Heather.

Heather Kennedy: And Kevin Kwok.

Kevin Kwok (Davis Phinney Foundation Board of Directors member and YOPD Council Leader):

Hi everyone. Kevin here. I am 13 years into Parkinson’s and a recent transplant here to Boulder from the Bay area.

Heather Kennedy:

How about you Karen Frank?

Karen Frank:

Hi everybody. My name is Karen Frank. I live in St. Louis, Missouri. I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s four years ago when I was 47 and no stranger before that lived with, my father had Parkinson’s too. So I’ve, had Parkinson’s in my life for a long time, and I’m glad to be here with all of you.

Heather Kennedy: And Kat Hill.

Kat Hill (Davis Phinney Foundation Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader, and YOPD Women’s Council Leader):

Everybody I’m Kat Hill, I’m from Portland, Oregon, and I was diagnosed in 2015. So I guess this makes it six years and I’m super tickled to see some new faces here on our panel, and I’m really happy to be back.

Heather Kennedy:

And I’m Heather Kennedy and you may recognize me as Kathleen Kiddo. It’s just a place where I write for the community of Parkinson’s, and I write from my perspective and it cannot be impressed upon anyone enough that we come to you as if you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s, you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s. That’s why we’re stressing diversity. Cause this disease is baffling. It is unique to each person and we’re learning from each other as we go along. So get your questions ready. And you may wonder what are non-motor symptoms? What are they talking about? The motor symptoms, you know as shaking bradykinesia, which is stiffness slowness of movement, dyskinesias which is, you know, we kind of go in circles. We’ve all experienced a combination of these things at a certain point. There’s also, you know, dystonia, all kinds of things like that, but the non-motor symptoms often don’t show. So I prepared a little bit of a song for you today. And it goes like this, non-motor symptoms, anxiety, apathy, breathing, and respiratory difficulties, cognitive changes, constipation, nausea, dementia, depression, fatigue, hallucinations, delusions, loss of smell, and pain like me, I’m a pain in the, skeletal bone health, skin changes, sleep disorders, small handwriting, speech, and swallowing problems, urinary incontinence, fun, vertigo and dizziness, vision changes, weight management. Shall I go on? And expialidocious.

Do you see what I mean? We are saddled with some things we can’t even believe we have. That was my terrible rendition. So next time you come to see a play, make sure that you don’t have to pay, oh wait, you don’t. This is great. Have your questions ready. Because we want to talk to you about these non-motor symptoms today. I will begin by letting you know my biggest problem is anxiety, anxiety, anxiety, anxiety. Has anyone ever gone to bed and the second you laid down, you think, did I turn off the stove? Did I finish that project? Did I email that person back? Oh my gosh. I think that thing that I did in third grade is going to haunt me for the rest of my life. Or wait, is the dog inside? Is that the dog barking inside or outside? There are a million things that we have to do and nothing in life stops because we have Parkinson’s disease. And when we have young onset, which is only a designation to show how early we’ve been diagnosed, not age-ism not telling anybody they can’t participate. It’s just to show we have different needs, different symptoms, different problems, different issues. That’s all we’re doing here. It’s a complex system. Nothing happens in a vacuum. So if my biggest problem is anxiety, which you may see some times and maybe not sometimes. And I have to develop tools and habits and a new way of life to be able to manage that, so that I don’t destroy myself and everybody around me. So I handle it with meditation, yelling therapy, no, just kidding. I do some boxing though. So I do let some of it out.

I’m not against screaming, but I prefer to be alone when that happens. Not at anyone. I often do journaling, all kinds of things. So what we’re going to ask as we answer some of your questions from the live account, as we go around the circle, we’ll do a round robin with that too. And if any panelist doesn’t want to answer just say pass. Cause what we’re looking for is what your experience of that symptom is. And maybe how you handle it. Or if you have any tips, like anxiety, deep breathing, can you insert a pause before responding. Some days, maybe, some days, maybe not. We’re human, we’re learning, and failing better is what we’re after. Quality of life with non-motor symptoms is possible. So we have a few questions coming in right now. And one that I have been asked before the event so I’m going to cheat just a little tiny bit and let this person slide in and we’re going to go to Michael first. The question is, what can you tell us about mental health in Parkinson’s disease and how does this affect you within the non-motor symptoms? Do you have any experience with this?

Michael Fitts:

I definitely have a lot of experience with it and I can’t really stress enough how important taking care of your mental health and your self-care, mental health in particular. If you’re like me, you have a tendency to overthink things, which is one challenge that I really have. And I think it tends to affect my ability to have relationships with individuals because their constantly saying, why are you overthinking it? Just, you know, so that’s, to me it’s easier said than done. So a part of that too, I really struggle with depression and anxiety. The depression part is really, really challenging and the stuff that tends to come out when I’m at work, which is not a good thing and I’m trying to find some type of balance. One of the things that helped is medication, of course, but then the last time I got a prescription cause I was wondering why I was just feeling just so yuck for lack of a better term. It was like during the pandemic, and I was all like what’s going on with me, what’s, you know, why is this happening?

Why am I feeling so, you know, kind of blahzay. So basically what I did, I was like, well, fool, you’re not utilizing your, not clinical trials, support groups, because the support groups weren’t going on during the pandemic, some were doing it virtually. But the one that I’m affiliated with was not doing it virtually. So it really, really kind of like pushed me to my limits and it was frustrating. So one more quick thing and I’m gonna be quiet. So one of the challenges that I had with the depression and anxiety, for some reason, when I got my prescription, a new prescription, if I would take my depression pill and my anxiety pill at the same time, or in the same day, I would have hallucinations, which is terrifying. I can’t even begin to talk about that, but yeah, it was terrifying.

