While most things are said out of a place of good intention, as a person with Parkinson’s you may have had some hurtful, insensitive, or irritating things said to you. In this YOPD Council session, our panelists discuss some of these moments in their life as well as what you can do to educate, advocate, and improve understanding.

You can watch the video below.

The YOPD COuncil is back in session!

After a brief break from regular council meetings over the transition to the new year, the YOPD Council is back! The Council meets on the third Thursday of every month and every session is recorded and shared for all to access. Register for the YOPD Council series here, after which you will be invited to join live and be personally notified when a new webinar recording is posted. Interested in catching up on past YOPD Council webinar recordings? You can find all recordings on a variety of subjects on our YOPD Council Youtube playlist, and don’t forget to subscribe to our channel to be notified when new Youtube content becomes available.

You can read the transcript below or download here.

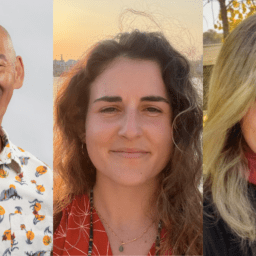

Heather Kennedy (YOPD Council Leader, YOPD Women’s Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation):

We’re gonna have some fun today talking about a few things we’ve heard people say to us are y’all ready? Did you put your chin straps on?

Sree Sripathy (Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation): Right here.

Kat Hill (Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader, YOPD Women’s Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Who’s gonna kick it off?

Heather Kennedy:

I heard a great one this morning. I’m ready.

Kevin Kwok (Board of Directors member, YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation): Go for it.

Tom Palizzi (Ambassador, YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation): Do it.

Heather Kennedy:

My doctor or a doctor, I should say, in response to me complaining about something that was very serious, very, very serious to me said, are you seeing a psychiatrist? That’s always fun. You know, in other words, you might be crazy because we’ve done everything right over here on our side. Wouldn’t it be awesome if everyone’s ego in the medical community was equal size to their compassion? I wish that for everyone. Moving forward, what do you got Kat?

Kat Hill:

I’ll tag onto that. One of my favorites is, oh, I know what you mean. I know how you feel. It’s one of my least favorite things to hear whether we’re talking about Parkinson’s or not, because it shifts the focus away from whatever that other person’s feeling and making it about one’s self. So I think in trying to be compassionate, sometimes our loved and people that genuinely care about us, say, I know how you feel. And I don’t always feel like that’s compassion.

Kevin Kwok:

I would agree with that completely. It’s almost like it’s all about me in a deflection rather than really listening to you. I mean, they are automatically go to, well, I have a hang nail too, and it really bugs me every day. You know, it’s just one of those deflections, which means that you can’t really tell your story no matter what symptom, no matter what aspect of the disease you talk about. Like the famous one I always get is I really have a problem with fatigue and insomnia and noise here. You bet, you know, I got the same thing, I was up all night last night and it’s just right away.

Robynn Moraites (YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Well, akin to that, one of the ones that I had is it’s almost code for, I don’t wanna hear it, which is everybody’s got something. And you know, yes, that is true. Right? Everybody over a certain age probably has something, but Kevin, I like your hangnail metaphor. Not everybody has something as serious as Parkinson’s.

Michael S. Fitts (YOPD Council Leader, Davis Phinney Foundation):

Well, I actually, let me piggyback on that. I actually had a physician tell me, oh, everybody has a tremor nowadays. It’s like, oh really?

Kevin Kwok:

Or the other way around. It’s like, I don’t see a tremor, you must be fine.

Tom Palizzi : Yeah.

Heather Kennedy:

That’s like, I’m not hungry, there’s no starvation.

Sree Sripathy:

I had someone that I mentioned, who found out I had Parkinson’s, I mentioned it to them and they looked at me and I won’t mention gender because they might be listening. But they mentioned oh, well, you know, I have eczema and that’s really tough.

Kat Hill: Mm.

Sree Sripathy:

And I thought, Okay, thank you for sharing that. And you know what? Just to support the people who do have eczema, it is tough to have eczema, no denying that. I know people who really struggle with eczema, but I, whatever the response is, the response I would’ve liked is, oh, that sucks. I’m so sorry, how are you doing, versus telling me what you have. I don’t need to know what you have in that moment.

Kat Hill:

Has anybody heard that, oh, but you look so good.

Tom Palizzi:

That’s just the one I was gonna say, you get that a lot. You say you have Parkinson’s and they say, but you look great, and you’re like, well, how did I look before this?

Heather Kennedy:

And you’re like, thanks???

Sree Sripathy:

But you know, that doesn’t bother me, honestly, for me, that doesn’t bother me so much. I’ll tell you because people don’t know what someone with Parkinson’s necessarily looks like. And that’s what we’re doing with the YOPD council. We’re changing that. You can’t always tell, right? So, changing the face of what Parkinson’s looks like is really important. So that doesn’t bother me so much. Give me another year. Maybe it will.

Tom Palizzi:

It’s mostly humorous.

Kat Hill: Michael?

Michael S. Fitts:

Yeah. That question actually bothers me somewhat. And it’s pretty much for the same reasons, like what is a person with Parkinson’s supposed to look like? And I just don’t get it.

Kat Hill:

Yeah. Maybe they’re thinking the little old men crept over, you know, that we’ve seen so often in the assessment with the little cane. I mean, that seems to be a lot of the stereotypical, you know? And none of us here fit that, right?

Tom Palizzi :

Well, I don’t know. I can make that look pretty good these days.

Kevin Kwok:

On that same theme, when you exercise, right, I mean, we all know that exercise is our mainstay. And to hear people say, oh, I can’t believe you just rode that bike. Or I can’t believe you just ran that race. You must be fine. Or you must be getting over your Parkinson’s.

