Parkinson’s can affect nearly every system in your body and may touch nearly every aspect of your life. So, it’s no surprise that understanding sex and gender differences and how they impact Parkinson’s is an important consideration for living well.

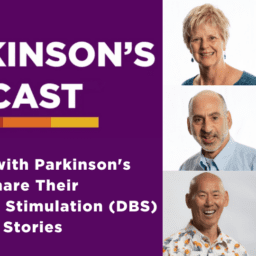

This webinar focuses on issues experienced by men living with Parkinson’s and includes information and opinions shared among panelists Allan Cole, PhD (professor UT/Austin), Danny Bega, MD (urologist), Michael S. Fitts, MS, Arun Mather, MD (urologist), and Kent Toland, MD (urologist, retired). The panel discussed a variety of topics, including:

- Common concerns and challenges

- “Plumbing” issues

- Erectile dysfunction

- Medication strategies

- ON times vs. OFF times

- Reconciling self-image

- Professional transitions, accommodations, and career modifications

You can read the transcript below or download it here.

Melani Dizon (Director of Education, Davis Phinney Foundation):

My name is Melanie Dizon. I am the director of education at the Davis Phinney Foundation, and I’m really excited to be here today for the super important conversation on men and Parkinson’s. We have an incredible line up of speakers with so much insight and so much expertise. I’m gonna turn it over to Allan Cole. Allan is one of our absolute favorite people, person, friends of the Foundation. He’s done a lot of webinars with us, and he very graciously agreed to be the moderator for this panel, and we love having him. So, Allan, I’m gonna turn it over to you and I’ll be in the background if anybody needs anything.

Allan Cole (Professor, Steve Hicks School of Social Work):

Great. Thank you, Mel. And thanks to the Davis Phinney Foundation for all of its good work. And for offering this opportunity today, to talk about a number of important things that impact men in particular, but really impact all of us who live with Parkinson’s in different ways. So, I wanna say thank you on behalf of the distinguished panel that I’m going to ask to introduce themselves here momentarily. Really our goal today is to talk about some of the challenges that men with PD face, but also some of the resources that are available to help meet some of those challenges. And we’re just gonna have an organic conversation and see where it goes. And so, let’s dive right in. We have an hour, a lot of ground to cover. So, I’m gonna ask our panelists to introduce themselves and maybe include just what your connection with Parkinson’s is. And I’m gonna ask Michael Fitts to start us off.

Michael S. Fitts (Assistant Professor and Assistant Dean for user access and diversity, University of Alabama at Birmingham):

All right. Thank you everybody. I appreciate the opportunity to come and speak to you. My name is Michael Fitts. I am 49 years old. I got diagnosed with Parkinson’s back in 2011 at the age of 38. I’m still working at the University of Alabama Birmingham. So, I’m just trying to maintain and keep myself busy and keep myself healthy and strong.

Allan Cole:

Thanks, Michael. Arun, would you go next?

Arun Mathur (Urologist and Medical Director of the Surgical Program, Lakeridge Health, Ontario):

Sure. So how, what’s my connection? I have a 24-year connection with Parkinson’s disease. Many of you guys probably know my wife’s online presence, Dr. Soania Mathur. My wife developed Parkinson’s disease not too long after we got married, 24 years of age and she sorry, 27 years of age. She’s had it for 24 years and that’s my link into Parkinson’s. I am a staff urologist still practicing, but a lot of the physicians and patients in the area knew my connection with Soania and my understanding of the disease and therefore the neurologic side of urology in my practice grew quite significantly. And I work just outside of Toronto, Canada.

Allan Cole:

Thanks Arun. Danny, would you go next?

Danny Bega (Movement Disoders Neurologist, Northwestern Unviersyt Feinberg School of Medicine):

Sure. My name is Danny Bega. I’m a neurologist specializing in Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. I’m at Northwestern University in Chicago. And I spend most of my time taking care of patients with Parkinson’s disease, primarily as the most common movement disorder that I see in my practice. A lot of my focus has been on some of the non-motor features of the disease in particular and ways of managing them using a combination of both medication and non-medication options has sort of been an area of interest of mine. It’s always a pleasure to work with the Davis Phinney Foundation. And thank you for having me here today.

Allan Cole:

Thanks Danny. Kent?

Kent Toland (Retired Urologist and Person with Parkinson’s):

Hi everybody. I’m Kent Toland. I live in Portland, Oregon. I’m a retired urologist, I’m 63 and diagnosed with Parkinson’s at age 54. I have another connection to Parkinson’s. My father was an obstetrician gynecologist diagnosed at about the same age and forced into retirement as well. So, I come at it from a little bit different, unique perspective. And honestly, if I didn’t have Parkinson’s, I’d be practicing urology till I was 70 or 80. I loved it. So back to you.

Allan Cole:

Thanks Kent. And I’m Allan Cole, again, I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s about five and a half years ago at the age of 48. I live in Austin, Texas, and teach at the University of Texas at Austin. So, my first question is actually for the physicians on the panel, and it is this, what are some of the more common concerns or challenges that men with PD raise with you in your practice and what kind of guidance do you tend to offer them? Yeah Danny, why don’t you go first.

Danny Bega:

Sure. I would say first of all, the most common concerns that are raised are probably among all my patients, not just among men, is people want to know about, you know, what can I do to slow down progression? What can I do to impact the course of this disease? And a lot of the times with men who have been particularly active much of their life, it’s wanting to know how to maintain that high level of activity and exercise. If they haven’t been, if they’ve been sedentary, it’s how do I get started on you know, we always talk about the importance of exercise. So how do I get started and do, what’s the right kind of exercise for me and what should I be doing? And then I would say the majority of the time in the clinic while motor symptoms obviously come up and we address them at every visit, I would, I’d say by far the most common concerns I get are related to some of them non-motor issues, particularly concerns about what’s gonna happen to my cognitive abilities and my level of independence.