Heather Kennedy:

Yeah. There are some things that are happening within us, both chemically and causal. So there are things out here we’re dealing with and then there’s a chemical change within us and our meds are never quite the same. So they’re when you mentioned terrifying, it could be anything from psychosis to just feeling a little bit out of control to noticing that you’re saying something, you’re sort of watching yourself say it or do it. And you know that it’s not quite you. Very terrifying. We’ve all had this experience, which is why I think mental health is so important. Yeah. So the next question we have coming up here, we have some questions coming in. Oh, okay. Excellent point. I’m going to read you something that somebody wrote here before I go on to the next question, “I found that in order to control my anxiety, I try to break things into two categories. Things I can manage and things I can’t.” That’s sort of like the serenity prayer, and that’s so important. What you can’t manage, you can outsource, ask for help. You’re very clear and specific because sometimes just say, I need help to people. They might not know what to do. And then offer other people can for ask if other people can offer insights or help. So does anyone have any insights on anxiety? Let’s go to Sree.

Sree Sripathy:

Well, thanks for that one. I will say in regards to, in regards to what Tom wrote, that if I could outsource sleep, eating, working, thinking, and I could just sit in front of Netflix all day and watch TV, that would be fantastic, but I cannot. In terms of anxiety, I’ll just be honest, although there’s no point in being dishonest really, so that doesn’t really make sense. I’ve pretty much had anxiety, I think my whole life, but the interesting thing is nobody has actually noticed that I have anxiety cause I’m really good at hiding it. So I don’t have anxiety over the same things that other people have anxiety over. Like I don’t know what that could possibly like yes getting up on stage, speaking here at the webinar, I had a lot of anxiety and then right before things just kind of crystallize and they just center.

Right. But the anxiety could be like, am I lying in bed properly? Or did I make my tea right? Or am I pressing the buttons on the phone? Why are my fingers trembling? Why can’t I, you know, why is the shaking preventing me from dialing a number? Oh my God, what if I can’t dial 9 1 1 properly? What if I can’t dial my mom? And then there’s a lot of negative self-talk and self-hate and a lot of that stuff that makes everything worse. So it’s all a lovely kind of cycle of things. And you have to do a lot of deep breathing. And then I remember, oh my gosh, deep breathing is hard. And I get tired of breathing. I get tired of talking. I get tired of thinking. I get tired of everything. And then I’m like, I’m just going to take a nap.

And then four days later I wake up and I think, wow, this is great. You don’t have to take a shower at all if you don’t want to. And so then I think maybe that’s apathy and I’m like, I don’t really know. I just don’t feel like thinking about it. So, and on and on it goes. And usually there’s a moment that you have to have some sort of, I think a visual cue to break you out of it. So sometimes it might be like my boss calling me and saying, you haven’t been to work for a week. Just kidding. That’s actually never happened. Don’t worry. I show up to work. Anybody watching, I show up to work. But it’ll be something like an alarm going off or a song. I have to have something to snap me out of it.

A lot of the times that’s friends and sometimes it comes to a point where there isn’t anything outside of yourself that snaps you out of these sort of, kind of states of anxiety or apathy, or just like a fugue state, if anyone understands what I mean by that, you just have to wait for something to click in your brain and say, I need to call somebody. I need to reach out to somebody. And then I’ll start calling people, texting people. I’ve developed a community for myself, of friends that I had, you know, who have been friends with me for 20 plus years, 30 years, and then newer friends, you know, who I’ve met since I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s and my friends with Parkinson’s. Those are the people I rely on every single day to get me through some really tough times. And so I just got to remember that they’re there. I don’t know if that’s very helpful, but I hope maybe somebody got something out of that.

Karen Frank:

I thought it was, I loved, I just interject here Sree. I loved how you kind of walked us through what it looks like for you on a regular day. That it’s not just the sort of, sorry, my dogs are going to start barkingright now. Anyway. I love that. I’ll mute.

Heather Kennedy:

The dog’s like yeah. What she said. Yeah. That lady. Have you ever noticed when someone comes to the door while you’re recording and they’re like, they’re here, they’re here. Maybe they have treats. And you’re like, I’m doing a recording. So our support dogs are real supportive. So I also like how you mentioned Sri, what I often call a touchstone, someone to just check in with, even if it’s like, I think my meds might be off, which you might not notice because when your meds are off, it turns out it’s hard to tell or just someone to touch base with and say, I feel depression on the horizon coming at me. It’s the four horsemen of the apocalypse they’re coming in fast. You know, can we just have a talk today? Or just asking specifically like, Hey, can you help me out with something at three o’clock or what, you know, whatever it is because people want to help. But if we’re vague, yeah. They won’t know what to do.

Sree Sripathy:

Yes. I will say this one quick thing. I don’t want to take up the conversation cause I will do that. So just kind of cut me off. The one thing I will say, it’s people who have Parkinson’s disease or other conditions like depression, or even ALS you know, I’m on Twitter. I talk with a lot of, you know, people online that are able to understand. So my really good friends who’ve been with me for decades or even just seven years, whatever it is, good friends. They’re wonderful. They’re amazing. But they often don’t understand. And it’s, I think it’s frustrating for them because they don’t really know what I need or they don’t know how to give it to me. Even if I walk them through it. And I’ll say something like, say something like this, or this is what I need. There isn’t that understanding.

So I also think it’s really important to find people with Parkinson’s or other mental, I don’t know what the politically correct word is, mental configuration challenges. There you go, health challenges to connect with because we can also learn from other people with other conditions. People have depression, people have anxiety, people with multiple sclerosis, people with ALS. There’s a lot of stuff we can do as a community of people who have a condition like this and similar conditions to work together. And so I think that’s really important. Thank you. And I’m done speaking.

Heather Kennedy:

Please. I invite you to keep going whenever you want, Kevin, you had something to add.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah, it’s funny because I feel like sometimes we are dealing as Sree said with a audience of friends and family that don’t understand. And I mean, I just came back from the Bay area from a family reunion and one of my family members there is a prominent neurosurgeon who’s in his eighties or nineties even. And it was really interesting to hear him ask me about Parkinson’s. And he told me how he trained in Europe on a special Parkinson’s fellowship. And he described the telltale symptoms and not one of them was a non-motor symptoms. And if that’s the way physicians have learned and trained, you can imagine how there’s a lag time for others to pick up on it. And I just, you know, I just thank God that, that there is so much attention to non- motor symptoms today. I don’t think a newly trained movement disorder specialist will ever just say that you have motor symptoms, but they do oftentimes default to UPDRS and they don’t ask you and they give in short time that you have, how has your mental state, how has your apathy, how are the myriad of it?