Tom Palizzi:

Yeah, that’s one of my favorites as well. I mostly get this from people that I’ve known for a long time. And they’ll always ask, well, how are you feeling? Are you getting any better?

Heather Kennedy: Oh, no.

Tom Palizzi :

You know, for me, that’s just a teaching moment to say, you know, look, it’s a progressively degenerative disease and progressive does not mean the positive, progressive means it’s getting worse. So no, I don’t get better, but I’m not getting as bad as I could. That kind of thing. So, it gives me an opportunity to explain to them why exercise is important to Parkinson’s, why, what we eat and how we behave and our attitude and all these other things that we do as strategies to keep ourselves, you know, in good enough shape to do things like this and everything else we try to do in everyday life.

Heather Kennedy:

You are such a classy guy.

Robynn Moraites :

Tom, I didn’t handle it very well when I was newly diagnosed, but I had some well-meaning friends that didn’t understand anything about Parkinson’s and every time we spoke on the phone, they would say, how are you? And I finally just told one of my best friends, I said, stop asking me that. What do you want me to tell you that my thumb is twitching more today than it was on Wednesday? And she’s like, well, I was just trying to be a good friend. I was like, well, stop.

Kat Hill:

It’s not working.

Robynn Moraites :

Yeah. And so, I didn’t handle it very gracefully while I was coming to terms with my own diagnosis. And I ended up sending an email out to friends and family, you know, when I realized what was going on and that people didn’t have any point of reference, frankly, other than Michael J. Fox, they didn’t have any other reference. I sent a big email out explaining, you know, I’m not dying tomorrow. I’m gonna be living with this for a long, long time. And I am busy living a, you know, a busy and hassled life, just like you. So please don’t treat me any differently.

Michael S. Fitts:

Yeah. You mentioned something that’s related to something that I always hear. So I have a tendency, especially being a person of color to ask individuals, do they know anybody that has Parkinson’s? And so, I usually get, oh yeah, my grandfather had it, but he died.

Heather Kennedy:

It’s like, what do you do with that?

Michael S. Fitts: It’s like, why would you say that to me? I wouldn’t say that to anybody.

Kevin Kwok:

I hear the other way, Michael is like, oh, my uncle Bob lived with Parkinson’s for 30 years and he did fine. You’ll be fine too.

Kat Hill:

And again, those kind of comments I think are said to make them feel more comfortable. That we’re really okay. But I, Robynn, I did what you did. I sent an email to friends and family saying, listen, I don’t want Parkinson’s to be all we talk about every time we connect. I’m happy to answer questions or to check in, but I don’t want it to be like this other person in the room every time we’re talking. And let’s just keep it that way. And I promise to be upfront if you ask me a direct question, you know, how are you feeling, how are the symptoms or whatever. And it almost gave them permission to not have to bring it up. And I think that was good.

Sree Sripathy:

Yeah. I had a friend of mine. Oh, sorry, go ahead. No, I had a friend of mine recently. We were on WhatsApp, FaceTime, whatever video call. And she said, oh, you know, your head is doing something weird. Why is it shaking like that? And I love this friend dearly. She’s been my friend for decades and she knows I have Parkinson’s and I’ve sent an email. I’ve explained it. She’s very familiar. And yet her way of saying that was like, okay, I just didn’t know, I didn’t even know how to respond to that. You know, I just told her, well, it’s dyskinesia. Oh but yeah, but it’s a bit weird. It’s odd. Why is it doing that? And I’m just like, you know, maybe you should just, and I had to call her up later and say, you need to be really careful with the way you say things, because I’m pretty tough in many ways, but you saying something like that was really blunt and it made me feel very self conscious.

And I didn’t wanna actually talk to you after that or be on a video call with you. And then of course my dyskinesia got worse, cause I was like, and then my tremor became worse and you know, and all of that sort of thing. And I’m just wondering how can someone who is so sensitive and so aware in so many ways just have gotten it wrong. And these are just, I can’t be mad at her, but it’s just a constant path of educating people. Even people that you think would get it. And sometimes it’s exhausting. It’s just exhausting.

Heather Kennedy:

And there’s something called kinesia paradoxa, it’s a phenomenon we see in Parkinson’s disease where we experience these severe difficulties with movement because we are upset usually, you know, it’s part of the whole process. And I remember Mike, my radio show co-pilot from the YOPN Mike and Mike radio show. He said someone was getting brain surgery and then a guy could walked up to him and said, did they get it? But it was DBS. So, it’s like, people think it’s going to be cured. They’re hoping it’s gonna be cured. Or they’ll say something like, but there’s lots of research out now, there’s cures right? Like I heard it on the news.

Kat Hill:

And they’re close, they’re close to the cure, right?

Kevin Kwok:

I hear that all the time. And you see this study in lemurs in readers that digest. I read it and I know there’s a cure around the corner.

Robynn Moraites :

Well, and I think it’s important here to do what I call listen for the love, that people are grasping to try to make themselves and us feel better. And they also try to ascribe, they try to explain the inexplicable or ascribe meaning to it. And some of the most hurtful comments I’ve had have been around trying to ascribe meaning to it. Things like it’s God’s will, or, you know, on the Judeo-Christian end of the continuum, you don’t have enough faith. And on the new age continuum, well, your soul chose this for this incarnation. And that kind of puts the locus of control in me, in self. And the reality is, it isn’t. And it is a thing that we all have to deal with, but I try to listen for the love underneath cause people sometimes say really ridiculous things, very well intended and well meaning. Sometimes I have to do translations.

Kevin Kwok:

You know, speaking of love, you know, my own mother gave me the most backhanded insult the other day. I was going through my divorce and she said, oh, Kevin, I just spoke to my friend. Her daughter is recently divorced too. You should reach out to her. You know, you’re a good catch with the exception that you have Parkinson’s, right? I was like, whoa, wait a minute, Mom, I’m an exception because I have Parkinson’s.

