Less than one percent of people with Parkinson’s participate in research studies. Those who do participate do so for various reasons: the hope of finding a new treatment for themselves or wanting to contribute to knowledge that will benefit others in the future.

Parkinson’s clinical trials, surveys, and studies for Parkinson’s treatments can be as simple as completing an online form or as involved as a months’- or years’-long drug trial. Some trials are observational, where researchers simply monitor participants in their natural state over time. Others are interventional, where participants take a new medication or modify their behavior, such as incorporating a new exercise routine or eating plan so researchers can see how the changes impact their Parkinson’s symptoms.

Because of the great variety of Parkinson’s trials, volunteers from all stages of Parkinson’s are needed. Many Parkinson’s research trials focus on people with early-stage Parkinson’s who are not yet taking medication; this combination of factors allows scientists to study the effect of medication on early Parkinson’s without the influence of other medications. However, plenty of studies rely on volunteers who have been living with Parkinson’s and taking medications for several years, and some studies recruit people who do not have Parkinson’s at all; so, your care partner or others interested might be able to participate in a trial.

When deciding if enrolling in a research trial is right for you, it’s important to understand that although everything is done to ensure the safety of research subjects, the full risks and benefits of experimental treatments being studied are not fully known. That said, without willing participants for clinical trials, important medical therapies would never become available. Every prescription drug used to treat Parkinson’s (or any condition, for that matter) in the US has been tested in clinical trials prior to gaining approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Other countries have similar drug testing protocols to ensure safety.

A potential medication or therapy must clear many hurdles before being approved for use by the public. It must first undergo rigorous testing for safety and benefit in pre-clinical studies. These studies involve animals or take place in laboratory settings. If a compound shows promise in the laboratory, its effect is next examined in humans. Human clinical trials have four phases, which progress from the earliest stage of discovery to testing potential medications or therapies on just a few people to extensive testing in large groups.

The FDA serves as the governing body in the US that approves a treatment if efficacy and safety outcomes are reached in Phase III trials.

The FDA serves as the governing body in the US that approves a treatment if efficacy and safety outcomes are reached in Phase III trials.

Types of Clinic Trials

Open-label study

Open-label studies measure the effect of a treatment, but do not compare its effect or outcome against a placebo. These studies can help determine if a treatment has possible merit. They cannot determine whether a treatment’s benefit (or negative effect) is real or due to a more general, nonspecific effect (called a placebo). A strong placebo effect is well-documented in Parkinson’s studies. Simply expecting or hoping that a medication will help can increase the chance that participants will experience an improvement in their symptoms. Placebo-controlled trials help ensure that any benefits experienced are the result of the medication or treatment being tested, rather than the influence of positive expectations.

randomized controlled trial

A randomized controlled trial randomly assigns participants to one treatment versus a second treatment or placebo. Since the assignment is random and not based on other individual factors, both treatment groups will be similar, which ensures that the trial is controlled for individual influences that can affect outcome (age, gender, duration of Parkinson’s).

randomized placebo-controlled trial

A randomized placebo-controlled trial assigns a placebo to one treatment group, while another receives the active treatment being studied. Participating in this type of trial means that you might not be given the active medication but will instead receive a placebo, an inactive pill or treatment. These studies are necessary because it’s important for researchers to be sure that a benefit is not due to the placebo effect.

double-blind study

A double-blind study is conducted with neither the researcher nor the volunteer knowing whether or not the active pill or treatment has been administered. A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial combines these features and is the gold standard by which new medications are evaluated and approved.

extension study

An extension study is usually an extension of a clinical trial, allowing participants in a formal study to continue receiving the research treatment while it is awaiting FDA approval. This allows for ongoing monitoring of participants and evaluation of symptoms and side effects of the experimental treatment.

Research trials are not for everyone, but they do offer an opportunity to become involved in the advancement of treatment in a careful and controlled manner.

Interested in getting involved in Parkinson’s research? An important next step is learning your rights as a research participant.

