Written by Chris Krueger

As a person living with young onset Parkinson’s (YOPD) who has produced over 150 pieces of educational content for the Davis Phinney Foundation, I feel a lot of responsibility to my fellow people with Parkinson’s.

One responsibility I feel is to always tell the most comprehensive truth about Parkinson’s and how we can live well with it. To do this, I know I must share the best and most complete information about the topics people with Parkinson’s say they want to understand.

Hard Truths and Words with A reason

I know I sometimes fall short of the responsibility I feel to tell the truth about Parkinson’s, but it’s tougher than it sounds. For one thing, experiences of Parkinson’s vary so much. Additionally, there is so much about Parkinson’s that is either not well understood or is just unknown.

Sometimes, it’s also my own fault–like when I fall into convenient shorthand and say something like “Parkinson’s is complicated, complex, or hard.” These words are too small and easy, and every time I use them, they feel wrong. They are insufficient descriptions, but I use them when there isn’t time or space fully explain the whole messy uncertainty of Parkinson’s. It’s the same problem we face when we’re asked how we’re doing. With Parkinson’s, there’s hardly ever enough time to fully address the question.

Since I worry that using these insufficient words might misrepresent what I know and what I have been told by others who have trusted me with their perspectives, in this post, published at the start of Parkinson’s Awareness Month, I want to share 10 things I have in my mind every time I say, “Parkinson’s is complicated, complex, or hard.”

ten THINGS I KNOW ABOUT PARKINSON’s

1.) Parkinson’s Affects Every Sense

When I say, “Parkinson’s is hard,” I am aware that up to 95% of people living with Parkinson’s will experience anosmia, the decreased ability to smell. In fact, loss of olfaction is common in early Parkinson’s and frequently predates motor symptoms. For many of those of us living with Parkinson’s, before we even know we have Parkinson’s, it has already started robbing us of one of our senses.

This is a particularly insidious start. Losing your sense of smell is dangerous: I’ve failed to notice food that was going bad, and I can’t smell the gas if the burner on the stove is left on. It’s socially awkward, too: Have I stepped in something? How’s my breath? Do I need deodorant?

Smell and taste are closely linked, so Parkinson’s commonly impacts two senses before you even know you have it. For me, the impact on my sense of taste has changed the ways I eat. I still reliably taste sweetness, and I am not surprised Parkinson’s is associated with increased sugar intake. Eating more ice cream is one of the more pleasant parts of my life with Parkinson’s, but I know it’s not the healthiest habit, and on days after I eat it, my symptoms tend to be worse.

I also know that over time, Parkinson’s is likely to take some parts of your vision, too, and that it will almost certainly affect the way you process sound. These impacts can leave you mentally fatigued and exhausted both far too often and far too unpredictably.

It’s probably not necessary to describe how Parkinson’s impacts your sense of touch, but with Parkinson’s, even the obvious things are more complicated than they appear. For me, my body is always doing something I didn’t ask it to—my body is always rigid, tremoring, or both—and when someone touches me, it is often startling or even painful. In this way, Parkinson’s can turn affection into just one more thing to manage every moment I’m awake.

2.) Parkinson’s Shortens Lives

When I was diagnosed, I read everything I could get my hands on. Much of what I read said, “You don’t die from Parkinson’s, you die with Parkinson’s.” It didn’t take me long to see that this was ludicrous.

Parkinson’s takes our senses—slowly, perhaps, but it does take them—and it takes our ability to move, to eat, and to use the bathroom on our own. It can involve dementia and psychosis. Of course this affects mortality. How could it not?

I am grateful to the kind and courageous people talking about this. It’s critically important.

3.) anyone can have Parkinson’s

Despite what the most common image of Parkinson’s would have you believe, Parkinson’s is not an old white man’s disease. People of all ages and personal backgrounds live with Parkinson’s. I was 37 when I was diagnosed, and I know people who started having symptoms when they were not even in their teens.

Parkinson’s is a major global health issue, and disparities accessing care from receiving a diagnosis to accessing specialist care or even basic medications contribute to stigma, poor health outcomes, and increases in mortality around the world.