Heather Kennedy: Ouch.

Kevin Kwok:

I said that that really hurt me to the core because when your old family members say that, they mean well, but they’re trying to kinda soften the blow.

Michael S. Fitts:

So how about, how about nonverbal questions? And I guess you know what I mean. So, I’m gonna give you an example. So, you might be interacting with somebody and they might know you have Parkinson’s and they’ll come up to you and say, well, I thought that all people with Parkinson’s had a tremor or something like that, the other thing is they don’t really say anything, but the look on their face and it makes you feel self-conscious. So, I’ve been tremor free before in a situation. And because they were looking at me kind of oddly it made my tremor come out even more. So, there’s still those nonverbal things, cause an expression can get you every time.

Kat Hill:

Yeah. It’s like you’re being tested.

Heather Kennedy:

And they’re looking at you up and down like…

Michael S. Fitts:

So let me jump in one more time because you just reminded me of something. I guess when I first got diagnosed or whatever, I maybe I didn’t look like I had it, but it was, I almost felt like the Parkinson’s people were kind of like judging me and it’s like, well, what are you doing in here cause you look so different because everybody in the room was white and older. And so, they they’ll be like, oh, we thought you were the speaker. You don’t, you know, you don’t look like you had Parkinson’s that kind of thing. Which makes me really, really self-conscious and nervous.

Kat Hill:

I have heard that a lot. I guess, you know, you don’t look like you have Parkinson’s, how can you have Parkinson’s?

Robynn Moraites :

Or how can it be so bad, look how well you’re doing.

Michael S. Fitts: Right.

Robynn Moraites :

Like what are you complaining about?

Michael Fitts: Right.

Robynn Moraites:

That’s so hard with the non-motor symptoms, how much affect our quality of life, and yet, you know, if my tremor is calm, everything must be great.

Kat Hill: Yeah.

Sree Sripathy:

I had a doctor, a movement disorder specialist mentioned to me early on in the disease that I didn’t look like I had Parkinson’s she couldn’t tell. And I didn’t have a lot of obvious symptoms then. So, I was like, oh whoa, maybe I don’t have it. Maybe I’m the lucky one. Maybe I’m progressing so slow. It’ll only hit me when I’m 80. And then if she were to see me now, like three to four years later, I’m like, yeah, no, you can probably tell, you know, with the dyskinesia and the dystonia and many things. But I think for me, that’s the hard part, when people say you don’t look like you have it, there’s this moment of like, oh maybe I don’t have it. Like I fall into that little delusional thinking, still going back in my mind

Kat Hill:

Into the river of denial.

Sree Sripathy: Yeah. Yeah.

Heather Kennedy:

That was one of my favorite things someone ever said to me, I was in a support group when I first joined and I kept asking about diversity and they accused me of race baiting or whatever language they used. And all I was saying was, hey, where’s the diversity here? We’re all a bunch white people sitting around talking. This disease doesn’t discriminate. What’s going on? I was literally just coming into a support group for the first time going, where are all the people of color? And they said, you don’t even have Parkinson’s.

Tom Palizzi : Ooo.

Heather Kennedy:

And I was like, with all my heart, with all my heart. I wish you were right.

Tom Palizzi :

I’m cured. I’m cured. Thank you.

Heather Kennedy:

Thank you man to the leader of this support group who just kicked me out for asking a really simple question.

Michael S. Fitts:

Right, and that’s a legitimate question too.

Heather Kennedy: Right?

Tom Palizzi : Definitely.

Heather Kennedy:

They were furious with me, anyway.

Kat Hill:

They probably wouldn’t have liked your jacket today, either Heather.

Heather Kennedy:

Right? They probably wouldn’t like Brandi Carlisle either then.

Kat Hill:

We love your jacket.

Tom Palizzi :

Those of you that are watching today feel free to pop your favorite questions into the chat. And we’ll pick up on those and we can play this game together. So, I just wanted to point out that you can join the conversation.

Kat Hill:

Has anybody else? Oh, go ahead.

Sree Sripathy:

I was saying, you know, if we don’t have any bad, horrible stories, what about, maybe we can switch not right now, but what is one of the nicest or the best things someone has said to you in terms of Parkinson’s, maybe towards the end.

Tom Palizzi :

Yeah. Sometimes it’s actions more so than our reactions to certain things like I typically board flights early with the folks that are impaired because as it comes closer to getting on the plane, I start to go downhill. Cause I get nervous. So that gets real challenging. So, I’m walking around the airport looking pretty good, cause I have Parkinson’s and then I go to get on the plane and I start freezing and stuff like that. So, I try not to carry luggage and baggage with me, but as I get on, and I froze one time, really bad. I was stuck there and just staring at this guy, he jumps up out of his chair and he’s like, he gets in my face and he says, what are you looking at? And I’m like, I can’t move. I’m frozen. He’s like, what are you talking about? I’m like, I’ll explain in a minute. Can you please take my bag?

He took my bag and put it up and I said, I’m really sorry. I didn’t mean to offend you in any way, but I have Parkinson’s and one of the things that happens to us is we freeze. In other words, I can’t move. And he sat in front of me, but he came later on as the flight went on, he sat next to me. He says, I want you to tell me more about this thing that you were talking about, with Parkinson’s, and I explained to him, and he told me that his dad had Parkinson’s or had been diagnosed. So, things like that are my favorite situations where you can turn it successfully into a teaching moment as I call it, or a moment where you can actually, you know, pivot on what was bad to something that’s really good and bring somebody else along and help them understand it. So.

Heather Kennedy: I love that.

Tom Palizzi : Yeah. It’s great.

