Each month, we spotlight someone in our community who has an inspiring story to tell. Today, we are happy to feature Pete Beidler from Seattle, WA.

What has your journey been like since your Parkinson’s diagnosis?

In 2006, when I was sixty-six, I signed the papers signaling my intention to retire after forty years of teaching English at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. A few weeks later, I noticed a slight tremor in my left hand and forearm. I knew enough to be worried about that tremor because my older sister had had a similar tremor some years before. A doctor eventually told her that she had Parkinson’s. By the time she was diagnosed, her tremor had become more pronounced and she walked slowly and stiffly.

I decided that I would try to get an earlier diagnosis so that, if it was Parkinson’s, I could nip it in the bud. I soon learned that it was, indeed, Parkinson’s but that it was not possible to bud-nip it. Parkinson’s is not a virus that can be headed off with a vaccine, or a cancer that can be cut out, or a diseased kidney that can be replaced. No, Parkinson’s is incurable and progressive. It never gets better. It just hangs around and gets worse.

Not long after, when my wife Anne and I moved to Seattle to be closer to our children and grandchildren, my disease came west right along with me. My new west-coast neurologist told me that my sister and I probably got the disease when we were children growing up in rural Pennsylvania drinking well-water contaminated by nearby farmers who used toxic fertilizers and weed-killing chemicals on their fields. The chemicals did their job for the farmers, then slowly percolated down into the ground-water reservoirs where it did a job on my brain.

“That’s not fair,” I whined. “Why didn’t those farmers get Parkinson’s disease?”

“Maybe they did,” he said. “Or maybe they will, or maybe they have a genetic resistance to Parkinson’s that you and your sister did not have.”

“What’s the prognosis,” I asked him. I loved using big medical words.

“We’ll have to wait and see,” he told me. “Parkinson’s is an imprecise term for a cluster of diseases with varying and shifting symptoms. Some patients are bothered primarily by tremors, others by slowness and stiffness, others by freezing of gait, others by dementia, and so on. There is at present no cure for the disease, but I have good news for you. You have probably had it for years and didn’t even know it. It will probably be many more years before it begins to really hamper your activities. Parkinson’s is slow-moving, and it will not kill you. You’ll die with Parkinson’s, not of it.

A medicine called carbidopa/levodopa (sometimes called L-dopa or Sinemet) will allow you to function pretty normally for many years. There is a new surgical option called deep brain stimulation that has helped some patients. And of course, lots of medical researchers are investigating the disease, so it is only a matter of time until one of them stumbles on a cure. Meanwhile, regular exercise is known to slow down the progression of the disease.”

I obediently became an exercise fanatic. I walked miles and miles and more miles all around Seattle. I bought memberships in gyms, signed up for a dance class, bought a stationary bicycle, joined a rock-steady boxing class, enrolled in a Yoga for People with Parkinson’s class, joined a couple of voice classes for people with Parkinson’s, and signed up for a Pedaling For Parkinson’s tandem-bicycling class.

That was then. This is now, fourteen years later. I am eighty. I took my meds all those years, but they have little effect now. I get little exercise now. Even walking is dangerous. I usually use a cane, a walker, a rollator, or a knee-stroller, but even so, I fall down several times a day. I have banged-up knees, assorted scars and bruises, sore shoulders, two sets of smashed eyeglasses, and two smashed hearing aids. My favorite exercise now is pool.

No, not swimming. Back, in the beginning, I tried swimming as exercise for Parkinson’s in a nearby YMCA pool, but I gave it up almost immediately. I could not swim with my glasses on and my hearing aids in, so I left them in my locker. I squinted my way down the hall to the pool room and carefully stepped into the shallow end. But without my glasses, I could not see who else was in the pool and without my hearing aids, I could not hear if someone spoke to me. Swimming blind and deaf is frightening and lonely.

A few years ago, I discovered the advantages of another kind of pool for Parkinson’s, especially for someone whose most troubling symptom is freezing of gait (FOG).