4.) Parkinson’s is unpredictable and Different for Everyone

Part of the challenge of understanding Parkinson’s is that everyone’s experience is different. Partially because of this, I’ve yet to find a movement disorder specialist who is willing to offer me focused insight about what I can expect in the future. This is at least as hard on care partners and families as it is on people with Parkinson’s.

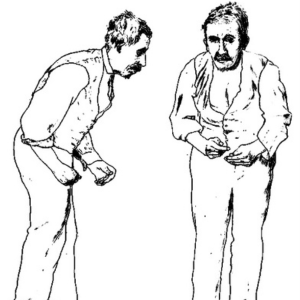

It’s frustrating, even though I know it’s hard to anticipate what changes might come: For the first four years of living with Parkinson’s, I had no tremor at all and bradykinesia was my dominant symptom. But in the past few months, the tremor has been by far my most bothersome symptom.

There are so many ways the variety of Parkinson’s experiences–and how frequently these experiences change–complicates advancing understanding of Parkinson’s.

5.) Parkinson’s is Isolating

This is part of the inherent isolation of Parkinson’s: Those of us who live with it have much in common but also much that is ours alone. Not all our symptoms are shared, and not all are shown–for example, no one can detect internal tremor, and it might be impossible to understand how disconcerting it is unless you have one.

But symptoms are not the only way that Parkinson’s isolates us. I have heard enough stories about lost friendships and divorces to know that Parkinson’s has endless ways to make it harder to stay connected.

At a basic, practical level, Parkinson’s changes what you can do and how long it takes to do it. It changes your ability to be as reliable as you used to be: You can’t know how long it’ll take you to get out of bed, let alone whether you’ll be able to get your feet moving to cross a street. It changes everything from how you care for children to what you can manage to eat. At a deeper level, these changes persistently call into question our sense of who we are and asks us to reevaluate our identity.

6.) Parkinson’s silences those who know the most about it

If all that weren’t enough, I know, too, that one of the most insidious parts of Parkinson’s is the way it affects our ability to communicate. The first time we talked, my friend Heather Kennedy said she thought losing connection to our “Parkinson’s Elders”—those who’ve lived with Parkinson’s longer than we have—was among the most troublesome parts of Parkinson’s. Heather encountered this idea from Gaynor Edwards, founder of Spotlight YOPD.

I believe Heather and Gaynor are right: Communication difficulties don’t just impact the people who experience them and their close friends and families. They hurt everyone in the community. They disconnect those of us newer to Parkinson’s from those whom we have the most to learn.

And it’s not just speech. Parkinson’s makes it harder to text, type, and non-verbally communicate due to facial masking and other mobility limitations.

I am grateful to Heather and to everyone who has shared their insights and experience with me since I was diagnosed. I am so lucky to have gotten to know you all.

7.) limited progress in research is difficult to accept

In light of what Parkinson’s takes from those of us living with it, I know Parkinson’s is hard because—no matter how much amazing work is being done researching and treating it—when we don’t even have an agreed-upon definition of what Parkinson’s is, it sure feels like not enough is being done.

It’s tough, sometimes, knowing that we don’t even really know how Parkinson’s works yet and that research progresses so slowly: There arguably hasn’t been a more important breakthrough than the approval of carbidopa-levodopa, and that happened more than 50 years ago.

8.) Congress should pass the national Plan to end parkinson’s act

It is often difficult to get people to pay attention to Parkinson’s and the challenges of living with it, so it might sound naïve to say this, but it’s hard to understand why the US Congress hasn’t passed the National Plan to End Parkinson’s Act.

I talk about Parkinson’s in public a lot, in part because I want to share that Parkinson’s affects people you might not expect. I have found that almost every person I meet knows someone who has been touched by Parkinson’s. If ending Parkinson’s is not the proper domain of the federal government, I don’t know what is.

Parkinson’s robs people in all parts of the country of each one of their senses, isolates them from their work, their family, and their friends, and shortens their lifespans. It costs the country 52 billion dollars a year.

Passing the National Plan to End Parkinson’s Act will help people everywhere and costs nothing. Our representatives have no reason not to pass this legislation. It should already have been done.

9.) People with Parkinson’s are Resilient, Inspiring, and Strong

At the start of this post, I said it feels wrong when I write “Parkinson’s is hard.”