Heather Kennedy:

Tom. That’s what we live for. We’re like, I’m an activist. It just so happens. I’m an advocate. Here’s my info. Let’s talk.

Kevin Kwok:

How many you drive with a handicap placard? I pulled once into a parking space and the guy growled at me and said you’re not disabled. That’s for disabled people.

Heather Kennedy: Same.

Sree Sripathy:

You know what? I’ll bring a cane with me if that will help people. I mean, it’s good as protection too. I’m sure.

Michael S. Fitts:

Exactly. So, have you all had to do something? I call it playing the PD card. You know what I mean when I say that? So ordinarily I would not do it, but this is a situation I was in and it was funny because I was on my way to, I think it was a Michael J. Fox patient council meeting. And I was just having this horrible day and I had misplaced my keys and it took me so long to find my keys, I missed my flight and then they were trying to tell me that they couldn’t reschedule me and all this kind of stuff. And so, they were like, okay, you can call this number and let them know what your situation is. And so, I called the number and I had to tell them that I did have Parkinson’s and you know, I had to go with that. I kind of felt bad, but at the same time they were gonna either charge me like for an extra it was an obscene amount of money to get another ticket or they were gonna let me through. So, the playing the Parkinson card, that one time did work.

Kevin Kwok:

I played the Parkinson’s card to Disneyland. I was with my kids. It was a holiday weekend. It was the most crowded day in the park. And I went up to guest services and said, I have Parkinson’s, I don’t look it like it, but I have it. And they said, well, you and your family can go in this line and go right up to the front. And my kids afterwards said, dad, it’s so good that you have Parkinson’s. Remember that at Disney world.

Heather Kennedy:

I love it. I was just thinking of Jimmy Choi’s story. After Tom mentioned the flight and of course Disney, someone was on a flight next to Jimmy and he says, is it catchable? Jimmy’s like, I’m sorry, what? Do you not have access to modern media? You know and this thing called like Google search engines, you know? But it was a fascinating conversation after that because Jimmy being the classy guy that he is, he was chill with it. I would’ve been like, get outta here. Can I get a different seat? You know, like, you know, but you guys took the time to, you know, it was great.

Kat Hill:

How many of you experienced the have have you tried questions?

Robynn Moraites : Oh yes.

Kat Hill:

Try a cinnamon pack on your feet at night, you wear socks over them. Have yeah, what are some things people have recommended?

Heather Kennedy:

Michael? What you got going on over there?

Kat Hill:

Yeah, you’ve got some clicking going on.

Robynn Moraites : You’re on mute Michael.

Kat Hill:

Have you tried? No, just kidding.

Michael S. Fitts:

Sorry about that. So I have, okay, so this is actually a part of Parkinson’s. So, I have a hard time sitting for extended periods of time. So, I have this desk that kind of like raises up. So that’s what I was doing. Sometimes I have it where the camera is gonna cooperate and I don’t have to move it all over the place. But this is obviously not one of those days.

Kat Hill:

Of course, since you’re on camera, that’s how it works.

Heather Kennedy:

Have you guys ever switched it where you thought you weren’t on camera? So, you were like doing something, like picking your nose or something and then you go to turn it off and you’re like, oh…

Michael S. Fitts:

I’ve done that with a mute button too.

Sree Sripathy:

Fun fact. Picking your nose is harder with Parkinson’s disease.

Heather Kennedy: Yes!

Sree Sripathy:

And you have to do it more often and you have to do it more often. Just throwing that out there. All I have to say.

Kevin Kwok:

Thank you for that information.

Clean contact is also a challenge. Don’t even bother.

Kat Hill: Oh.

Michael S. Fitts:

Oh, I’ve got one. So I was doing a, participating in a clinical trial, it had something to do with like vision and maybe exercise or something. So, I had to go to an ophthalmologist or what have you. I assumed that he knew that I was in a study or whatever, and you know, knew what my condition was, but he said to me, I’m gonna need you to be still, sir. I was like dude, I can’t be still. So, of course that made it worse. When I tell you, and I’m not a violent person, but when I tell you I wanted to knock him out.

Heather Kennedy:

Like, come here, I’ll show you still.

Michael S. Fitts: Exactly.

Kat Hill:

Yeah. Yeah. I’ve heard that at the dentist. And he sometimes forgets that I have Parkinson’s and then he always apologizes, you know, and I’m nervous, you know, the drill’s going, it’s coming closer and my head’s shaking more.

Tom Palizzi :

I cannot keep a straight face when someone asks me to hold still, that just cracks me up. And that’s probably my favorite to laugh back at.

Heather Kennedy: Right.

Kat Hill:

I usually say if only I could, if only I could, I would.

Sree Sripathy:

One of my cousins told me I should get a part-time job at McDonald’s as the official milkshake maker, since that machine is always down. Like the machine is always broken, but you could just hang out there and just shake away. And it would be great. Like thank you.

Heather Kennedy:

I was thinking of all the dumb things I’ve said to people.

Kat Hill: Ooh.

Heather Kennedy:

I remember walking up to a woman and asking when she was due. She wasn’t pregnant.

Michael S. Fitts:

Yeah, I’ve done that too. I never do that anymore.

Heather Kennedy:

Well, I was young or how about the time when I walked up to somebody who was working for a major organization in Parkinson’s when I was first diagnosed, and she was shaking a little bit this way. And I had asked her a question. So, when she did this, I said, no, what do you mean no? And then I’m like, oh my God, I can’t believe I did that. So, it’s like, we all do dumb things, which is like Robynn mentioned, like people she’s looking for the love, like people really do mean, well, it’s very, very rare somebody’s gonna say something on purpose to try to like hurt somebody. They’re just, they’re sort of like deer in the headlights. They don’t know what to say. And they immediately look at you with pity. Like, ohhh, and I’m like no I’m good!