Can you say more about freezing of gait (FOG)?

The “freezing” has nothing to do with temperature and everything to do with immobility. FOG seems to result from a disconnect between the brain and the feet. My brain tells my feet to step forward, but my feet refuse to move. It is as if they are suddenly glued to the floor. FOG is dangerous.

Most people lean in the direction they want to walk and then pick up the lead-off foot and step it off in the desired direction. Then the other foot comes forward, takes the next step, and off they go. People with FOG, however, lean in the direction they want to go, but sometimes their feet refuse to follow there. The body continues to move in that direction, however, and you tumble forward. Sometimes the feet do take a couple of steps forward and then freeze. The momentum carries the body forward, past the suddenly immobilized feet, and the body tumbles down again. The feet can freeze without warning any time, but most FOG patients learn that their feet are especially subject to freezing as they are approaching an open doorway, an elevator, or the entrance to and the exit from an escalator.

People with FOG fall a lot. They usually fall forward. They learn to fall, if not gracefully, at least more or less safely, but their knees, fingers, wrists, elbows, and shoulders are usually sore, bruised, and scabbed. They learn never to carry things when they try to walk because when they fall their instinct is to use their hands to protect what they are carrying rather than to break their own fall. Such falls are dangerous to the chin, teeth, and nose. There is no good way to prevent FOG. Deep brain stimulation does not help. For people who experience FOG and who want to stay safe, the usual recourse is to yield to the wheelchair. My reluctance to yield to the wheelchair led me to discover pool therapy.

Tell us about pool therapy as exercise for FOGGY patients—that is, patients who have freezing of gait?

My discovery is that playing pool (sometimes called billiards) is a comparatively safe way to have some fun, interact with friends, keep moving, and avoid falls. A few years ago I converted part of my basement here into a pool room. I got a $400 deal on a used but solid pool table and had it set up in my basement. I added a second handrail to the basement stairway so I and my friends could go safely up and down. I’ve had a lot of fun with my toy, but it turns out that pool therapy also has four distinct advantages as exercise therapy for people with FOG.

First, we all know that the small end of a pool cue is the “business end” of the stick, the end that you aim at the white cue-ball to send it careening across the table on its mission to sink one of the colored balls into one of the six pockets. But the big end of the pool cue has a rubber bottom that lets players use the vertically-held cue as a cane. That is a vital function for stumble-prone FOGGY Parkinson’s patients like me. I hold the cue stick in my right hand with the small end up and the wider rubber end down as I move cautiously around the table to get in position for my next shot.

Second, the rim of the table itself doubles as a support for my left hand. I can lean on the table or grab on to the soft rubber bumpers that double as strong finger-grip hand-rails when I move laterally around the table to position myself for my next shot. Once I have shuffled to the place where I will do the actual shooting, I do not need to move my feet anymore. I am safe.

Third, the table itself provides safe support as I do the actual shooting. I just lean forward, position my left hand on the table to provide support for me and the business end of the cue, line up my shot, pull back on the other—that is, the wide—end of the cue, and snap the cue forward to start the white cue ball on its mission. I am safe because I have both feet firmly planted on the floor and my torso is supported by the felt-covered slate base of the table. There is no way I can fall.

And fourth, I can play with friends—male or female—or I can play alone. I can invite a friend over for a game or two of eight-ball, or I can invite a couple of friends over to play a few games of cut-throat. We always have fun ribbing each other about “fluke shots” and “you scratched again” and “how could you miss a can’t-miss shot like that?” If no one is free to play pool with me, I can go down to the basement alone and practice my back-spin or my bank-shots or my ungainly hobbling counter-clockwise around the table with the vertical pool cue in my right hand and the horizontal pool table under my left. It is not vigorous or strenuous exercise, but it keeps me moving and keeps me safe.