I mean, just think about it, right? Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators control every system in the body. So why wouldn’t we have problems with everything from sleep to constipation, to everything else, right? It’s given that they’re all going to be affected. In some ways, since this is a topic on non-motor symptoms, I’ve sort of given up on chasing individual symptoms, because you’ll be chasing your disease for life if you do that. And instead, what I do is I cluster the symptoms and say, how has this impinging on my work? How is this impinging on my socialization and things? And then usually I’ll find four or five different non-motor symptoms that will come into play. It’ll be anxiety. It’ll be, you know, the fact that I’m drooling sometimes.

It’ll be the fact that, you know I swallow and choke in public or communication becomes a big thing, right? I mean, I can’t type because of the dystonia, I’m losing my voice towards the end of the day. I can’t get words out. So you cluster all those into saying, how is this, how are these various symptoms affecting my work? Or how are they affecting me? So I’m rambling a bit on here right now. But what I think we have to do is we need to educate our families, our friends, our employers, that it’s not just UPDRS. You know, the fact it is much more than that. And I think it’s our obligation because no one else is going to educate them other than us.

Heather Kennedy:

And no one can read our invisible cue cards or know what’s going on. Sometimes we don’t even know what’s going on. Like the invisible third-party that was uninvited, it’s beating us up. And everyone around us is getting shoved around a bit too, which leads me to the next question here about sleep. Sleeping hours are obviously the key to improving motor function and mood, but we have sleep problems. Kat, can you talk about some insomnia with Parkinson’s.

Kat Hill:

Well with Parkinson’s and with treatment for Parkinson’s and it’s sometimes hard to sift out I think for all of us, why we’re not sleeping, are we sleeping because of the disease process or are we not sleeping because of the disease process or because of the treatments. And I think it’s really a, it’s a toss up and I think it takes some trial and error, just like so many other things with this disease. And but I think it’s really important that we’re talking about it and we’re talking about it with our providers, because sleep is one of those things. As we all know, even before we had Parkinson’s can really impact how we’re feeling in our day. And I know for me, I was having a lot of insomnia on the agonists and you know, I was getting a lot done all hours of the day and night, but it really impacted my ability to sleep and to stay asleep.

So I think staying in touch with what our expectations are and paying attention to changes and do those changes come on with a change in medicine, a change in dose, a change in symptom. And I’m not saying it can always be addressed or always be fixed because it may inherently be part of the disease process. But I think staying aware of it is really important. And talking about it, talking about it with our loved ones, trying to listen to our loved ones, if they’re giving us feedback, Hey, you know, I’m noticing you’re not coming to bed until three in the morning. And you’re up before I am at six, what’s going on?

Heather Kennedy:

I also got another question came in about sleep, that I’ll just add to the conversation here. That was a comment from Fulvio in Barcelona. Hello. It’s so good to see you here. And the next one, and then another comment was from Chris. Hi, Chris. And this one is from Rui in Portugal. Wow. We’re getting around the globe today. He adds, normally what I have important tasks or meetings the next day I sleep less hours and stay awake. And I don’t feel anything other than I’m not asleep, I’m not asleep. And then his question is our perception of our own feelings is damaged or reduced. And our sensations as well, like smell. And he’s saying, is there any way to detect that or change that or shift that? I’m not really sure exactly if that’s what he meant, but that’s what, that’s how this reads. So what I’m thinking Kat is to add to that. How do we tell what’s affected by sleep? I would go with everything. What do you think?

Kat Hill:

Yeah, I would totally concur with that. After years of being up all night, delivering babies and doing all kinds of weird hours. I know how much recovery time it took me when I was practicing. And initially how much better I felt when I was sleeping on a regular basis. So I know for me, I also try to accept part of it. Like if the next day is a big day, I try to just say, okay, I’m going to not judge it for tomorrow. Cause I know tomorrow’s a big day or I might sit and write down all my concerns on a piece of paper and keep the tablet right next to my bed, but then expect myself after the big day has passed to be able to sleep better instead of worrying so much about it. There’s a level, I don’t want people to think that they should just accept when they don’t ever sleep. That’s not what I’m suggesting, but more, if you find a pattern of, you know, the day before the big meeting that you sleep, well, maybe try to stack up a little bit on the front end and then on the other side of it and just roll with that a little bit.

Heather Kennedy:

Excellent idea to keep that pen and pad by your bed. Yeah. Does anybody have anything to add about sleep? Sree.

Sree Sripathy:

I do. But I just wanted to make sure like if Karen had anything, because I don’t like Karen looks just gorgeous sitting there. I’m like, do you have anything?

Heather Kennedy:

Yeah we got a question for her next.

Sree Sripathy:

Okay. So my real quick thing is, so I had my first webinar to do for my job last week on a Thursday and I have avoided doing webinars my entire life, my entire history. So this is only my second webinar in my entire life. And I hate being recorded. I hate all that stuff. So it caused me enormous anxiety. And so on Tuesday I kind of slept okay, Wednesday through Sunday of last week, I slept a total of 10 hours. So that is when most people get an average of maybe six to seven hours a night, you know? And that’s even not that much, really. You really want, maybe some people would love to get eight or nine. I slept zero hours from Wednesday through Saturday and maybe two hours on Saturday and then four on Sunday. And then I just could not go to sleep.

