Did you know that dementia in people diagnosed with young onset Parkinson’s disease (YOPD) looks different than dementia in those diagnosed with later-onset Parkinson’s? In this webinar, Dr. Rodolfo Savica, MD, PhD, and YOPD Council Leader Tom Palizzi discussed dementia: what it is, how it develops, and its relationship to Parkinson’s, as well as some distinct differences between YOPD and later-onset Parkinson’s.

You can watch the video below.

To download the audio, click here.

To download the transcript, click here.

Show Notes

- Dr. Savica says YOPD is a completely different disease than later-onset Parkinson’s, biologically, epidemiologically, and clinically

- Biologically, people with later-onset Parkinson’s may experience non-motor symptoms such as constipation, REM sleep behavior disorder, depression, anxiety, and other symptoms up to 30 years before their motor symptoms emerge. On the other hand, people with YOPD often notice non-motor and motor symptoms presenting at the same time, or they develop motor symptoms shortly after developing non-motor symptoms

- Epidemiologically, the presentation of motor symptoms is different. Individuals with later-onset Parkinson’s often present first with tremor, stiffness, and slowness, whereas individuals with YOPD often first notice dystonia, involuntary muscle contractions that often feel like strong muscle cramps

- Clinically, the treatment and management of YOPD are different. People diagnosed with YOPD often have different responsibilities and lifestyles (balancing a full-time job, family, children, and additional societal responsibilities), making the priorities of treatment very unique

- Dementia, generally defined, is the loss of cognitive abilities. Cognition can be split into four domains: executive function, language, visuospatial, and working memory. Dementia can be diagnosed if there is enough loss in even one of the domains to interfere with activities of daily living

- The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s. In Alzheimer’s, amyloid plaques and tangles are built up and cause memory loss in short-term and working memory. Parkinson’s does not involve the build-up of plaques and tangles, but rather the accumulation of Lewy bodies. Lewy bodies can also cause memory loss, but in a way more centered on psychomotor slowing (such as slowness in thinking or difficulty planning ahead or multi-tasking) and visuospatial memory (awareness of the space around you)

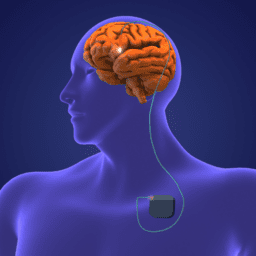

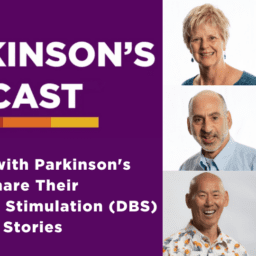

- Certain medications (including ropinirole, branded under the name Requip®), deep brain stimulation, and low blood pressure can actually worsen memory loss, so be sure to discuss with your physician their use if you are experiencing memory problems and/or are exploring their possible use

- The nomenclature used to refer to individuals with young onset Parkinson’s can be problematic, since “young” can vary by person, culture, location, etc. A more accurate way to describe it may be “early onset Parkinson’s,” indicating that the motor symptoms occur at an earlier time than the common age of diagnosis, which is around 60-65

resources and topics discussed

- The Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s

- The Difference Between Lewy Body Dementia, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s

- Deep Brain Stimulation

- YOPD Council: Exercise and Community

- How Important Is Exercise to People Living With Parkinson’s

WANT more advice from our yopd council?

You can register for the entire YOPD Council series here, as well as catch up on recent conversations. We meet on the third Thursday of every month to discuss the unique challenges of living with YOPD.