Sree Sripathy:

But that’s said, I think sometimes the people, if we are unfortunate enough to run into them, the ones who are deliberately cruel and mean may not hurt as much. This is just, I’m just throwing this out there. Cause you already know the type of person they are or where that’s coming from. It’s these subtle things that people say unintentionally that can be like, oh, that was painful where they didn’t mean to be hurtful. And how do you respond to that and educate that? Or do you just drop it? That’s something I struggle with. For example, my mom whom I love dearly. She’s one of my closest friends. She still struggles to accept that I have Parkinson’s, it’s been, you know, I’m going on to my eighth, you know, obvious year, I guess, maybe seventh after diagnosis. And she says, look my hands shake too all the time. Maybe it’s just that. And she means it so endearingly and so sweetly. But I honestly don’t know how to respond to that. And I have other people who, a few of them who do something similar, and they mean well, but yeah, I struggle with that essentially is what I’m trying to say.

Michael S. Fitts:

You know, I was in a situation when I was I can’t say when I first got diagnosed, cause I waited a minute before I told my job and my family, but actually my father was in town and he wanted to meet for dinner. So, I met him at the restaurant and I noticed that he had a tremor. And so, when I noticed that it actually gave me the courage to let him know that I had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s. The ironic part is, oops. Oh that’s my mom, actually.

Heather Kennedy:

It’s hard to be popular.

Michael S. Fitts:

Okay. Sorry about that. Yeah. I should have had it turned down, my fault. So that actually gave me the courage to like let him know and oddly enough he does not have Parkinson’s he just has a tremor, but I found out fairly recently too, that his oldest sister, my aunt, has Parkinson’s, so it’s just really, really interesting. So how long did it take you guys to tell your job or your family?

Robynn Moraites :

Well, I told my family immediately and ironically enough, the last couple of years, my mother’s now been diagnosed with Parkinson’s and now that she knows the full constellation of symptoms, she’s convinced that my grandfather, her father had it and was never diagnosed. So, we know we have it in the lineage, in our family, but I’ve only recently started telling my work because I got deep brain stimulation in 2020. And I told my boss, but I was keeping it very close to the vest, but I give a lot of live presentations. I speak publicly a lot and it’s getting harder and harder to hide my symptoms and medication is just getting less effective. And so, I’ve started having to tell and I have a very public position across the whole state. A lot of people know who I am. It’s the only reason I’m willing to do this now is because I’m out of the closet at work.

But I told a friend who I do consider to be a friend and it’s like I have to do the translation in my head because I know he meant well, but he said, well, if anyone was gonna get Parkinson’s, I’m glad it was you. And I know that that’s not what he meant. I know what he meant was if anyone could fight this thing and not just, you know, collapse and surrender to it, if anyone could fight, you have the fighting spirit. I know that that’s what he meant, but that’s, it’s not what he said.

Kat Hill:

Yeah, I’ve heard that a lot, oh Sree, go ahead.

Sree Sripathy:

No, I was just gonna say Robynn to your question, I told my family, I mean my parents and my siblings immediately within like the first two to three days, there were other people that I told as well that I felt, I thought I felt comfortable telling. And I actually kept a list of the date and the name of when I told each person, you know, because I’m a huge list person. I love that. And I will tell you about 90% of the people I told I regret telling because they didn’t understand, the response wasn’t what I maybe would’ve expected. And it just actually made me feel a lot more tender and vulnerable in telling them. And so, when I actually came out of the closet, so to speak, mine was in 2020 and I came out on Facebook that I had Parkinson’s disease and purely for the purpose of doing advocacy, cause that’s, I think it was 2020 or 2021, I’m honestly not sure, but it was during the COVID pandemic.

And my parents were not happy with me at all that I did that. They were quite upset and they said why do you need to air out your private business in public? And why do you need to tell people? And I had to explain to them, you know, and I still have to explain to them, and I know many cultures and many people face this as well. It’s not just, you know, limited to one, one region of person, but I said, it’s for advocacy. People need to know that someone there out there looks like me, south Indian, you know, American, female, young, brown, diagnosed, who’s working full time and trying to fight this disease. So, I think that’s important and it’s still a struggle to kind of get them to understand that I’m public about it. You know, they’re still not comfortable with that type of language, but yeah. Sorry, long response.

Michael S. Fitts:

Oh no, that was good. I’m glad I’m not the only one that used the term, I came out on Facebook, cause I did that too. And, I tell you what happened, I don’t know if this happened to you all, but you know, told the date that I was diagnosed and kind of like a little bit about the situation, how it happened. I got flooded. My inbox got flooded with things, with people saying, oh, you’re so courageous. And, you know, you’re doing well. You don’t look like you have Parkinson’s, but you’re doing well and all that kind of stuff. And people were coming and telling me that, oh, you know, I don’t have Parkinson’s, but I have an essential tremor or, oh, I deal with such and such. And that actually was an encouragement to me. And it kind of like jumpstarted my advocacy because I’m an extreme introvert, but this condition is actually given me I guess some encouragement and courage to like speak to people because people really are out there looking for somebody that they can relate to.

Heather Kennedy: Right, right.

Tom Palizzi : Definitely.

Heather Kennedy:

And that way you’re in service.

Michael S. Fitts:

Absolutely. And the best part of it is with my advocacy, it takes the pressure off me, the spotlight off me. And I don’t have time to feel sorry for myself. Cause I’m focusing on somebody else.

Heather Kennedy: You have a purpose.

Michael S. Fitts: Absolutely.

