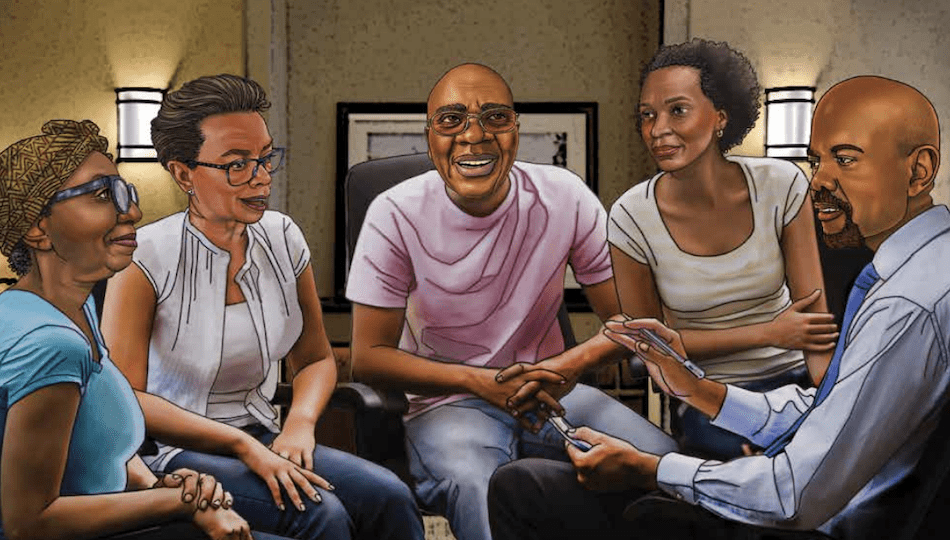

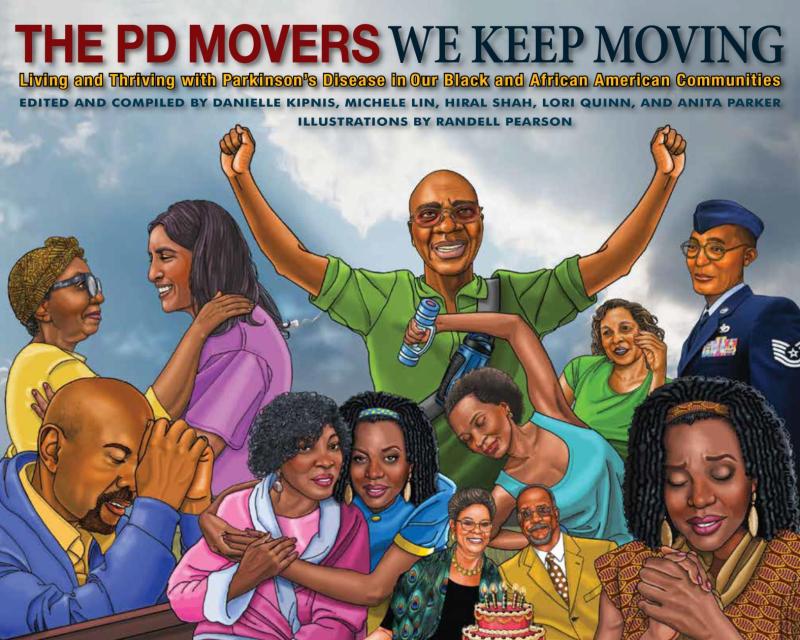

In 2021, PD Movers invited a group of Black and African American individuals with Parkinson’s and their care partners to develop an educational guide for Parkinson’s designed specifically for Black and African American communities. This group of “movers” includes doctors, researchers, and teachers from Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC) and Teachers College, Columbia University. What came from those initial gatherings is a beautiful storybook called PD Movers. It’s filled with narratives of African American and Black individuals, communities, and care partners who are living and thriving with Parkinson’s.

As a way of sharing this work, we hosted three panel-styled webinars and an interview with the illustrator to give you a chance to meet the “movers” of this storybook and advocacy coalition.

We hope after watching this series, you’ll be inspired to initiate the kind of work that would be useful and meaningful to those in your community.

To learn about all of the panelists who were part of the series, visit here.

PD Movers: A Tool for Building Trust, Awareness, and Empowerment in the Black and African American Community

The Power of Story: On Using Narratives in the Black and African American Community to Connect and Inspire Those Affected by Parkinson’s

The Role of Faith-Based Leaders in Health Promotion and Outreach in the Black and African American Community

An Interview with PD Movers Illustrator Randell Pearson

Interested in Becoming an Advocate or Leader in Your Parkinson’s Community?

Learn more about our Ambassador Leadership Program here.

Learn more about becoming a Community Action Committee leader or member through our Healthy Parkinson’s Communities initiative here.