The anxiety, the thoughts in my head were overwhelming. And then I’m just thinking, oh wait, I’m doing great. This is how smart I am on like 10 hours of sleep. Give me a Nobel prize right here. Give me a Pulitzer. This is fantastic. Maybe I should go drive and get coffee. And I’m like, that’s actually not a good idea. Do not drive on that little sleep. But what really surprised me is I was assuming that once I crashed I’d finally get like great sleep. Like, oh my God, I’ve been up essentially for four to five days straight with little to no sleep. I am now going to get eight hours of great sleep. You know what, no, I got four, I got four hours of basic sleep. So for me, what I’m realizing, and it’s very hard for some of us who are addicted to technology, how our brains are wired, particularly if we’re working full-time and jobs or we’re connecting with family.

Or we’re just like, Hey, I can chat with my friends in Portugal or my friends in Barcelona and talk about PD. It’s hard to put that all away. So for me structuring my day where I shut everything down at 9:00 AM, 9:00 PM is very difficult. And sometimes I have to do that for days and days and days for me to even get a decent sleep. And sometimes it still doesn’t work, but I got to keep trying it because my doctor just looked at me the other day with this kind of like intense look that he’s never given me before. I’m like, okay. Yes, doctor. Yes. I will do everything that you say. Yeah. So, basically lack of sleep sucks.

Heather Kennedy:

Yes. And the next question actually asks that, can I have Karen asked answer that first Kevin? Or do you need to…

Kevin Kwok:

I was just going to add the sleep, but if we’re going to stay within the

Heather Kennedy:

It’s a little yeah. It’s within the topic. Yeah. Cool. Okay. So I’m going to ask Karen, and then I’m going to let you go and say that. Okay. So someone wants to know the, the impact of excessive daytime sleepiness, which is, I guess, EDS, there’s a whole other world that we can get into here. Have you ever, Karen Frank, this is for you, fallen asleep, doing something like you should do the head nod, like you’re on a plane, anywhere because of the Parkinson’s. And if so, how do you handle this excessive sleepiness?

Karen Frank:

I did experience excessive sleepiness at one time as a side effect of dopamine agonists, it was the rotigotine patch and at the time I was very, very nauseated from the medicine. So I couldn’t really, I couldn’t really tolerate coffee, which was my go-to for what I was going to do when I was tired. And so my movement disorder neurologist suggested that I try a caffeine pill. I mean, I’m not advising people to do that. That’s what my doctor said to me. And that was a good solution for a temporary problem for me, because I was only experiencing the side effect for a period of time. And I also found that my nausea at one point resolved and I was able to resume just drinking coffee and that kind of thing. Now I just sort of try to live, it’s different now since I’m not working.

Cause I remember having tremendous anxiety about not sleeping and being too sleepy at work and taking call. I had a job where I was in the operating room at night as well, doing anesthesia. And I was terrified that I would be sleepy at night and make poor decisions. And you know, my performance in my job was like on the edge of a razor. And I just knew at any moment that that one little thing could tip me over. And that’s when I realized, so I need to take a step back and make a decision not to practice, but as far as daytime sleepiness now in my life, I don’t really struggle with that. I have plenty of other non-motor symptoms, which give me a run for my money, but that one is resolved for me, which is a good thing.

Heather Kennedy: And Kevin.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. I’ve come to learn that there’s sleep is a very complex thing. There’s insomnia, which some people talk about, there’s fatigue, which lack of sleep can give you. And then there’s excessive daytime sleepiness, which is more my problem. I mean, I’ve finally mastered through just different concoctions and homeopathic ways, ways of getting eight hours of sleep so I can get the eight hours, but then I wake up and the first thing I do is if I have coffee in the morning, do the crossword puzzles and want to go back and take a nap. Or like, as you described, I cannot stay awake in a moving car. It’s impossible. And my kids, you know, we used to go to movies and they’d always say, dad, you’re snoring at the best part of the movie, every time right? So it’s this excessive daytime sleepiness that is my issue. And it’s something that I’m trying to get a handle on.

Heather Kennedy:

There’s a reason why we fall asleep in cars. It mimics the womb, the rocking motion, the white noise. That’s why there’s something called ASMR that’s used for certain sounds to put us to sleep. It can be one way to put us to sleep or the rain sounds or things like that. I’m getting some really great feedback from may I read a few things that are coming from the audience. Brian in Nevada. Hello, Brian, it’s important to share those changes with the MDS, put ’em in a note and make sure that you have access to them at your next appointment. Cause we often get in there and then we freeze and we’re so excited to see our MDS we forget to ask them everything, make sure you bring those notes or bring somebody with you. Steve talked about his non-motor symptoms, hi Steve, bouncing and changing, shifting every several months. So for a few months he can’t smell or taste things. Then the next time he can, or if it’s something else like swallowing or constipation or incontinence, whatever, it keeps changing. It’s like a flavor of the month. So we’re going to go to Michael to ask him, what would you say about the symptoms constantly changing and also as a caveat to that, I’m going to add our meds are always changing too. What do you do about that?

Michael Fitts:

Well I think communication is key. And let me say this and I don’t know if anybody else has experienced it. So it seems like the appointments that you’re going to with your movement disorder specialist keep increasing and getting pushed back. Like sometimes I can only see my like once a year. And I think maybe a nurse practitioner the other time at the six month range, but like I said, communication is key. So if I would have been on top of my mental challenges and understanding why I was going through, I was going through anxiety I would have picked up on it, you know, a lot sooner and wouldn’t have had to go through all of that. So if it like everything else having to do with Parkinson’s, it’s just really, really tricky. And I think different people have different coping mechanisms with that.

But like I said my point of choice would be talking to somebody even if it’s just that one person that confidant that you can have in order to kind of like get you through that. Now, something Kevin said earlier kind of struck me and he was talking about how we need to train I guess our friends and family. I would argue and I know this is going to be controversial, I would argue that people with Parkinson’s need to get additional training have different circumstances and different things to learn. And I’m gonna tell you, it usually starts with this cause this irritates me and I know people mean well and they don’t mean to be negative. So it irks me when somebody comes up to me and says, you don’t look like you have Parkinson’s, I’m not exactly sure what it annoys me so much, but it really does.

