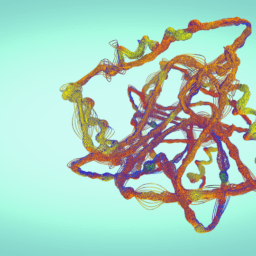

People with Parkinson’s live with a variety of symptoms. One of the most reported is changes to gait or changes to how your body moves while walking. This can include changes like stooped posture, shuffling and shorter footsteps. People can also notice changes in how their arms move while walking—referred to as arm swing. This can include decreased range of motion in swing, slower swing and more asymmetry between how each arm moves while swinging.

Arm and leg movements while walking are “neurally coupled”. That is, the brain network that controls the arms connects to the brain network that controls the legs, and people not living with Parkinson’s swing their arms in concert. Parkinson’s can disrupt these networks and impact how the body moves while walking.

Many questions remain. First, it is not well understood just how these coupled brain networks for movement are related to the networks responsible for cognitive functioning. Next, researchers had questions about gait function when networks for cognitive functioning are used at the same time as walking (known as “dual-task” conditions). Finally, gait changes can be measured by examining leg movements, but these measurements are costly and time intensive. Could there be a more efficient way to measure gait changes while someone is using his or her cognitive networks, too?

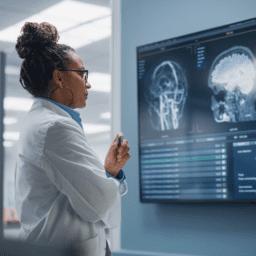

Dr. Baron and colleagues recently studied this in a project funded by the Davis Phinney Foundation. An article published in March 2018 in the journal Parkinson’s and Related Disorders showed that arm movements changed substantially when a person completed a cognitive task that was challenging at the same time when compared to a person who just walked (known as a “single-task” condition).

In this study, twenty-three people with Parkinson’s (ranging from 51-76 years of age with an average time since diagnosis of six years) were assessed an hour after taking antiparkinsonian medication to assess participants during an “on” time.

First, participants completed a series of cognitive tasks while seated to measure performance during a single-task condition. These tasks ranged in levels of difficulty and some examples included recalling a series of numbers said aloud and subtracting seven from a given number and working backward for several minutes.

Next, the participants completed those same cognitive tasks while walking at a comfortable pace on a treadmill (dual-task condition). Dozens of reflective markers placed on participants’ bodies and cameras captured body movements while they walked.

When comparing arm movements between single and dual task conditions, Baron and colleagues found that not only did arm swing length decrease (less swing) but arm movement smoothness also decreased (more jerk). This suggests that gait is affected when a person with Parkinson’s has taxing cognitive demands. The researchers did not observe a difference between the performance on cognitive tasks while participants were seated or walking on a treadmill, suggesting that cognitive function does not suffer as much as motor function when tasks are performed at the same time.

This research is a helpful step towards understanding how the brain of a person with Parkinson’s devotes resources when asked to perform two tasks at one time (e.g., walking and problem-solving). These findings are useful as arm swing change can be an easily evaluated and sensitive measure of gait dysfunction to use during appointments with medical practitioners.

Aside from furthering this understanding of dual-task functioning, using arm swing as a marker of gait dysfunction may be practical in the everyday life of a person with Parkinson’s. Previous research has shown that changes to one’s gait can lead to falling and injury, something many people with Parkinson’s are particularly concerned about. These changes are amplified when the brain must also devote limited resources to a cognitive task. In this sense, it may prove useful to limit cognitive demands until seated thereby reducing your risk of falling.

Want More Practical Articles Like This?

Much more can be found in a powerful new edition of Davis Phinney Foundation’s free Every Victory Counts® manual. It’s jam-packed with up-to-date information about everything Parkinson’s, plus an expanded worksheets and resources section to help you put what you’ve learned into action. Color coding and engaging graphics help guide you through the written material and point you to complementary videos, podcasts and other materials on the Every Victory Counts companion website. And, it is still free of charge thanks to the generosity of our sponsors.

Request your copy of the new Every Victory Counts manual by clicking the button below.