And sometimes that’s from the person living with Parkinson’s, sometimes that’s from the partner. And some of the mood related issues like anxiety, anxiety comes up frequently and sleep problems. I would say those are some of the issues that I see on a daily basis.

Arun Mathur:

So, for me, it’s a little bit different. I mean, as a human plumber most of my issues are plumbing related. So, patients that are referred to me usually come in primarily broken down to two camps. There are people that are progressing more rapidly in the older age group that feel that this is something tied to the Parkinson’s, you know, the frequency of urination, getting up at night to pee, slower stream, et cetera, in the daytime. And they’ll tie it to that saying, okay, I gotta get in to see somebody and the family doctors often, or sometimes even the neurologist having trouble dealing with that will forward them onto us. The other part half is the people that have a little bit milder Parkinson’s symptoms, and they’ve got 200 men in their social group at the local guys club who all have VPH issues, prostate enlargement, and have prostate problems.

And well, God, my symptoms sound just like John’s prostate problems and Frank’s prostate problems. So, they come to me thinking it’s a prostate related issue, which is understandable at people in their fifties, sixties, and seventies age group, only to find out as we start digging into it a little bit deeper. No, it’s your Parkinson’s that’s the root cause or possibly, and is often the case, a combination of both contributing to it, erectile dysfunction seems to be less of an issue coming into my doorstep. I dig into it after they’ve come to see me about their urinary issues, which is a bigger bother. And there’s that whole host of reasons why erectile dysfunction seems to play a little bit more of a backseat role for people in their, especially the older age group, the sixties and 70 and 80 year olds that have PD because they have so many other things on their plate. That’s less of an issue for them. That’s how they present in my practice.

Kent Toland:

And I would echo what Arun said about referral, you know, the patients I saw with Parkinson’s were those referred with incontinence problems primarily and certainly a reticence to talk about ED or sexual dysfunction and not necessarily referred for that, but always anxious to, you know, if the subject was brought up, it kind of opened the door for them to talk and be a little bit more frank about their disease process.

Danny Bega:

That’s interesting. I would just say obviously I’m kind of seeing the full spectrum of Parkinson’s disease and then I’m referring to urologists to manage a lot of these specific issues that you both raised, you know, we have, it’s our kind of practice to have like a checklist of questions so we don’t forget to ask about certain things and erectile dysfunction, urinary issues have had to become part of that checklist because I have found that often there’s so much that people want to cover and ask about that either that gets put not to the front of their list and so, they don’t bring it unless I ask or there may be some embarrassment or whatever reason they don’t wanna ask about or feel comfortable asking about it. When I started to ask about erectile dysfunction you know, it’s a yes, no, on my checklist and it’s come up very frequently, particularly in the younger men who have come in with Parkinson’s or even preceding their diagnosis of Parkinson’s.

And seeing that there’s likely a connection there. If you ask about it, it tends to come up more. And the urinary issues also, you know, when we ask about that, that frequently comes up and trying to figure out on our end, we’re as neurologists not qualified to be able to this determine if this is this a prostate issue, is this Parkinson’s related issue. So, we often then have to send them to urologists to figure that out because also a lot of people are in the age group where they could have prostate issues that could be contributing. So, I think it’s not just the person living it with, that’s not sure if it’s Parkinson’s related or not, but sometimes the neurologist may not be sure.

Kent Toland:

I think you hit on a really important thing. You have to ask the question and you know, in my experience, that again, opened the door for people to talk and be a little bit more frank. I always thought it was a really interesting specialty, I chose a surgeon who is almost a part-time psychologist. I felt like a lot of what I did was counseling, and you know, guiding people through some pretty personal issues.

Arun Mathur:

Yeah. I think the whole concept of referring on is important, Danny and Kent can probably attest to that. If it’s a Parkinson related issue, the methods of treating it, which is neurologic based or neurogenic bladder are gonna be quite different. You know, you get into your beta three agonists or anticholinergics and the certain class of drugs, that class of drugs really doesn’t work that well on DPH. So, if we think it’s all PD and happens to be a big bulky prostate, we’re kind of going down a bad pathway by giving the wrong drugs, which can either give more trouble to the patient, more issues of holding back urine, urinary tract infection, other problems, or we just keep saying, hey, your symptoms getting worse. I think the PDs getting worse. Versus the other direction, we start treating them like a family primary care physician, or the neurologist treats them with BPH drugs, puts them on Flomax or some other drugs or a Avodart to shrink the prostate. And the whole time that’s doing nothing, their symptoms are getting worse from the PD. So, I think it’s important to, they need to be assessed properly to see which of the two camps they fall into or both, in which case we try to do combination therapy going forward.

Allan Cole:

Yeah. So, I was gonna talk about erectile dysfunction third or fourth, but we’re already there, so let’s stay with it. Sounds like it’s a fairly common experience for those of you treating folks with PD and other age-related sort of conditions. How do you, in lay terms, how do you start sort of figuring out is PD driving this or the medications that a person’s taking for PD or is it mostly age related or is it a combination? How do you sort of assess that and what would you want, you know, folks with Parkinson’s or their care partners to know as they’re coming in and talking with you about this thing that they may be reticent about speaking of?

Arun Mathur:

I can start, I guess. To answer your first part of your questions. Yes, yes, yes, and yes. Most often I find it’s a combination of all those things. A big part of my practice is the older generation population. So, they’re gonna have preexisting some level of ED anyways. And that’s often vasogenic based, you know, narrowing the blood vessels, et cetera. But then you couple onto that huge issues on top of that, you have the dopamine side of it. So, you know, the lack of dopamine can also exacerbate the issues with erectile dysfunction. Along with that, you have huge movement issues. You know a lot of these guys become very self-conscious that they can’t move their body around the way they used to in order to help perform. And that can include fatigue, include pain, include dyskinesias, dystonias, all these things which kind of compound it from the psychological side.