Interested in getting involved in Parkinson’s research? An important next step is learning your rights as a research participant.

Your Rights as a Research Participant

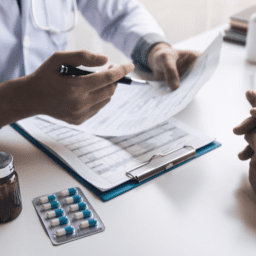

Biomedical research ethics have greatly evolved over the past 70 years, with the primary goal of protecting study subjects. The Nuremberg Code, established in 1948, defined the importance of voluntary participation in research and the requirement of informed consent. The doctor or researcher prepares an informed consent document for the volunteer, which defines the purpose of the research and its potential benefits and risks using plain language. An informed consent document must be read, understood, and signed before any research can begin. Participants may be asked to sign another informed consent document if any details about the study change. Good clinical practice stipulates that research participants should be given a reasonable amount of time to review the document and should have a detailed discussion with the doctor or researcher prior to signing. Informed consents should contain several sections, including:

- Title of the study and names of the lead researcher and sponsor

- The rationale for the study and type of research to be conducted

- Information about the study drug, therapeutic method, and use of placebo

- Selection criteria for participation

- Exact expectations during the study, including procedures, protocols, and study duration

- Review of potential benefits, side effects, and risks

- Alternatives if you do not participate

- Reimbursements, if any

- How confidentiality is protected

- The right to withdraw or refuse to participate

- How and with whom results will be shared

- Who to call if you have questions or adverse reactions to the therapy

In 1962, the US Congress passed the Kefauver Amendment, which required the FDA to ensure that drugs are effective and safe before releasing them to the public. In 1964, the World Medical Association set rules for doctors offering biomedical research to patients. These rules are known as the Declaration of Helsinki. They focus on both clinical and non-therapeutic research and form the backbone of the Good Clinical Practices guidelines used today. Congress passed the National Research Act in 1974, creating the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. This commission produced the Belmont Report, which further defined and solidified ethical principles for research in the US involving humans. The Belmont Report identified three principles that remain in practice today:

- Principle of respect for individuals. All individuals have the right to information and the freedom to decide their treatment. In research, this is ensured by using the informed consent document that outlines the proposed treatment in very understandable terms, stating that the research is voluntary at all times. Individuals who cannot give consent must have a surrogate decision-maker who can best decide on their behalf

- Principle of beneficence. Individuals must be protected from harm. Research should minimize risks and maximize benefits with a clear, understandable explanation in the informed-consent materials

- Principle of justice. The selection of research subjects must be fair

In 1991, the majority of federal agencies that sponsored human research adopted policies regarding the protection of human participants, known as the Common Rule. The Common Rule requires the protection of vulnerable patients (i.e., prisoners, children, pregnant women), requires appropriate informed consent, and sets standards for institutional review boards (IRBs), the conduct of research institutions, and record keeping. While researchers and doctors must conduct themselves ethically, patients must also follow through on their commitment to allow for the most accurate data collection when a new therapy is under consideration, in order to protect individuals who may use the therapy in the future.

These rules help ensure that research is conducted in a humane and respectful fashion and maintains the highest level of safety possible for participants of research trials.

These rules help ensure that research is conducted in a humane and respectful fashion and maintains the highest level of safety possible for participants of research trials.

How to get involved

Everyone who has benefited from Parkinson’s medications has others in the Parkinson’s community who took part in clinical trials to thank. Many of our Ambassadors and friends who have been clinical trial participants say that although the results may not benefit them directly, the future value for so many others is immeasurable. Consider participating in a clinical trial and help researchers continue their work to discover a breakthrough that could delay, slow, or even reverse the effects of Parkinson’s.

To explore trials happening now, visit the National Institutes of Health’s clinical trials website and fill out their “Find a study” box, or visit foxtrialfinder.michaeljfox.org and fill out their “Find a trial” box and create an account to find clinical trials in your area. You can also find more of the latest Parkinson’s trials, surveys, and opportunities in our most recent “What New in Parkinson’s” article.