Tom Palizzi :

But that helps. That helps a lot to have a purpose for sure. And I think when I was diagnosed, I told you know, my family right away, my wife and my kids, but I also told my business partners almost immediately because the position that I was in left me such that they needed to know, because I knew after reading about after getting my PhD in Parkinson’s overnight that I was gonna go downhill. And I didn’t know how fast at that time, but we all agreed that, you know, we’d pay attention to it as partners, business partners because I knew someday I’d have to leave or step down or whatever. And I lasted a long time working, but when it was time to go, they all knew, we were all comfortable with it. And I knew, I knew that was my, it was my choice. I could have stayed, but I decided to go. And because just being away from that level of stress really helped lift me back up into the, you know, have abilities to do these kinds of things, for example. So, I’m a big believer in telling people right away, cause it, again, gives you that opportunity to explain to them what it’s about. And that’s sort of your first step in advocacy, really, is helping those folks around you understand what’s going on.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah it’s a big relief weight off your chest when you come out. But I went for years without telling people, sending people ahead to meetings. So, I wouldn’t have to walk with them on the streets so they could see me. And I was really glad to finally come out, but it did change everything once I did come out right. You know, the good assignments didn’t quite come my way. And the client work that was high visibility shifted. So it’s not an automatic it’s not every situation is easy for everyone to come out right away.

Kat Hill:

In my circumstance, you know, I was working, I was a director and a full scope practitioner at a busy inner city or city hospital, delivering babies and medically legally, it was not okay for me to stay and work, once there was any question about my ability to do my job. And so, Parkinson’s that was a really hard thing for me. I’d worked really hard and was kind of at the top of my career and I really grieved that loss hugely. And, like, I’ve heard others say stepping away from doing 24-hour call in a high stress arena. And it took me some time, but rest helped a lot of my symptoms after a while. So, I do think it was the right decision. It was very difficult at the time. And I feel like you, I found another way to be a midwife to people that are newly diagnosed or being able to be of service in other arenas.

But I think if you’re newly diagnosed and you’re out there and you’re feeling a little bit of that loss, I think you also have to really feel it for a while. I think you have to grieve what you thought it was all gonna be like, and we’re talking about what people say and they wanna help you. They wanna care. It’s looking for the love again. And I loved that, Robynn, I’m gonna use that. And I think accepting that people, whoever with any new diagnosis or big life shift, just listening to people and letting them talk about their process is really a gift. So, if you’re out there and wondering what to say, sometimes you just have to show up, bring a cup of tea and put on, you know, your good listening ears, what I, and listen to what it’s like for that other person. And maybe not try to find a solution cause as we all know, as of today, there isn’t really a solution to offer. That would be my advice.

Robynn Moraites :

I like what Heather put in the chat about using too much energy to kind of keep it a secret and tacking onto that, when I was first diagnosed, I was very, very in the closet about it. And I found, I felt such a sense of isolation because at its basic, I wasn’t being my most authentic self with people. Not that everybody’s entitled to know every bit of my business, but I felt like there was this like Plexiglas wall between me and other people because maybe I was trolling a pin in my hand and I knew why I was trolling that pin, but they didn’t and it just was incredibly isolating. And so, for me it’s been a gradual kind of coming out of the closet. I feel like politically for my job, I had to do it the way that I’ve done it. But it definitely feels more authentic and integrated.

Sree Sripathy:

Yeah. I, number one, Kat, that was a beautiful way to put that, what you said, and then in speaking to what somebody else said, I think Robynn mentioned this about work. You know, I got laid off for my job. And not because of anything PD related just because the company was getting rid of everybody. And then I was totally fine letting everybody know about my PD, cause I’m like, I’m not going back to work. I’m going to be an artist and a writer and photographer and make, you know, 300,000 a year being a poet, which is completely rational. Okay. Completely rational. And then I realized for me, with my Parkinson’s and my brain and some ADHD, this is not healthy. So, I started looking for a job and I thought, oh my God, this is the first time I’ve had ever had to look for a job and let people know I had Parkinson’s, how do I do this?

And my old boss at my company knew I did the entire upper-level team supported me, but what I was, you know, I mean, I have it on my LinkedIn profile. Parkinson’s advocacy, Davis Phinney. It is on there. So, if anybody looks at it, you know, they will see that. And I, my current boss, I told him, I keep checking in with him. You do know that I’m doing Parkinson’s advocacy. Right? You do know that, is that okay? And he said, you know what? As long are getting your work done, it doesn’t matter which I’m very blessed, but just really quickly, last thing to speak to what Kat also said about you’ve had to suffer enough sometimes and accept what you’ve lost. And sometimes it’s the big things. But yesterday for me, it was not being able to fold the recycled brown paper bag from Panera that held my chocolate croissant. I could not fold this bloody thing and put it in the recycled bag. It drove me nuts. And I thought something I could have easily done in two seconds now is taking me two minutes of concentration. And I thought it’s just a freaking brown bag. And I just got so sad and then I had to eat more chocolate croissants. So.

Heather Kennedy:

Then you had another bag to contend with. One of the greatest poems that I enjoy lately is called, “The Shoe Lace,” by Charles Bukowski and it starts out, you know, it’s not the big things that send you to the mad house. It’s that stream of indignities, those humiliating little things, you know, like the broken shoelace when you’re running to get somewhere across the street, it’s just constant with Parkinson’s. We’re like the princess and the pea, everything bothers us. And we can’t really do a lot. It’s like being in peanut butter or wet cement that’s drying, right? What does it feel like to you guys? Like what does Parkinson’s feel like?