So those two kind of hand in hand mixed together and exacerbate it. I also see you asked about the care partners, big issue, no question about it. When you have somebody coming in who’s been looking after their husband for the last, you know, X number of years and we know that for a number of biological and psychological reasons, women, as they get older, do have challenges in sexuality. And then you exacerbate that with the whole issue of taking care of somebody and you’re fatigued, taking care of somebody as a care partner. And then you also have issues with also you see them dyskinetic, how do you connect with that person emotionally, or intimately when they’re moving and dyskinetic, you think, okay, they’re in pain. How can I form a sexual bond at that moment of intimacy?

So, they have their issues. You have huge sleep issues. You know, these patients have insomnia and sleep problems, which again, compound into the erectile dysfunction. So, unlike, the standard patient that comes in with erectile dysfunction is essentially unlike pre-master in Johnson’s days, it used to be in the sixties and fifties, we thought 90% is in your head, 10% is actually organic. We’ve now reversed it. We found that 90% is organic based with plumbing or hormonal or electrical problems. Only 10% is in your head. I would say with Parkinson’s, with all those issues I mentioned on the psychological and depression on that side, the non-organic side of it plays a huge role, meaning non plumbing related. So yes, they have narrow blood vessels.

So, they have probably associated diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, but you couple, all those Parkinson’s issues. And then I’m almost gonna say it’s close to 50/50 the two of them mixing together causing significant erectile dysfunction issues. And then that then plays into the relationship both on the care partner side, who’s exhausted, sleep deprived in that process. So, you gotta tackle it on multiple fronts to try to take care of it. I don’t know what the rest of the team’s views are on that.

Allan Cole:

Well, how treatable is it? That’s one of the questions in the chat, you know, is this something that folks have to just accept or are there often ways to treat it?

Arun Mathur:

I think that there’s many ways to look at it. So, unlike a regular patient that comes in, if I’m just gonna throw them some Viagra, Cialis, no, that’s not gonna work here. That might help bypass some of that 50% organic I said, with a narrow blood vessel and they could probably get an erection a little bit stronger, but it’s irrelevant if you can’t start that intimacy moment, it’s irrelevant if you can’t kind of tackle some of the fatigue and the other issues. So, I mean, optimizing your PD drugs, you know, get them and find the sweet spot when you’re ON as opposed to OFF like trying to have an intimate moment when you’re OFF or dyskinetic or dystonic, well, that’s a colossal waste of time. So, find the ON times. Often, that’s first thing in the morning, you know, by the end of the day, you’re exhausted.

And I see that in my wife, I should not be talking about my wife about that in this channel. She’d kill me. I hope to God, she’s not watching, but with my wife also, it’s tougher late in the day and evening when she’s exhausted and in more OFF periods versus first thing in the morning after good night’s sleep. And we know sleep revives the dopamine stores in the body, what little they have, that’s a good time to hit it. If you have relationship issues and you have burnout as a caregiver, definitely seek a sex counselor that can help out, try to be, I mean, there’s populations, in older populations, Allan, and, you know, without getting too graphic, it’s the old-fashioned one-on-one missionary way of going about things. There’s a, and I’m not gonna go into details, but there’s a lot of variety in which you can express intimacy. So, experiment a little bit and then talk between the husband and wife. If you don’t have communication, and you’re constantly frustrated with everything, you’re gonna kibosh it right from the starting.

Danny Bega:

I just wanna emphasize the point about the optimizing the timing, because this is true for any physical activity. And sexual activity included is making sure that you’re doing your best to do that activity when your medication is working optimally, because it really does make a difference. And that’s something that your neurologist should be able to address with you is kind of paying attention to the timings that are, where it is that your medication seems to be failing or working best and then kind of arranging your day as much as you can around that and then optimizing that, what we call ON time, that time that the medication is giving you its intended benefit. And using those times. The one other thing that I do think should be mentioned is with medications that are used for erectile dysfunction, like the Viagras and Cialis, the one thing that I do warn people to just pay attention to with Parkinson is in Parkinson’s there’s this problem of autonomic dysfunction, which is that that automatic part of the nervous system that controls the blood pressure and the blood vessel regulation, the dilating and constricting of blood vessels that controls our blood pressure and blood flow.

It is often impacted in a negative way. At any level in the disease, it can be affected. And as a disease becomes more advanced, we tend to see more problems with that system. This is why sometimes people with Parkinson’s, as they get older, can start to have feeling faint dropping their blood pressure when they stand up. And so one of the things to watch out for with those drugs is that they can dilate blood vessels. They can cause drops in blood pressure. And so, one thing I would just remind patients who are using those drugs is just be careful with standing up suddenly if you’re using those medications because your blood pressure could drop, you could feel faint. And so that’s just something to take extra precaution with with those medications.

Kent Toland:

And just to check in a little bit here if I could. So, you know, you’ve heard the science from two practicing physicians. I’m 10 years out, so I’ll leave it to the experts now you know, to get right down to the subject of how it makes you feel 10 years into this. Parkinson’s sucks. It’s a terrible emasculating, de-masculating, and feebling illness that chronically progresses and it’s a drag. So I think what has helped me and I’ve experienced erectile dysfunction now at the eight or 10 year mark is feeling more self-esteem by being in shape. It’s like the cancer patients that I would have in practice, patients with prostate cancer, what’s gonna kill them is not their prostate cancer, 99% of the time it’s their heart or vascular disease.

And so, my mission when I was diagnosed was to get on a bicycle and lose 30 pounds and ride my bike and get to feeling better about myself. And I think that’s a, that, you know, it is multifactorial, obviously there’s decreased sexuality, you know, endogenously related to Parkinson’s, but there’s, and there’s, exogenous, you know, side effects from medications. But I think one of the things that is really empowering about dealing with these problems is getting back to, you know, sharpening the saw basically, getting your physical fitness back and feeling stronger and able to, you know, walk forward.