And like I said, I think that people have your best interests at heart. And they think that that might be a compliment and who knows maybe and so work university is a compliment, but I do think that we need to you know, train our individuals that have Parkinson as well. So I don’t know if that makes sense to anybody because that’s just something that I know I deal with on a fairly regular basis and I really have to keep myself at bay because like I said, I know that they’re not trying to be disrespectful or mean anything by it. But sometimes when you hear that so many times it just really gets to you. So you don’t look like you have Parkinson’s, we thought you were the speaker. Okay. That’s well and good, but I’m not. And then the other thing is that adds a level of complexity about it is too.

Oftentimes when I’m in those settings, I tend to be the only person of color in the room. And so, you know, believe it or not, I think people including myself at one time were not really familiar with any person of color that had Parkinson’s. Cause I was in denial for a while myself because I was like, well, the only two people I know that had Parkinson’s that were, you know, prominent, was of course Michael J. Fox and then Muhammad Ali. So I didn’t really count Muhammad Ali because he had taken so many kicks to the head and to the brain, so you know, I didn’t really count him, but that’s just some of the ways that I kind of deal with it and have noticed it how people act and how they respond.

Heather Kennedy:

Right. And you work in diversity too, as I understand it.

Michael Fitts:

Right. I do. I do. Yeah. Thank you for bringing it up. So I do work with diversity as a part of my everyday responsibilities. And it’s really, it is really interesting. And I think that you all might be able to understand this or coincide with it. So most of the time, when you say diversity, it’s been my experience that people think that you’re talking about race or gender, they may be the LGBTQ+ community, but that’s just, that’s not it, there’s so many other things that we deal with. So there’s people that have different, you know, how people have different learning styles, they have different ways to communicate as well. So you have person A over here that is an introvert. And so you want them to give feedback at a meeting with the whole company and they just kind of like shut down. You can’t really do that. So those are the types of kind of like thinking outside of the box, having to deal with what that can really be affective to survive. But you have to really understand and realize it and have somebody that’s you know, really, really open-minded because if you’re not having a physical tremor, that’s when they say, well, you don’t look like you Parkinson’s, but it’s just so much more than that.

Heather Kennedy:

Oftentimes too, we’re sort of faking being well, like I take extra meds when I come to you here. Absolutely. You’re not seeing me OFF. Right. Yeah. And so our friends see us when we’re on cause that’s when we leave our houses. Right. I mean they’re so they have nothing to compare it to. Kevin, you wanted to add something.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah. Sometimes we actually even fake it with our physicians. You know, how often do you go in to see your physician? And you say, well, I’m fine. Right? Everything’s gray. So I use the term in my talks. Now, when you have Parkinson’s you don’t fake your disease, you fake your wellness. And I think we’re doing a real disservice when we fake it because people don’t get an accurate picture of you. And if you can tell, predict your symptoms, how is someone else going to predict them?

Heather Kennedy:

And do you want to add something Sree?

Sree Sripathy:

Yes. I whoa. The whole setup, just switch. That’s a little disconcerting. So I will say in terms of what Michael was saying that only when I think, not only when I think, good God, what am I trying to say? My brain is like foggy. Okay, hold on. Let me slow down. Only after I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s, did I realize how little people with disabilities are even taken into account when it comes to diversity? And I think, I might’ve thought a little bit like that pre, but it’s only after that, I looked everywhere, walking into bathrooms at the airport, walking down the aisle of the airplane, going into a restaurant and I’m talking, you know, somebody in a wheelchair, somebody with a tremor, someone who’s older and no disrespect to anybody who’s older, whatever older means to you.

But if you’re 80 years old and you’re traveling, where’s the extra help at the airport? I’m not saying being old as a disability, but it’s certainly not, you’re not a fit 22 year old who’s like a former football star able to lug your luggage everywhere. You know? So I’m looking at all of these things. So that is huge. And people with disabilities, I would dare to say are some of the most invisible people because when you’re actually having your disability, when you’re OFF and that’s, I think what Kevin was mentioning a little bit earlier and I think Ruby also our know somebody else in Portugal, might’ve mentioned this too, on the chat, you’re not going to go out. You know, right now I am dyskinetic and I’m really like, I can feel it happening and I’m trying to like tighten everything in my body so it doesn’t appear that I’m dyskinetic.

So I’m trying to kind of hold in the energy, so to speak, but it doesn’t work. And sometimes I feel like my brain cells rattling around in my head. It’s exhausting. So fighting it is exhausting, having it as exhausting. And you don’t want to go out when you’re like that. Right. So people don’t see us. Right. And also in terms of what Michael said, sometimes I wish I had like the dyskinesia power. Like you don’t think I look like I have Parkinson’s I’m going to click my dyskinesia button and now what do you think? And of course that’s not, Parkinson’s, it’s the side effect of the medication, but you know what I’m saying? You know, it’s like, if we can just turn it on so people can understand. And what’s interesting is when I went to my new doctor, I switched insurance and I have a new doctor who’s actually my old trial doctor. That’s another story.

I spoke with the nurse who took me in and I told her this, and this is reflecting on what Kevin said. I said, I am embarrassed to go see him because I’ve progressed. And I started to get really emotional and teary. And I was surprised myself. And I said, what if he thinks I failed? And I’m like, how does that even make sense that I failed? Because I keep thinking, I can control my progression. I can fight against it if I just do everything right. And you know what, I could do everything right. And I’m still gonna progress. And God knows I haven’t done everything right at all. I mean, definitely not. So I was really embarrassed to go see him after two years because he’s my trial doctor before, now he’s actually my MDs. And I was trying to put on a performance and it just so happened that I did. And I told them, I said, I’m just performing well for you today. You’re not seeing everything. And my, the nurse had to tell me, you did nothing wrong. You don’t have to feel like you failed. And I was still shocked that I could have those types of feelings, but I did. So sometimes that parlays into it too.

Heather Kennedy:

Yes. And I believe that I skipped Kevin during the last round Robin. Is that correct? So I’m going to ask you this question next, right Kevin?