Tom Palizzi :

Yeah that’s a, it reminds me of something my wife used to always say when we were raising the kids, she’d always say pick your battles. You know, if he wears an earring or she gets a tattoo or whatever, how big a deal is that? But with Parkinson’s, Sree, you get to your point about folding the bag, you know, in the morning, I can’t do hardly anything for about an hour until the meds kick in. So, I’m trying to make coffee, trying to make myself something eat for breakfast. And it’s just one of those things where, well, I’ll just throw this stuff away later, cause it’s gonna take me 20 minutes to get to the trash can and back to the coffee and I gotta have coffee first. So, it’s like, it’s hard enough to do that. But those are the kinds of things that I think about like in the general context of this, what you shouldn’t say to someone with Parkinson says is what, I ask myself, why is this taking you so long? So, stop asking yourself, just pick your battles and go with the flow and make the coffee.

Heather Kennedy:

Time to make the donuts.

Kevin Kwok:

Yeah, I had something to mention, I just went on disability and I heard someone say that, oh, I was so lucky. I won the lottery. And I’m thinking like, I would give anything to still work and not have this disease. That’s not a lottery, you know, winning.

Sree Sripathy: Wow.

Tom Palizzi :

That’s a really good point. Kevin, I think some people confuse private disability insurance with welfare and they’re not the same thing. We don’t do the, I don’t do the welfare thing. I’m sure you guys don’t either per se, but I opted to go with social security early as well because…

Kat Hill:

And we’ve earned that. We’ve earned that our whole working lives.

Tom Palizzi :

Right. Well, more importantly, it helped me get onto Medicare cause when you’re not working and I was 56 years old, but there’s penalties to do that too. Right. So, I mean I’m locked into that rate. So I can’t go any farther, but you know, those are financial things we learn how to manage. But again, that’s one of those kind of painful things that people will say to you, oh, you’re living on welfare now, you’re living off my tax rate. And I’m like, well, not really. So.

Sree Sripathy:

It’s almost like somebody tells you, I mean, hey, you’re so lucky to get that handicap card. Yeah. Thanks, to go to Target and shop. Absolutely.

Robynn Moraites :

Well circling back up to Sree and Kat’s discussion about losses. A collateral loss that I wasn’t expecting because I didn’t know was a side effect of DBS is I lost my ability to swim laps in a pool. And I’m from Miami, Florida where I grew up swimming constantly. And it’s not like I’m some super competitive swimmer and I can swim, I have read actually side effects studies where people from Australia jumped in the water and drowned because nobody knew it was a side effect of DBS. But what I find is that I can swim. I mean, I can be in the water and not drown, but the repetitive motion, if I have a really good arm stroke, my legs aren’t kicking. And if I have a really good kick stroke, my arms aren’t going and I can’t coordinate that. And I got back into the triathlons last year, thanks to the Davis Phinney Foundation. But that’s where I discovered that I, you know, I’m coming in last in the swim all the time now when swimming was like my best event. So, and that was a surprising loss and in some ways it hurt more because I wasn’t prepared for it. It felt like out of the blue. And I’ve heard it said that Parkinson’s your world becomes kind of smaller and smaller. And I felt like that was one of those things that happened that just really caught me off guard and created a surprising emotional response in me.

Michael S. Fitts:

So let piggyback on that for a quick second. So, do any of you find yourself a lot more sensitive than you were before? Like and mine goes on the extreme, sometimes I’ll just be watching TV or a commercial or something and I will just burst out and start crying. I’m like, what is wrong with me? And then the other thing is I go into these laughing fits. Sometimes the things that I’m laughing at are kind of like inappropriate, but I can’t help it. I can’t stop it. It’s just odd to me.

Kevin Kwok:

Michael, that’s pseudobulbar effect.

Michael S. Fitts: It’s what now?

Kevin Kwok:

It’s called pseudobulbar effect. And there are some companies looking at making medications for that, it’s uncontrolled laughter and crying in sometimes inappropriate places.

Sree Sripathy:

It’s interesting. Cause we have this facial freezing that happens and then we have inappropriate laughter you it’s like Parkinson’s is this weird dichotomy. I thought I was crying all the time at hallmark commercials or McDonald’s commercials cause my niece after my nephew was born. I mean, it’s just like, I never cried before. And then after he’s born, I cry all the time, but that was right before I got diagnosed. So, actually, but that was years before I was diagnosed. So, I’m not sure if it’s the same thing. I still think it’s because he was born and I’m like super aware and sensitive about everything. But the one thing I’m more sensitive about is light and sound. I find it so hard to adjust to loud noises and chaos, a bunch of kids running around, parents talking loudly. You know, my family is very loud and boisterous. I mean, and I never thought I was until I went to my sister’s house recently and I told him like, why are you guys so loud? Why is the TV always on, why are the lights always on? Why are you always talking? And she just looked at me and I’m like, oh my God, something has changed in me. This is not how I used to be.

Kat Hill:

It’s all neurologic stimulus, right? What we hear, what we’re trying to manage in the chaos. It impacts us differently. Our neurologic systems aren’t working the way that everybody else’s are. And I think that’s important for other people in our world to know that, you know, I have been sort of the opposite of Michael. I’ve been like a lifelong major extrovert and I was the one that hosted all the parties and did all the planning for kids. And I just can’t do that anymore or I can’t do it the way I used to. And if I choose to do some of it, I don’t feel very good. The noise and the chaos, the trade off is too great for me. And that, you know, Robynn talking about the loss of the swimming and it’s incremental loss that we’re dealing with and aging is partly that, right. But, with Parkinson’s, there’s this accelerated part and this neurologic part and it’s, I think we have to accept some of it, grieve for it, and then try to get to the next step before the next one happens right?

So, and that’s hard for people that are loving us and trying to be supportive. That’s the part that gets hard to navigate, you know, and why are you so down? Or why are you late again? Or why is that so hard when you could do that last month? Or, you know, it’s just different. And I don’t know that I have an answer to that, but what do you guys tell people, you know, about that progressive, you know, loss that little bits at a time?