Arun Mathur:

That’s a really good point Kent, because that is huge in a lot of the attraction issues, whether you like it or not, self-attraction to the other partner and just a physical act, it’s a very physical act and you’re struggling to do the simplest thing sometimes with the tremors and dyskinesias, and if you lose that strength component it makes a big difference. I mean, we talk about exercise, good for the vascular flow to the penis anyways, from erection point of view, but from completing the act and carrying out the act and being intimate with a partner, that exercise component I think is massive. Yeah.

Kent Toland:

And Allan, I’m sure you’re gonna get this. Maybe I’m interrupting you. I think it’s critical to involve the partner. Because I think men as a rule go to physicians and don’t speak up, don’t really address these issues as, you know, in a forthright manner the way women might. So, I always had for consultations with patients with ED, I always invited and encouraged the significant other to be there and you know, sharing this, sharing what I know and being a urologist has been huge for my relationship. Also, a sense of humor is so important.

Allan Cole:

Well I appreciate all the expertise and the candor and getting right down to what I know are a lot of questions on people’s minds because they’re coming in on the chat, I’m gonna, push off of this just for a little bit because we have, you know, more ground to cover, but we’ll see if we work our way back, but one of the challenges that I face and Kent, you alluded to this just a few moments ago and I know I’m not alone in this because a lot of my friends in the community have expressed similar kinds of feelings and experiences is really how was I gonna reconcile my self-image or my understanding of who I was as a man with my sort of pre-diagnosis self after I was diagnosed. In other words, being diagnosed called into question for me, a lot of, sort of fundamental questions of identity, who do I understand myself to be? You talk about emasculating, and you know, what does it mean to maybe lose some of your physical capacities over time? And that was a real struggle for me. And I know it is for a lot of people. So, Michael, I’m gonna put you on the spot and maybe ask you if you have any experience with that and sort of how you leaned into that.

Michael S. Fitts:

So, thank you for that. I’m gonna talk about it from a couple of different ways. So, prior to my diagnosis I was having problems, I’ll just put it out there masturbating. So, if I’m having problems masturbating, that made me kind of wanna jump up and go to the doctor because I’m like, this is not gonna work. So, I did do that and it was embarrassing, really, and had no idea that it was tied into, you know, the Parkinson’s, but I’m so glad I did that because I probably would’ve got diagnosed later. It’s just one of those things that’s kind of like, you know, you feel self-conscious about it and it’s about your body image and your self-worth and all of that stuff. So, one thing that makes it challenging for me too, is the fact, and I’m single and I don’t have a partner.

And so, I did go to a urologist and ordinarily, I probably would’ve never done this, but I mean, it was a serious problem. The whole, I guess, dopamine thing and not able to control how you move and all that kind of stuff. So, the thing about it is being a single person, you have a different aspect and a different way to go down that road. So, it’s like when you’re trying to date somebody, how soon do you tell the person that you’re dealing with, you know, Parkinson’s disease, you don’t wanna scare people off, but at the same time, you know, you don’t want them wondering like what’s going on, why is he, you know, jumping around and fidgeting around or whatever he, something is obviously, you know, wrong with him. So, I did go to a neurologist, I mean, a urologist and got a prescription.

And the thing that I was telling him was the fact it was different because I didn’t have a, you know, a steady partner because I kind of felt like, okay, if I take a pill, Viagra or Cialis, and I’m not knowing for sure if I’m gonna have sex, I kind of feel like that I’ve wasted, I’ve wasted, you know, some medication. And so, I was sharing that with the urologist and the other thing he told me, you know, he would say, well, you could go down this route and get injections. And you know, that doesn’t really sound pleasant at all either. So, all of a sudden the medicine started working better when I heard that injection part, you know, I kind of got my second wind, but the thing about it is he did change my medication and the thing that I appreciate about that is it, it happens to stay in your system a little bit longer than I guess, Viagra. So, it’s not like I have to have, you know, it’s not like I have to take the medication and have to have sex, you know, within 24 hours.

But that’s a really tricky thing when you’re trying to navigate through that, you’re already experiencing all this other stuff, and this just adds on to it. And it really is a psychological, you know thing too. It doesn’t help with your anxiety. It doesn’t help with your depression. All of it to me is kind of like tied into, you know, one big lump of, you know, mess. And it’s really, really hard and challenging to kind of like, you know, navigate through that, especially when you don’t want to, you don’t want to admit it.

You know, like I said, it’s an embarrassing thing, but one thing I can say about being diagnosed with Parkinson’s, it has really, really help me as far as like being more transparent because on one end, I’m going through this stuff, on the other end, as far as like my advocacy is concerned, I don’t want anybody else to go through this and I wanna be able to assist, you know, in some way. Obviously I’m not a physician, but you know, this one conversation, you know, could be beneficial to a lot of people that are, you know, embarrassed to go and ask their physician about that. But that’s what the physician is for and you should utilize all of the resources that you have available to you.

Allan Cole:

Yeah. Thank you, Michael. I really appreciate that. Kent, do you have any perspective on that as a person with Parkinson’s?

Kent Toland:

The perspective of…?

Allan Cole:

The identity piece, reconciling your sort of post diagnosis self with your pre-diagnosis self?

Kent Toland:

Yeah, I think all patients who are diagnosed with Parkinson’s male or female, there’s a lot of identity and what you used to do. I shared earlier with our other urology colleague that I used to do robotic surgery and was, you know, very capable and you know, lost all that. And, you know, I think it’s important then to develop a new sense of who you are. And it helped me and my wife to go to a therapist and we still occasionally will pop in and see this person for a touch up or whatever. But involving your partner and what you’re going through is critical. Because they’re going through it too, identifying yourself as a patient with Parkinson’s who is also a grandfather, a father, a son, you know, you’re more than what that diagnosis tells you are. And so again, part of me changing and, you know, wading through this morass and progressing, as Parkinson’s does, it’s been you know, critical to sort of redefine myself. And I think exercise is just paramount in that and that’s how I got involved with Davis Phinney and hopefully will continue to stay involved.