Kevin Kwok:

Oh, sorry. I was just typing a response to someone about opening pretzels on a plane.

Heather Kennedy:

I don’t know what you mean. I can’t open anything. I wanted to know did I skip you on the last round Robin

Kevin Kwok:

No no you didn’t.

Heather Kennedy:

I didn’t. Okay. Well, I’ll give this to you. I’m going to throw this at you, Kat. Someone wanted to know about turning off their brain and then turning on their brain. How do you know how to be on or off? And then I’m going to also add, Tom also that said, hi Tom, in order at night to get his brain to stop working, he listens to old timey radio shows like with all the noises, like Larry Gifford was joking about mystery theater type stuff. And then he also tells his brain it’s okay to shut down, talks to his brain, it’s big brain. And then, you know, within two minutes of the show, he’s asleep. So that’s a little side effect or side bear. Also Mark mentioned meditation. Kat, what do you think?

Kat Hill:

So I think in a perfect world, we could all just tell our systems to stop and start and off and on. And whether we have Parkinson’s or not, right. I mean, I’m sure many of you pre Parkinson’s had race brain and you know, some anxious moments, you know, before the test or whatever. And I think that all of us have to learn tools that are gonna work for us. Some people, some of the sleep experts say, you know, no screens, nothing that’s light stimulating, have a sleep hygiene routine, meaning you kind of do the same thing every night at the same time. And I think all of those things are super well-intentioned and might work for some people. Yeah and Karen just typed in mindfulness. Absolutely. I think part of what we’re not good at is excepting kind of what is, and that this may be challenging and also giving ourselves permission to use tools when we need them and to ask for help when we need it. I think mindfulness and I think distraction also can be really helpful. Meditation, and sometimes there’s meditation tools that will actually guide you through like a guided meditation. Sometimes that can be really helpful. But I’m not here at all to claim that I have the answer for everybody. I can tell you the tools that I’ve used that are helpful. I like to listen to, you know, murder podcasts, not super relaxing for a lot of people. For me, it really works. It’s good distraction.

Heather Kennedy:

How about the meditation with the murder?

Kat Hill:

There you go meditation murder.

Heather Kennedy:

We’re coming up behind you.

Kat Hill:

And I think I don’t have this anxiety of like, well, what if I fall asleep at the good part, because you can always go back and replay it. And, and I find that if I’m listening to kind of a soothing voice, even with a really scary story, I do okay. So I think for me, it’s taken some trial and error. I also want to stress that also for me, if I’m not exercising long and hard during the day, I don’t sleep as well. It’s sort of like my body doesn’t get the workout that it needs. And so it’s not cooperating even if my mind’s ready. So those are the tools that have worked for me. And if anybody has the on/off switch, I want to hear it because I want it.

Heather Kennedy:

Right, can that get installed. Kevin and then Karen wanted to add some things to what you said.

Kevin Kwok:

One of the things is that you we can’t put all the onus on our neurologist to find the solutions for all the myriad of issues that we have and I would encourage everyone to build your own dream team of, you know, your physical therapist, your occupational therapist, your neuro therapist. I mean, because it’s in between those annual appointments, Michael, that you talk about that you still need care. And if you take control, if you recognize what your symptoms are and what gives you relief, that’s up to us to find our formula that works. And the team that works for us. It’s not just your physician, because it’s too complex and the system doesn’t allow us enough time with the neurologist to get all the answers.

Kat Hill:

I totally agree. I totally agree with that. Kevin, I think that, and we are the experts at our disease. If you just look at the panel of us that are sitting here today, how different we’re describing some of these non-motor symptoms, can you imagine if we got a thousand of us together and did this round robin, we would probably get a thousand different answers. So we’ve got to own our own experience and you know, the world’s full of information and we’ve got to learn kind of the tools that work for us in tandem with seeking medical advice and getting treatment with medications. So.

Heather Kennedy:

And Karen had something to add.

Karen Frank:

Oh, I think Parkinson’s is a very dynamic condition right throughout the day from day to day throughout the years, it’s a changing and fluid condition. And I think this concept of on and off which we are subject to at the whim of our medications and our disease, I think the key is not about changing the external. I think it’s about changing the internal sometimes, and that we have to build that muscle and that skill to be able to just be, and I have a friend who says, you know, you got to learn how to be a hippie. I think that it’s an important, you know, piece, because right now you know I was joking with someone before this, this talk. I don’t always put on makeup and stuff like that. I decided I’m going to put on makeup. And my tremor is particularly bad right now.

And I wanted to put on some eyelashes and I used to just get endlessly frustrated with this. This is a motor symptom, but I actually think it’s really funny now. And I’m like having a conversation with my hands. I’m going to do battle with you. You know, I say a bad word, so I’m not going to say it right now. And I call it a bad word. And I say, you know, we’re not gonna, you know, I’m not going to lose this battle today. And I try everything, you know, tweezers and fingers and poke my eyeball and do all this stuff. But you know, that’s a motor symptom, but I have to do that with the non-motor symptoms too, because, you know they come and go as well and different situations, different times of the day and side effects from the medication. Here’s an example of a side effect of a medication that created a horrible non-motor symptom for me.

I developed an eating disorder from levodopa. I was on higher doses of levodopa. I developed a binge eating disorder. I went from a size two to a size 14. I gained a ton of weight, that had its own baggage, which was depressing and difficult and hard to deal with and expensive and, you know, lots of different things. But I felt so bad about myself because my husband would say to me, like, why are you eating a thousand cookies if you’re gaining a thousand pounds? And he didn’t mean bad about it. He was trying to like, keep me in check and say, you know, but what I’ve accepted, this is what I’ve accepted. The eating disorder actually went away when they made some medication adjustments. But what I’ve accepted is that I have to learn how to be a little more flexible.

