Here’s a question we and those in our community consider every day: With all of the money that is going toward finding a cure for Parkinson’s, why aren’t we there yet? So, when we had the chance to sit down with Pete Schmidt, a member of our Board and the Vice Dean at the Brody School of Medicine and Associate Vice Chancellor for Health Care Regulatory Affairs at East Carolina University, we asked him this question:

“If replacing dopamine in the brain via Carbidopa/Levodopa helps reduce and sometimes completely eliminate Parkinson’s symptoms, why aren’t we closer to finding a cure? Is Parkinson’s truly caused by a lack of dopamine?”

Here’s what he said:

In 1817, James Parkinson wrote the article that first described the disease, called An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. This essay, and our understanding of the disease from the earliest days until the 1970s, focused on the major clinical symptoms of Parkinson’s that emerge from how the disease impacts the dopamine system, notably the dopamine-producing neurons of the part of the brain called the substantia nigra, which basically means, “black stuff,” named in the days when anatomists just cut up corpses and named what they saw with little (and often wrong) insight.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, clinical researchers figured out that they could treat Parkinson’s with dopamine replacement therapy. Parkinson’s was thus a disease of dopamine and therefore, we could focus on the dopamine system in treatments of Parkinson’s. End of story, right?

Wrong.

Focusing on dopamine for Parkinson’s is like saying that global warming is a problem of temperature. Cooling the air wouldn’t solve the problem of climate change and replacing dopamine doesn’t cure Parkinson’s. Parkinson’s is largely a disease of neurons, and to stop/fix/cure Parkinson’s, we need to stop that disease from making neurons sick.

The neurons are being made sick by being polluted with too much of a protein called alpha-synuclein. This protein seems to principally affect dopamine neurons in Parkinson’s, but as the disease advances, it can harm other neurons, too.

Treating the dopamine system is critical to helping people with Parkinson’s to deal with their symptoms. However, focusing on the dopamine system or other motor features of Parkinson’s is a distraction from efforts to “cure” Parkinson’s.

Why?

As we repair, supplement or prop-up the dopamine system, the disease continues to slowly progress into other parts of the brain. Exercise benefits the whole brain, not just the dopamine system. Therefore, we need more and better treatments that will work as exercise does, not just more and better treatments that work as Sinemet does.

We have many more questions for Pete, and we’ll be sharing his answers with you soon.

About Pete Schmidt

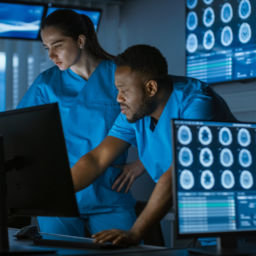

Peter Schmidt, Ph.D. is the Vice Dean at the Brody School of Medicine of East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina, a part of the UNC system. From 2009 through April 2018, Dr. Schmidt served as Senior Vice President and Chief Research and Clinical Officer at the Parkinson’s Foundation where he oversaw research, education and outreach initiatives. Through his tenure at the Parkinson’s Foundation, Dr. Schmidt led as PI the Parkinson’s Outcomes Project from launch through the 10,000th subject recruited, the largest clinical study ever in Parkinson’s disease conducted at 30 academic medical centers. The Parkinson’s Outcomes Project was designed to identify best practices in Parkinson’s care but served as a platform for many other studies.

Peter Schmidt, Ph.D. is the Vice Dean at the Brody School of Medicine of East Carolina University in Greenville, North Carolina, a part of the UNC system. From 2009 through April 2018, Dr. Schmidt served as Senior Vice President and Chief Research and Clinical Officer at the Parkinson’s Foundation where he oversaw research, education and outreach initiatives. Through his tenure at the Parkinson’s Foundation, Dr. Schmidt led as PI the Parkinson’s Outcomes Project from launch through the 10,000th subject recruited, the largest clinical study ever in Parkinson’s disease conducted at 30 academic medical centers. The Parkinson’s Outcomes Project was designed to identify best practices in Parkinson’s care but served as a platform for many other studies.

Dr. Schmidt is active in research, specializing in the intersection between mathematics and medicine, with a special interest in mapping the n-dimensional spaces of clinical data. Schmidt serves as an advisor to several government, industry and foundation initiatives. He has been involved in several national-scale quality initiatives including the US National Quality Forum and the Fresco Network in Italy. Schmidt has recent or current advisory engagements in wearable sensors, telemedicine and remote monitoring and clinical trial design. He has contributed to AHRQ and Commonwealth Fund publications and has been an invited speaker for NIH and diverse international patient and professional conferences. Schmidt previously worked in corporate finance focused on healthcare innovation, created chronic disease management systems and served as Chief Operating Officer of a joint venture of Oxford, Stanford and Yale delivering online education. Educated at Harvard and Cornell, he had a fellowship at New York’s Hospital for Special Surgery.