Allan Cole:

Yeah, I think, well put, you know, for me, it’s reminding myself that, you know, a disease doesn’t define me, doesn’t have to define me, it’s part of who I am, but there are many other parts of who I am that can be developed even as I’m maybe losing some of my functioning with Parkinson’s. And I think just to put a bow on this sort of strand of the conversation, I think Parkinson’s is really a disease of loss, right? It’s really, you know, a series of significant losses over a long period of time for most of us. And I think it’s important to name that because, you know, everybody, whether they have PD or not experiences loss and how we sort of adapt to those experiences and in my case, trying to find ways to you know, use those for developing other aspects of my life I think is a really important thing for us to be thinking about, but as important to be sharing with one another.

And that leads me to sort of a next question, or maybe an observation into a question. I, this is a generalization, there are always lots of exceptions, but my experience has been that many men find it difficult to express their feelings, to talk about their fears or their worries, or their anger or their sense of loss. And especially sometimes to other men. And at the same time, we know that that’s precisely what is beneficial for really all of us who go down that road. And so, I wonder what all of you would say about the value of people with Parkinson’s, their care partners, those who love them sharing more honestly, and with candor, the kinds of things that we’re talking about today, what do you think about that?

Michael S. Fitts:

So, providing more educational opportunities like this is today, I think that’s really key. And some people just need to hear some people just need to hear that, and that’ll kind of get them, you know, more comfortable. Like I said, that’s a part of my advocacy work is because I know that people are having, you know, struggles, you know like I have, or, you know, similarly to other people, but it’s that whole piece about getting them to communicate about it. And I’m not saying it’s an easy thing, but it’s really necessary. That’s the purpose of us having support groups, so you can actually get people in a room that kind of like have light situations and might have been a little, you know, apprehensive to bring that up. But when you’re in a group, individuals that you can kind of relate to, I think it just does, it’s a great thing. Not saying it’s easy, I know it’s difficult, but it’s a necessary thing to communicate.

Arun Mathur:

I would echo that Michael and I’d also like to add another piece to it. I would look at it from a slightly different angle and that’s as a care partner. Okay. And so, from my point of view, I think we need to do more to involve care partner in understanding the disease, both the, you know, biological side of it, but also the non-biologic side of it. And Kent had alluded to, and Michael alluded to, the buzzwords, like feeling emasculated and the sense of self-worth sense of attractiveness. Well, who are you feeling attractive to? It’s your partner? And, you know, I see that multiple times where my wife is either OFF and we’re trying to have an intimate moment. I hope to God, my kids don’t watch this webinar, but trying to have an intimate, I have three daughters, so they don’t wanna hear this, but trying to have an intimate moment and suddenly either before or during or after, around that time, she goes OFF, she goes dyskinetic, because she took too much of her Sinemet or something else.

And then the first thing in her mind, I can see in her eyes is I look ugly. I look hideous. I’m not attractive. I’m not sexual. He’s gonna not like this. He’s not gonna like me. And so, my job is is trying to reassure her and make her feel that, hey, you are attractive. I still find you attractive. I’m not, you know, PD is a part of you. I’m not gonna ignore it. It’s not like it’s something I’m gonna shove under the table, but it doesn’t define you. You know, my relationship with you is you your mind, the rest of your looks, your personality, and every other aspect that we all know about in relationships. So, I think the care partner also needs to play a significant role in helping that person, male or female to feel attractive, feel sexual, feel romantic at a time when everything else is going helter skelter with your arms and your legs and your limbs and your speech and everything else and your mood at the same time too. Cause it takes two seconds for that mood to be gone.

Kent Toland:

I think you raised, you know, an important point there. My wife used to describe it as somebody else is in the room, you know, uncle Shakey’s there. Things are awkward. And the more we talk about it, the more we discuss what’s going on, you know, the more it gets worked out and is better.

Arun Mathur:

I think the understanding also Kent is, sometimes for us, at least, is it doesn’t work. You know, it’s just, you can’t get past the dyskinesia and everything. It’s not the end the world. I mean, normally if you’re in an encounter and you’re not having PD in a regular encounter, especially when you’re a younger age of thirties and forties and fifties and things don’t work out, you know, somebody knocks the door or the alarm rings or something, you feel frustrated when you have to walk away, you feel frustrated, that sexual frustration of not having the moment go to fruition. I think it’s important to be understanding from both sides, particularly the care partner, that if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. There’s tomorrow. There’s later today. There’s next week, just walk away from it and say, hey, but if you make a big deal out of it and feel frustrated and show that frustration, then that’s not good for the person with Parkinson’s disease. It’s not good for the care partner.

Kent Toland:

And that’s exactly where we might involve, you know, sex therapists more frequently, you know, people who can understand what’s going on and, you know, provide patients with other alternatives for intimacy. There are many other ways to be intimate than sexual intercourse. And I just think that piece is also important.

Danny Bega:

I just wanna add one perspective that sort of broadens this beyond just the sexual intimacy where I see it every day, it’s usually the care partners that bring it up is just social interactions in general. And I see really frequently this tendency to become more introverted to not want it to, you know, be around friends and do things as often. And some of that is probably stigma about appearance and about you know, not wanting the Parkinson’s to be the focus of a lot of those interactions. And I think some of it is more, is a little bit less tangible and some of it may be chemical changes and changes in sort of sharpness of thinking and other aspects that make people tend to become more introverted. It’s sort of like, there’s this personality that we sometimes see developing and many people with Parkinson’s over time, they just kind of wanna stay.

They don’t wanna be in groups. They don’t want to be, even exercise become something where sometimes people would rather be alone at home doing it than in a group and sort of finding ways to sort of fight against that and help people engage in community, in groups, I think that’s why there’s some success to some of those programs, like the boxing programs that are group boxing activities, where it becomes sort of a support group and an activity where you’re around people who are dealing with similar things. I think that it’s sort of a bigger issue with, some of it is stigma, but I think there’s more to it than that.