Sree Sripathy:

I told them, I wrote them all a letter when I first got diagnosed, letting them know this is what to watch out for that was years ago. Now I need to do an update, but in particular, one friend of mine, she sends long text messages, like email texts. And I had to tell her, I cannot process that anymore. I can’t. Please break them up into small paragraphs for me, if you break or send me an email, because I always would pride myself on being “joom” I could just pick up everything, everything, and I’m still pretty good, but I’m thinking, why am I pushing myself to be how I was before? I just need to tell people, can you please work with me on this, three sentences, stop, space, space. You know, and it’s worked fine. Yeah.

Robynn Moraites:

Well, and Heather puts this organizing incoming stimulation as an issue for most of us. And it’s such a simple thing, but I was doing a meditation sitting yesterday for 20 minutes with my partner. And we were in his living room and he has a computer set up and one of the drives was doing a backup. And it’s almost this imperceptible sound that I don’t even think registered for him. And I was like, this is my meditation where I get to practice, just accepting what is, and I get to accept the fact that this is driving me bat shit crazy. And when we were done, I was like, can you please turn off that drive? And it took him like a second to even hear the drive. He’s like, oh, it’s doing a backup. And I’m like, yeah, I need it to stop. And it was just this little pitter, pat sound of a drive. And it was driving me and it’s like, how do you, and I said to him, it’s affecting me neurologically I can’t explain it other than that. And I don’t know how to explain it. I just have, you know, eight other people here sort of nodding their head that they get it.

Heather Kennedy:

We can’t walk and chew gum at the same time. Notice when you go downstairs, you can’t have both your hands full, you have to count the stairs. Have you ever noticed when you try to do that walk in the morning when you trip, and you’re kind of falling on the floor just to get to the bathroom. But if you take big steps and focus and ground yourself and gather yourself, you have a better chance of not falling it’s because we can’t jockey too many things at once.

Michael S. Fitts:

I have my challenge with my depth perception. One of the worst things are, I have to be extremely careful when I’m going down a flight of stairs, because I’ll think I’m about to step on the floor and there’s like one or two more steps. And I end up falling and I’m so thankful that I haven’t really hurt myself pretty bad. Cause that used to happen a lot. It’s kind of subsided. Then the other thing is I cannot park my car. I’ll think that my car is straight and all the way close to the wall or what have you, I get outta the car and my car is like twisted. Like I just can’t, I can’t do it.

Robynn Moraites :

I had that parking problem before Parkinson’s, but now it’s really bad, Michael. I didn’t know it was Parkinson’s related. I thought it was just my parking skills.

Heather Kennedy:

We’ll have to blame it on that.

Kevin Kwok:

People think I’m one of those Asian drivers and I’m saying no, I’m a Parkinson’s driver.

Tom Palizzi :

There’s another thing that’s really curious with Parkinson’s is having lost my sense of smell for years now. One of the scariest things people ask me is, do you smell that? Oh my, I just get horrified. I’m thinking, oh God, I hope it’s not me.

Heather Kennedy:

Has anyone ever told any of you that you’re inconsistent? I laugh and laughed when a new Parkinson’s patient told me that, I’m like, you just wait.

Sree Sripathy:

I had a friend who told me that. She said, I don’t understand why sometimes you just sleep all the time, but other times you’re awake for hours. And yet when I need you, you’re not there because you’re asleep always when I need you. And I’m like, oh man, how do I explain fatigue and sleeplessness? And I mean…

Kevin Kwok:

Or worse yet you were fine five minutes ago or half an hour ago or yesterday. I get that all the time. It’s like, you know, they don’t understand the ebb and flow of the disease. And it’s hard to explain that, you know, yesterday I could ride 10 miles on a bike. And today I’m a bubbling idiot walking across the floor, right?

Heather Kennedy: Yes.

Sree Sripathy:

It’s like the weather, we’re like the weather.

Heather Kennedy:

Such uncertainty. How do we manage uncertainty?

Sree Sripathy: Chocolate croissants?

Heather Kennedy: What’s that?

Michael S. Fitts:

I always tell people I’m just taking it one day at a time.

Kevin Kwok: That’s good.

Heather Kennedy:

Okay. Favorite things that people have said or worst things you’ve ever heard. Is there anything?

Sree Sripathy:

I’ve got a favorite thing to wrap up. Favorite thing is when I said, God, I don’t know whose gonna take care of me when I get sick. Cause I don’t want anyone to do it. I wanna be able to do it myself, but what if I can’t? And two of my friends completely unexpected said, we’ll be there for you. We’ll change your diapers. We will do everything. That was, made me cry. Still makes me cry. Yeah.

Tom Palizzi : Bravo.

Kevin Kwok:

One of the things that I’ve heard is from fellow people that say that, you know, all the cool kids seem to have Parkinson’s, I’ve never met a Parkie that I didn’t like.

Michael S. Fitts: That’s interesting. OK.

Kevin Kwok:

I get that a lot.

Tom Palizzi :

I read one this morning to wrap up a conversation. One of our fellow ambassadors here at the Phinney Foundation said, I didn’t pick Parkinson’s but I picked this group. So, all you out there, all my colleagues here on the screen, we keep a pretty good family here. So, if you need anything, let us know.

Kevin Kwok:

We take care of each other.

Heather Kennedy:

We are really fortunate to have Davis Phinney foundation too, to live better now.

Kat Hill:

Live well today.

Sree Sripathy:

And Polly, you can send any chocolate croissants you want to Kat and she’ll get them to meet. Just throwing that out there, circling back, circling back.

Polly Dawkins (Executive Director, Davis Phinney Foundation):

You all are wonderful. Thank you for sharing your experiences. I’ve just been sitting here in the background, laughing, and smiling and a little tear in my eye a few times. Thank you.

To download the audio, click here.