We recently sat down with Mike Studer, PT, DPT, MHS, NCS, CEEAA, CWT, CSST, FAPTA, to talk about neuroplasticity, exercise, sleep, and how important they are to living well with Parkinson’s.

You can watch the full interview now and view the show notes below. Note that Mike is riding his trainer while we talk. He always walks his talk!

Show Notes

- Contrary to popular belief, neuroplasticity is not the growth of new neurons (that’s neurogenesis) but rather the process of learning and connecting neurons that are already there. Otherwise stated, neuroplasticity is the process by which we form new connections in learning.

- Structural neuroplasticity is what our neuronal connections are physically doing: How many of them are there? Are they growing? Are they decreasing? Functional neuroplasticity is how well our neuronal connections are performing.

- Neuroplasticity is important to slow the disease process, preserve what you have, and make connections that you haven’t previously gained because of “learned non-use.” Learned non-use is when you have not built certain neuronal connections because you have rarely done or have stopped doing an activity.

- It is important to see a physical therapist before your Parkinson’s symptoms start to more significantly affect your movement because:

- You are building up a “reserve” or a “redundancy” of neuronal connections and physical fitness so that when symptoms start to increase, they take their toll on your physical well-being less quickly.

- When it comes to exercise, try following the 10/10/10 rule. Ask yourself the following questions when struggling to say yes to exercise:

- How will you feel about not exercising in 10 minutes?

- How will you feel about it in 10 months?

- How will you feel about it in 10 years?

- We have the ability to learn throughout our lifetime.

- When neuroplasticity is increased, you may see the following:

- Faster response and reaction time

- An increase in power (the ability to effect force quickly)

- While it’s important to adapt to continue doing activities you love and are healthy for you as your symptoms progress, it’s equally as important to continue doing as much work yourself as possible. For example, instead of asking your care partner to do everything that is difficult, only ask for their help when you really need it. Much like building muscle, you need to continue to push yourself just beyond your area of comfort to continue building neuroplasticity and slowing the progression of Parkinson’s.

- BDNF is a substrate that helps neurons grow. Everyone has a certain amount of BDNF, but you can increase your BDNF viability through high-intensity exercise.

- High-Intensity exercise should be done at approximately 70-80% of your maximum heart rate.

- High-intensity exercise can be integrated into any of the daily activities you enjoy doing. Work with your physical therapist to figure out how to incorporate high-intensity exercises into activities such as gardening, cooking, playing music, etc.

- When we sleep, our learning becomes solidified in our brain. Sleep also has a role in clearing away accumulations in your brain that build up in degenerative conditions. Finally, growth hormones are released during sleep, which aids in turning physical stimulus on your body (i.e. exercise) into stronger muscles.

remember this

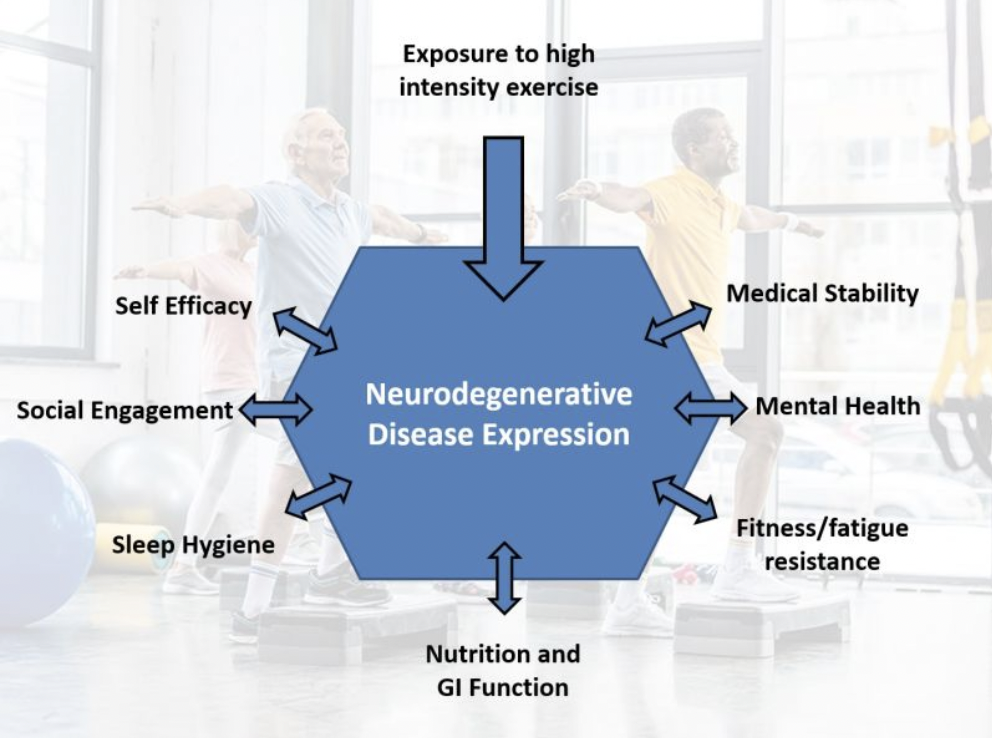

Thank you, Mike Studer, PT, DPT, for this great image. Note the bidirectional arrows in the lower half of the figure. When these are controlled, Parkinson’s expression is reduced. The reverse is also true. When Parkinson’s is more well-controlled, so are these other conditions.

Thank you, Mike Studer, PT, DPT, for this great image. Note the bidirectional arrows in the lower half of the figure. When these are controlled, Parkinson’s expression is reduced. The reverse is also true. When Parkinson’s is more well-controlled, so are these other conditions.

Practices to Implement Starting Today

- The Sit to Stand Challenge – Time yourself for one minute as you go from seated to standing. How many times did you do it? Write it down and do it again every four weeks to track your progress. For entertainment, do it along with us.

- Do some sort of moderate physical activity for 150 minutes per week/21 minutes per day, or 75 minutes if it’s high-intensity exercise, which means just 11 minutes a day.

- You can accumulate 11 minutes of high-intensity exercise throughout the day. You don’t have to do it all at once.

- Choose activities you love doing. If you don’t love it, or at least like it, you won’t do it.

Want to Learn More About Exercise and Parkinson’s?

Significant research studies and anecdotal evidence highlight the critical importance of exercise for people with Parkinson’s. In addition to neuroplasticity, regular physical exercise can improve mobility and coordination, boost your mood, reduce stiffness, and minimize soreness and fatigue. Find out more from this collection of resources. Want more Mike? You can watch his fabulous TEDx talk here.