Arun Mathur:

Especially early onset, I think Danny, I found that my wife and a lot of the patients that in the first few years, it could be, for one person, it could be six months, for my wife, it was 10 years, 10 years before anyone outside of myself, including our parents knew that she had Parkinson’s. We did everything to hide it. We’d go to events. And she had it mostly in her right hand, the tremor. And so, nobody sees it with anxiety. I would go get the food at the buffet. I’d cut it up for her, the meats, she put her right hand under herself so she could sit on it to stop the tremors, eat with her left hand. And she became very much left hand. We did everything to hide it for the first 10 years. But for that first time, when you’re trying to get your head wrapped around it, you try everything you can to avoid, you change your lifestyle, to avoid people, avoid interaction because of all the stigma associated with it, the feeling of self-worth, feeling of that people are staring at me, is my hand shaking, is my leg shaking. Yeah. It’s huge. A huge issue early on in the disease.

Allan Cole:

And the isolation for me just adds suffering to the suffering if you will. Right. I mean, to whatever extent we’re struggling. It’s for most of us, it’s harder to do when we’re isolated or feeling more alone. So, communication and community are the two themes that I’m sort of grabbing onto you know, being communicative with your partner and your care partners and your significant others, your physician, but also resisting the isolation or the draw toward isolation, particularly as the disease develops. Looking at the clock here, this hour’s going quickly. I wanna make sure we spend a little time on professional issues. Michael, you mentioned that you’re still working and, you know, lots of us who are diagnosed particularly at younger ages, you know, work for a long time after our diagnosis. But again, drawing on my own experience, these conversations come up a lot with people who are still working, how do you sort of help people navigate those questions? This is for really anyone on the panel. How have you yourself navigated those questions? How much longer do you work? How do you assess your capacities for work? You know, what kind of plan should you be formulating? Anything that you might shed light on?

Michael S. Fitts:

So, okay. So let me say this and I’m sure you all will be able to relate to it. So, the nature of my job is I’m an administrator. So, administrators, you know, are in meetings, you know, all day, you have to make decisions and things. So, I’m really wrestling at this point with my executive functioning, because obviously I’ve lost it, things that I used to be able to multitask. I’m just not able to do it anymore. And you know, you want to communicate and you’re trying to communicate with your supervisor and they’re trying to be understanding or whatever, but it kind of comes to a certain point, it’s like, you know, how can you still get the tools and the I guess the treatment that you need in order to do what you need to do.

So, I mean, it goes back to what I was saying about self-worth or whatever, you know, I, as a male am trying to you know, be professional and keep my job and do all that I need to do because it’s something that kind of like somewhat defines me. You know, I hate to say that, but it is. Once you kind of like lose that, my biggest fear as far as like working is concerned or not working, is I’m really afraid that when I stop working, because I’m at the point now I can retire from the institution that I work at. I’m afraid that I’m gonna deteriorate really quickly. So that’s one of the reasons why I try to keep myself as busy as possible. Sometimes I have a tendency to overdo it, but it’s like trying to find that balance, that life balance.

And it’s really frustrating. So, I do have a little bit of advice, and you really have to deal with the situation that you’re dealing with. It depends on, you know, the support system that you have. So, I found out, you know, at first I really tried to hide it. I tried to hide it for a number of years, and I think I was successful in doing it. I had to sit on my hand and do all these little tricks. I had to learn how to, I’m right-handed and that’s my dominant hand. And that’s the hand that has the Parkinson’s in it that I’m having difficulties with. So, trying to, you know, hand write and do that kind of thing, trying to type without having to double type and you have to keep backspace. I mean, it’s a lot for somebody to deal with.

So, I say all that to say this, I do have a great support system here at my job, my work. And we were able to call in a vocational therapist that kind of like is working with me as far as like, you know, possible technology fixes for some of the challenges that I have and just trying to be better focused. So, there are, you know, tools that you have, you know, access to that you might want to try to, but I’m not gonna say it’s easy because, you know, I didn’t tell my employer until it had to have been like two to three years. I didn’t even tell my family you know, for a while, because it was just that it was just that traumatizing for lack of a better term. So once again, communication is key. And I know that’s really a challenge for people, and I know it sounds easier said than done, but really it’s about communication. You just have to kind of like find your way in some manner to kind of like help combat it.

Allan Cole:

Yeah. And the accommodations piece, I don’t wanna lose that, that, you know, there often are accommodations that folks have a legal right to and that, you know, most employers are more than happy to provide, but the communication is really key, Michael. Danny, do you have any thoughts about this with your patients?

Danny Bega:

Yeah. This comes up obviously all the time and particularly with younger people, but definitely make sure you’re using the resources like occupational therapy, social work and a lot of places you can also get assistive technology programs where they can work with you on like talk to text features for your computer and organizing the workspace in a way that suits you. But one thing that I think is really important to think about individually is there’s a point where continuing to work is very beneficial, I think where it keeps you mentally active. It keeps you physically active. It gives you that self-worth that is associated with that job. And again, particularly for younger people with Parkinson’s that can be really important to be able to maintain if you can find ways to maybe stay in the same arena, but potentially take on jobs within that area that are maybe sustainable for longer that are maybe less demanding from a physical or cognitive standpoint over time that may be sustainable for longer.

There’s definitely only a point though, at which people may be pushing themselves to stay in their jobs too long. And you can see the impact. I can see it where they they’re clearly overwhelmed. They’re clearly stressed. They feel like they’re falling behind, they’re getting, they’re having problems and they’re trying to push and push forward and they’re working long hours and so they’re not sleeping well, and they’re not able to take their medications on time, and then it becomes counterproductive. They’re not able to exercise. And so when I start to see that, that to me becomes a concerning piece where really I’m trying to push and encourage people to back away from that work. And then I start to see that they do better when they get disability or retire or whatever that is.