I have to learn how to be a little more willing to be uncomfortable, and to realize that it’s also going to pass. It’s not a tattoo. It isn’t permanent. It’s a temporary state of being. And I have to remember that even if I had a bad night’s sleep tonight, that doesn’t mean tomorrow is going to be bad and you have to be present. And I think living in recovery from substance abuse, I’ve dealt with that issue. You know, these medications, and I’ve learned that you have to learn how to be in the moment and, you know, going down the rabbit hole of the future and worrying about what’s yet to come really is an unproductive state that’s going to ruin today. But these drugs, these medications, the anxiety of the disease, they cause rumination, they cause obsessive compulsive disorder. They cause mania, they cause racing thoughts.

You know, these are real and present and true things. But I think the key is what Kevin was talking about and others in the chat about building your dream team. Part of my dream team is a psychologist, a really fantastic psychiatrist, a great chiropractor, a primary care physician who is good with mental health issues. I fired my last primary care physician because she was annoyed when I would call her with anxiety. My new primary care physician will sit next to me, she’ll put her arm around my shoulder and she’ll say, it’s okay. I’m with you. We’ll do this together. And to me, I felt like that was the most empowering thing I could do was to find a doctor who works for me, with me. I don’t mean works for me working for me. I mean, her style, her personality, her caring, and that changed everything for me.

I went from really bad about all this anxiety to, oh, it’s okay. It’s part of my disease and I’m going to learn to live with it, but I’m not going to let it beat me. I think you do have to find a way to live with these things and improve them. And last word is my husband and I have like a little code word and it makes me laugh when I’m going off and kind of getting anxious or spinning out, he’ll say, use your strategies. And we just look at each other and laugh, but it’s so true. You know, the mindfulness, the meditation, deep breathing, dial a friend. Those are important.

Heather Kennedy:

We are getting a lot of questions right now at the end of this. So I just want to move it along about depression. I’m going to move on, actually, Karen, you can start this and then we’re going to pass it. Just like give a little brief bit and then we’ll pass it to Sree and we’ll let everybody talk about this one. How do we handle the depression of Parkinson’s? It’s often not discussed in depth or the real challenges that come with it, this is from Brian. Hello, Brian, I’m glad you’re here. And we all have, have felt this in one way or another, but there’s often no language for it. There’s a stigma and there’s some shame attached to it. So can we hit that real quick around the robin here?

Karen Frank:

Did you say you wanted me to start?

Heather Kennedy:

I’d love for you to kick that off and then we’ll go through.

Karen Frank:

I’ve dealt with depression throughout my life. It may be related to Parkinson’s. It may not. And I’ve dealt with it in the setting of Parkinson’s and I’ve dealt with it just even would change a medication. You know, my neurologist wanted me to change medications from one antidepressant to another that had better anxiety coverage. And I discussed it with my psychiatrist and they agreed, but that two months of changing medications was a temporary and difficult and very challenging depression. I wasn’t showering. I wasn’t leaving the house to do things, I wasn’t eating right. I wasn’t sleeping well. And when you’re in that, it feels like you can’t see the forest through the trees. I mean, I wanted, I felt really, really down. I had the metacognitive awareness to know that it was temporary, but this is hard. And the way I deal with it is to, I mean, there are little things that add up, you know, journaling, having an accountability partner when I’m down, it’s not okay, this is my, for me. I know it’s not okay for me to go three or four days without a shower, if I’m depressed. And so if I need to call Kat and be like, Kat, tell me to take a shower, she’ll be like, Karen, you’re going to feel better if you get in the shower and take a shower and go do your ride your bicycle, it’s okay to phone a friend, you know, but that’s how I deal with it. I hold myself accountable.

Heather Kennedy:

Thank you. Let’s let everybody take a quick bit of this. So Sree, can you go ahead? We just have a few minutes left.

Sree Sripathy:

Sure. The thing I’ll have to say about depression is I think before you’re diagnosed with a disease like Parkinson’s or anything similar, we might often have an idea of what depression is. We often think of it and I’m speaking very generally of extremes because that’s what you see on TV. That’s what you see written about, but depression is not always an extreme. And of course there are people who have the really extreme, really clinical versions of depression. And that is perfectly, I mean, that is there, but there’s all these different types on the spectrum. So there are many times when, you know, I’ve not taken a shower for the fourth day, or I’ve not brushed my teeth for the fifth day and all I’ve done is eat pancakes with syrup every day, knowing I’m not brushing my teeth, that I just can’t find the energy to do anything. And I’m like, oh, that’s not depression. Cause I’m not like suicidal. I’m not this, I’m still engaging a little bit with the world, but actually that is depression. There is apathy there as well. So I think there needs to be a lot more discussion about the spectrum of what depression and apathy look like so we are able to recognize it.

Heather Kennedy:

It can also be anger. And then I’m going to go to Michael because he’s next. Then we’ll go to Kevin, Michael, anything to add about depression? We’ll go to Kevin and come back to Michael. Kevin?

Kevin Kwok:

The thing that we have to be careful is that non-motor symptoms start off as nuisance symptoms, but then they can blossom into something much worse, like depression, which can become crippling. And it’s when you kind of hit that apex, even before you hit that inflection point of when it’s going to be a problem is how you have to address it. And there are no simple solutions. We all have talked about a lot of different things, but I do think mindfulness does go a long way and I’ve actually been able to bring down my depression scores and anxiety scores with true practice of meditation.

Heather Kennedy:

And Michael’s back. Michael, did you want to add anything about depression? Kevin mentioned meditation or I’ve often thought of prayer, whatever works, what works for you?

Michael Fitts:

I’m a believer. So I have a spiritual side to me. I definitely believe in prayer, but I’m also a realist and a what’s the word?

Heather Kennedy:

Pragmatic maybe.