It feels wrong not just because it is an insufficient description. Calling Parkinson’s hard feels wrong because it makes it sound like Parkinson’s is all negative, but this is not the experience most people seem to have.

Parkinson’s can be both a challenge and a blessing: it presents endless opportunities for growth, which is a truth I’ve heard from people with Parkinson’s around the globe.

I have met more exceptional people because of Parkinson’s than in any other context. I couldn’t possibly list all of them. There are myriad healthcare professionals, researchers, and care partners working to help and bolster understanding. And there are so many people–like my amazing colleagues and the volunteers who support the Davis Phinney Foundation–who dedicate their lives to working in Parkinson’s support organizations. But by far the most exceptional people are those I have met who are living with Parkinson’s. Your resilience abounds!

10.) Tackling The Challenges is worth it: Every Victory Counts

The courage and depth of compassion in this community is astounding, especially given the variety of pain and challenge that Parkinson’s presents. The adversity I see people with Parkinson’s face head on and overcome—some of which I have described above—could so easily crush anyone, but every person I have met with Parkinson’s demonstrates profound fortitude and perseverance. It’s incredibly inspiring.

Parkinson’s can be so humbling at the same time it requires you to keep learning and find new ways to keep going. If you pay attention to the smallest moments—for example, to the minutiae of having your gait become frozen—there are whole universes you can explore. This is a special sort of gift, and it is part of how I explain to myself why so many people with Parkinson’s report experiencing explosions of creativity. We are continually presented with a real and pressing need to find new ways of thinking and clever ways out of the traps Parkinson’s snags us in. These opportunities make us stronger and wiser than we would otherwise have been.

Parkinson’s presents us with truly endless opportunities for reinvention. In the same minute you might face versions of yourself you can barely remember and also new versions of yourself you’ve barely met. Parkinson’s changes, and we change with it, always finding a new way forward. Every time we do this, it’s a victory, and every victory counts.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking a victory requires a fight. Victories don’t only come from battle: With Parkinson’s, most victories are the result of bravely facing a new challenge and triumphantly adapting.

Is all of this hard, complicated, and complex? Of course. But is it worth the effort? When you get to talk with as many people with Parkinson’s as I do, and when you hear so many people say they found something valuable in Parkinson’s—and how many people say that their Parkinson’s diagnosis was when their lives began—there is no other answer but “yes.”

KEEP AN EYE ON THE HORIZON and Live well today

Even though I am wary of saying it, it’s true: Parkinson’s can be unbelievably hard. It challenges your identity over and over again. But as it does this, it also provides a clear direction and a path to explore.

In an early essay, Friedrich Nietzsche presented a general principle: “This is a general law: Every living thing can become healthy, strong, and fruitful only within a horizon; if it is incapable of drawing a horizon around itself or too selfish to restrict its vision to the limits of a horizon drawn by another, it will wither away […]”

This makes sense to me. Everyone needs a context to thrive: A cyclist needs a route like a potter needs a wheel and clay. Even though Parkinson’s certainly limits us, it also provides us with a context and endless opportunities to try new things and find new solutions to the challenges we face because of it.

This makes sense to me. Everyone needs a context to thrive: A cyclist needs a route like a potter needs a wheel and clay. Even though Parkinson’s certainly limits us, it also provides us with a context and endless opportunities to try new things and find new solutions to the challenges we face because of it.

During Parkinson’s Awareness Month, I hope you’ll join me in accepting and perhaps even reveling in this duality of Parkinson’s: It is both unfathomably complicated, complex, and difficult, and at the same time one of the clearest and most persistent invitations imaginable to grow, persevere, and be great.

And keep an eye on the horizon! I believe good things are coming for the Parkinson’s community. We may not always be able to describe all the challenges we face—we may not even always be able to brush our teeth—but we can always count on each other to celebrate even our smallest victories as we continue to find new ways forward.

Thanks for sharing this journey with me.

ADDITIONAL LINKS

Emma Lawton: What Parkinson’s Taught Me

Lori DePorter: Lessons I’ve Learned on my Parkinson’s Journey

Mark Colo: Adaptability Proliferates Possibilities: My Parkinson’s Story

The Parkinson’s Poet: My Sense of Smell