And then lastly, if someone’s job is something that could be potentially dangerous to others. I mean, I’ve had plenty of patients who are, you know, physicians doing surgical fine work. And you know, at first maybe, okay. But you can imagine that over time as the disease starts to impact them more could become dangerous. And so, there are discussions that have to be had around that as well. But yeah, it really is an individual discussion. And, it’s an evolving discussion, depending on kinda how the disease is changing over time also for that individual.

Arun Mathur:

But I think Danny, you have to want to do that. That’s an important piece. So, with firsthand experience with my wife, I had to see her go through her medical practice and little by little, pieces of her practice, first simple thing, she loved babies. She had a huge pediatric practice. And when you have your hand shaking like this, and you’re trying to put an inoculation, a polio shot in, and the mother’s looking at you freaking out, you know, what’s going on with the doctor. That’s tough. And that had to be kind of pulled out of her practice and for anyone else, no big deal, but for a person with Parkinson’s, as far as she was concerned, Parkinson’s won. It won in that moment. And it took a piece of her career out and little by little, she started losing pieces of her career.

So, the only natural recourse, which you and I can logically think, yeah, let’s modify your career, so we get longevity, let’s tailor the career, so it works around your Parkinson’s, so you still have a healthy practice and a different practice, a modified practice, but you get a longer time in your career. That’s a logical approach, but Soania’s approach was, I gotta medicate more. So, she just kept medicating and medicating, going into a spiral. She comes off the meds at five o’clock when she finished her practice, massively dyskinetic, but she got through the day, she pushed through the day. So rather than modify the career, her answer was I’m gonna push through it. Cause if I don’t, Parkinson’s is winning. And I think it’s important for the patients until our neurologist and myself could get through to her in saying, that’s not sustainable long term. You want a long-term career, and she worked for 10 years with Parkinson’s, the only way you’re gonna do that is you have to change your career.

So, it’s still, as you suggested Danny gratifying, but different. And by being different, it doesn’t mean it’s less of a career or you’re less of a person, or you’ve given into the disease. You’re just optimizing yourself, you or I, and any of us, you know, get a sprained ankle, we’re gonna still do what we wanna do with crutches and whatever else we have to, to get through the problem. Albeit that’s a short term, acute situation, not a chronic situation, but that piece that the pa has to be willing to make that change, I think is really important.

Kent Toland:

Yeah. And just to add, that you know, in my position as a surgeon, I, there was no allowance for error or tremor and, you know, I was instantly done. I had fortunately you know, good disability which continues to a point, but I really get back to the point about, you know, reinventing yourself and redefining who you are. And I just think there’s power in that. And I think that’s the main message of Davis Phinney.

Allan Cole:

Yeah. Well said. I know we’re coming up on time. We have just maybe about five minutes left. So just real quickly, what’s one question or topic that we at least should touch, even if for a couple of minutes that we haven’t touched today. Anything that, you know, we wanna mark for a follow up conversation. If Davis Phinney Foundation will have of us back at some point, but what have I not raised, or have we not talked about that’s important to at least name?

Kent Toland:

Well, so the next panelist you should have on in place of me, because you have two qualified physicians is a sex therapist. You know, if this discussion, I think there would be such added benefit for, you know, people who are listening to, you know, how to ask the question, how to get in the door how to, you know, involve their spouse when they, you know, things go unsaid for months and months. And I just think that’s a critical piece.

Arun Mathur:

I agree, especially early on when, when things start getting derailed, it’s harder when you’re, you know, farther down the road of derailed relationship and other you know, psychological psychosocial issues that are, you know, coming into play six months, a year, two years down the road, trying to fix it at that point rather than trying to prevent it early on by making them recognize that this is what’s happening and Kent’s right, I’m a urologist, I’m a plumber, I cut for business. And so, I’m not qualified as a counselor by any stretch of imagination. So having the proper counselors in a panel discussion like this definitely would be helpful. I think for the people.

Danny Bega:

One thing that is wrapped up into all of this for some people is depression. We didn’t really talk about depression. And one of the most common non-motor symptoms we see in at least a third of people with Parkinson’s, but probably more like half of people with Parkinson’s which can lead to issues like intimacy issues and sexual dysfunction and loss of motivation to do things and get out of the house and all of that and how to identify that. And the importance of discussing that I think, it could be talked about for a whole hour session by itself, but it’s really I don’t want to lose that because we didn’t really talk about it.

Allan Cole:

Yeah. Yeah. And I would add anxiety to kind of the other side of depression. It’s almost as common as depression and of course, anxiety, exacerbates symptoms for everyone. So however symptomatic we are, the more anxious we get, typically the more symptomatic we become. So well said, Danny.

Michael S. Fitts:

I wanted to just say one more quick thing too. In addition to the sex therapist, I think that we should be talking about other types of relationships, even single people, people that are dating, because I think a lot of times when we have these discussions and we’re talking about the difficulty, people have a tendency to already have like a caregiver, that kind of thing. And so, I’m on the opposite end of the spectrum. And it’s like, I don’t want anybody, I have this thing about not wanting anybody to have to take care of me because I know it’s, you know, the nature of the disease is degenerative and I just kind of can see it going on and on. And I wouldn’t want to, in my mind, I wouldn’t to hold somebody, to that. I don’t even want them to have to deal with that. It’s hard enough for me to deal with it myself. Let alone try to put that on somebody, you know, a brand new person that I’m trying to date. So.

Allan Cole:

Yeah. Thank you for that, Michael. I think that’s a huge issue. And, I talk to friends about this all the time and we need to, I think just talk more about it and, you know try to remove some of the stigma that sometimes is joined to these kinds of conversations. And really my hope is that, you know, all of us can continue to have these kinds of conversations with one another, with our care partners and our family members, members of our care team, our physicians, and other members of that team. We’re all in this together. We’re all trying to figure it out. Parkinson’s is not a one size fits all. It’s different for all of us. But I’ve learned the hard way that to whatever extent we can you know, come together and lean on each other, we’re gonna have a better shot at sort of thriving with Parkinson’s.