Michael Fitts:

Yeah. I forget where my thought was going. Sorry about that. Oh, okay. So one of the things I think is helpful, sorry about that. One of the things I think is helpful that they have here at my institution and I was actually key to getting it started. It’s really a support group for individuals that have chronic conditions. And so, you know, go into that like every month and feeling like you have like a safe space to, you know, kind of like express yourself, you don’t have to worry about your supervisor being there and being judged because everybody’s dealing with something different. So that kind of thing I think is extremely helpful. Now what’s not helpful is for some reason anxiety, especially in the African-American community, it has a negative stigma on it. And it’s like, and people mean well, once again, they mean well, but it’s like, it’s almost like an idea of like, well, no, you have to stay strong and be like, you can’t cry.

You can’t show any emotion, you know? And then also because the church has to be the center of the community in African-Americans, they always say well go and talk to your pastor, have him to pray for you and don’t get me wrong cause I do believe in that, but at the same time, if you’re doing that and just doing that just by itself, because I think it’s like multiple things that we need to do. So if you’re just doing that, I think that you’re doing yourself a disservice actually. Because you’re not, cause the whole idea is like, I know Kevin mentioned about having a team, but it’s like a holistic approach that you need to take that would be, I think more helpful. At least it has been for me. I can’t speak for everybody, but that’s my take on it.

Heather Kennedy:

We’re getting great feedback from the audience. Now we’re going to go back to Polly as we wrap up.

Polly Dawkins:

Thank you all. Sorry to hop in, in the middle of this really important conversation, it feels as though we have much more to talk about as a group and I’d love to invite you all back panelists and audience to continue conversations as it’s getting deeper, it’s getting more real here, November 18th, we’ll be back if you’re watching this as a recording, sometime in the future, I’m talking November 18th, 2021, we’ll be back together. In the meantime, the team at the Davis Phinney Foundation will send you out an email with the video, with the transcript, with notes, with resources, links from today, and ways that you can get in touch with an ambassador. Look at that. Everybody’s holding their mugs up. So thank you all. Heather, thank you for moderating this discussion. Thank you to the audience for being here. And on that note, I will welcome you all back in a month’s time. Be well, talk to you soon.

Show Notes

- Non-motor symptoms are the symptoms you don’t see in Parkinson’s. Non-motor symptoms vary from person to person and can include but may not be limited to:

- Anxiety

- Apathy

- Breathing

- Cognitive changes

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Dementia

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Hallucinations

- Delusion

- Loss of smell

- Pain

- Skeletal bone health

- Skin changes

- Sleep disorder

- Small handwriting

- Swallowing problems

- Urinary incontinence

- Vertigo

- Dizziness

- Vision changes

- Weight management

- While it is common for people with Parkinson’s to want to hide their non-motor symptoms from their doctors for reasons of self-worth, shame, and feelings of failure, the appearance and progression of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s is natural, and it is imperative to discuss them with your doctor to get the treatment and help that’s available

- Non-motor symptoms can be particularly frustrating because they can’t be seen, and therefore friends and family may say, “You don’t look like you have Parkinson’s”

- Recognize that it may take a team of health professionals to address all of your motor symptoms and non-motor symptoms, because as the panelists emphasize, “One physician can’t possibly address them all”

- Non-motor symptoms such as depression and anxiety can be very difficult to deal with, especially when they arise unexpectedly. Council member Karen Frank encourages people to remain flexible when symptoms like this occur and to remember that no matter how difficult it is in the moment, it will pass and is not forever

- Non-motor symptoms may start off as “nuisance symptoms,” as Kevin Kwok says, but they are important to pay attention to because if not treated, they can quickly blossom into something bigger

- There is no one solution for improving mental health symptoms; these symptoms are often managed through a combination of multiple techniques

- Anxiety is a common non-motor symptom and can manifest in many ways, including an unstoppable stream of worrying thoughts or excessive thoughts on one subject. Council members suggest the following techniques to manage anxiety:

- Practice short, guided meditations

- Split the things you are worrying about into two categories: things you can control and things you can’t

- Establish a support system that you can call when you need to break out of an anxiety cycle

- Utilize a visual or auditory cue to interrupt your anxiety cycle – take a picture, listen to music

- Listen to an old-time radio show or podcast to distract your brain

- Pick up an object and mentally observe everything you see and feel in that object

- Depression is another very common non-motor symptom and can look like many things. Depression for you may be not taking a shower for three days, lacking the energy to make meals, or lacking the interest to do anything. Try one of the following techniques if you find yourself experiencing depression:

- Join a mental health support group

- Explore therapy options

- Talk with your care team about treatments

- Watch a video of a comedian

- Keep a “tickler” notebook

- Call a friend

- Struggling with proper sleep is a common concern for people with Parkinson’s. Our Council members experience a wide variety of sleep issues, including only sleeping a few hours per night, experiencing interrupted sleep, sleeping too much, having worsening symptoms during the day because of lack of sleep, not sleeping deeply, and having sleep disturbances as a side effect of taking other Parkinson’s medications. Their advice is to:

- Keep a sleep journal to observe if there are any specific patterns to your sleep issues

- Structure your day and stop using screens a few hours before bedtime every night

- Listen to white noise as you fall asleep

- Listen to ASMR as you fall asleep (You can find white noise and ASMR recordings on Youtube, Spotify, or Apple Podcasts)

“I try to avoid focusing on the individual non-motor symptoms that I am experiencing, but rather try to address areas in my life that are being negatively affected by them and figure out how I can address those.”

-Kevin Kwok

resources and topics discussed

Health Disparities: Parkinson’s and Cultural Context

Parkinson’s Non-Motor Symptoms Resource Page

I Have Parkinson’s and I’m Okay

Why Is It So Hard to Sleep Now That I Have Parkinson’s?

Depression, Anxiety, and Apathy

Want to Be notified about future YOPD Councils?

The YOPD Council meets on the third Thursday of every month and every session is recorded and shared for all to access. Register for the YOPD Council series here, after which you will be invited to join live and be personally notified when a new webinar recording is posted. Interested in catching up on past YOPD Council webinar recordings? You can find all recordings on a variety of subjects on our YOPD Council Youtube playlist, and don’t forget to subscribe to our channel to be notified when new Youtube content becomes available.