To download the webinar audio, click here.

Show Notes

- Following a Parkinson’s diagnosis, many men’s questions include, “What will I still be able to do, what will I no longer be able to do, and what can I do to slow down the progression?” Panelists also discussed with great candor the issues surrounding sexual performance and identity, care partner concerns, self-esteem, and the challenges of maintaining professional responsibilities while living with a condition that is progressively debilitating.

- Erectile dysfunction (ED) is not uncommon for men living with Parkinson’s, though Parkinson’s may not be the only cause of the condition. Among men living with Parkinson’s, ED has been found to be caused by a combination of factors (of which Parkinson’s is only one): aging, prostate issues, lowered levels of dopamine, etc. The response to ED should involve strategies for all such possible causes.

- Erectile dysfunction is a condition that is difficult to treat for men living with Parkinson’s. Panelists said that simple treatment with Viagra or Cialis is unlikely to be sufficient since those medications might improve performance, but they would not improve intimacy. What’s more important is seeking intimacy during those ON times (hours of the day when Parkinson’s medications are likely to be most effective) like early mornings, after a good night’s sleep (sleep being the time when dopamine restoration is most effective).

- Panelists discussed concerns shared by many men in their desire to slow the progression of Parkinson’s and to identify strategies for maintaining levels of activity and exercise. Exercise and physical activity were commonly cited as the most effective means of combatting the progression of Parkinson’s. Consistent exercise was considered the best way to remain fit, maintain self-esteem, assist in redefining yourself, and realize your own value. Those living with Parkinson’s rarely die of Parkinson’s: the most common causes of death are heart and vascular issues. Exercise is the cure for those and the means to the clarity and optimism that allow you to live well each day.

additional resources

- Learn more about the mood-related symptoms of Parkinson’s in the following webinar recording: Mood and Anxiety in Parkinson’s

- Ready to get involved to increase the research available for men and Parkinson’s? Check out the Michael J Fox Foundation’s available resources to find a study near you

- Be prepared for your visit by completing our downloadable Worksheets, Checklists, and Assessments

- Need to talk to someone who’s been there? Reach out to our Ambassadors!

Explore more

- For additional resources on specific topics like men and Parkinson’s, visit our Topic Pages Hub

about the speakers

Allan Cole, PhD

Allan Cole, PhD

Allan Cole serves as deputy to the president for societal challenges and opportunities at The University of Texas at Austin (UT). He is also a Bert Kruger Smith Centennial Professor in the Steve Hicks School of Social Work and, by courtesy, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Dell Medical School. Cole’s research and teaching interests include chronic illness, health humanities, and mental health. He is the author or editor of 13 books and the author of dozens of chapters, articles, and reviews in volumes and journals related to the fields of social work, counseling, and the psychology of religion. He also serves on the editorial board for the Journal of Spirituality and Religion in Social Work: Social Thought (Taylor & Francis). Professor Cole serves on the Board of Trustees at Headwaters School. He also serves on the Board of Directors at Power for Parkinson’s and moderates PD Wise, an online hub he created for sharing personal stories, experiences, and wisdom gained from living with Parkinson’s that aims to encourage personal connections and opportunities for learning.

Michael S. Fitts

Michael S. Fitts

Michael S. Fitts serves as assistant dean for user access and diversity at The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB Libraries). He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2011 at age 38.

In 2001 he became the first African American faculty member of the Lister Hill Library of the Health Sciences and later went on to become both the first African American assistant director and assistant dean. In 2015, Michael was appointed to the UAB/Lakeshore Research Collaborative — an organization whose primary goal is to promote the health and wellness of people with disabilities.

In addition to his more than 20-year career with UAB, he serves as an advocate for the education of those with early-onset Parkinson’s by being as an example of living successfully and productively with the disease.

Danny Bega, MD, MSCI

Danny Bega, MD, MSCI

Danny Bega is a fellowship trained, board-certified, movement disorders neurologist and Associate Professor of Neurology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He has completed medical school at Rush University and clinical training in neurology at Harvard’s Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham & Women’s Hospital. Dr. Bega has expertise in the care and management of patients with a variety of movement disorders including Parkinson’s disease. He is also the Program Director for the neurology residency at Northwestern. He has completed master’s level training in clinical investigations through the Northwestern Graduate School and is the principal investigator for several industry-sponsored clinical trials. His primary area of interest is the study of complementary and non-pharmacologic interventions in movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and their impact on quality of life, and he has received several grants to carry out this research.

Arun Mather, MD

Arun Mather, MD

A native of Nova Scotia, Dr. Mathur received his Bachelor of Science degree and Doctor of Medicine at Dalhousie University in Halifax. He went on to specialize in urologic surgery at the same institution. He finished his training at the University of Toronto, Sunnybrook Hospital with a fellowship in Urodynamics and female incontinence. A significant part of the training included cancer surgery.

Arun worked for a period of time in Sudbury, Ontario prior to moving to Oshawa in 1997. Since moving to Oshawa he has developed a large general urologic practice with emphasis on laparoscopic surgery, oncology and female incontinence. In 2014 he took on the role of Medical Director of the Surgical Program at Lakeridge Health and in the same year added the role of Adjunct I Associate Professor at Queens University teaching Family Practice residents.

Kent Toland, MD

Kent Toland, MD

Kent is 63 years old and was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in 2013. He completed his residency in Urology at the University of Colorado, following which he enjoyed a 25–year fulfilling career in the field. He currently resides in Portland, Oregon and is married with five children and two grandchildren who live close by. Kent tries to live well every day by staying physically active, skiing, hiking and cycling and is a Team DPF member, having participated in Ride the Rockies in 2019 and 2021.

Live Well Today Webinar Series Presenting Partners*

*While the generous support of our sponsors makes our educational programs available, their donations do not influence Davis Phinney Foundation content, perspective, or speaker selection.