Not everyone has room for a pool table in the basement, but many towns have pool halls, and even offer free pool tables one afternoon a week. Of course, many retirement communities have pool tables for the use of residents. There is a song about a stranger who comes to town and tries to convince the townspeople that their town is in Trouble with a capital T and that rhymes with P and that stands for Pool. Well, I am here to tell you that Pool is spelled with a capital P and that rhymes with E and that stands for Exercise.

How do you live well each day?

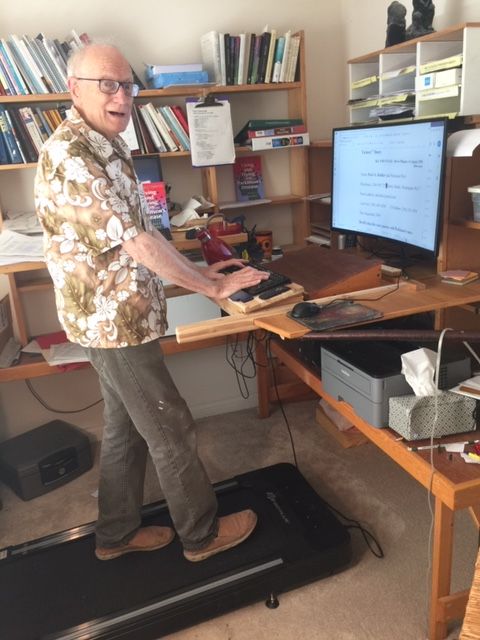

I am not sure that I can really claim to live well every day, but I sure try. I seem to get along best these days if I hold to a flexible routine. I get up around 7 am each day. My first words are almost always to Anne, my wife of fifty-seven years: “Good morning, my darling.” After I dress in the clothes I had laid out the night before, I head to the kitchen table where I swallow my five early-morning pills. I read the morning newspaper as my meds begin to take effect. Around 8 am I eat a bowl of the cereal I had selected the night before. Next, I head upstairs to the stand-up desk in my office where I check my email and work on one writing project or another. I recently bought a small variable-speed treadmill and positioned it in front of my desk so I can get some foot-and-leg exercise when I am working at my computer for long periods of time. For safety, I built in short rails to prevent falls.

I program my cell phone so it buzzes me every two hours as a reminder to take my meds and to move around a little: across the hall to the bathroom, downstairs to my stationary bike, upstairs for my on-line Zoom class on Yoga for People with Parkinson’s, downstairs to my basement workshop or to my pool room, back upstairs to the guest room for a nap, outside to the back porch to read a magazine or work on a picture puzzle, into the television room to catch the news, or to the dining room for the lunch or supper that Anne has lovingly prepared.

After supper, Anne and I eventually migrate to the television room where we hold hands as we watch a Netflix movie or a History Channel program. Then, while Anne takes her shower, I lay out my clothes for the next morning and set out on the kitchen table my packet of pills and a glass of water so I can start the day with my morning meds. I also set out a spoon, a bowl, and a box of cereal. That saves Anne the trouble of making my breakfast. With those preparations, I can dress quickly the next morning and get started on the meds that make it possible for me to move—very cautiously—that morning. Having prepared for the start of the next day, I take my shower and go to bed.

After supper, Anne and I eventually migrate to the television room where we hold hands as we watch a Netflix movie or a History Channel program. Then, while Anne takes her shower, I lay out my clothes for the next morning and set out on the kitchen table my packet of pills and a glass of water so I can start the day with my morning meds. I also set out a spoon, a bowl, and a box of cereal. That saves Anne the trouble of making my breakfast. With those preparations, I can dress quickly the next morning and get started on the meds that make it possible for me to move—very cautiously—that morning. Having prepared for the start of the next day, I take my shower and go to bed.

That is my more-or-less typical day. My favorite days are the untypical days when my friend Griggs Irving stops in for a card game of gin rummy or a pool game of eight-ball; or when my daughter Nora calls to ask if it is a good time for her to drop by with Hugo and Annie for a visit; or when my contractor friend Jamie Paynter texts me to say that he is heading to Home Depot and do I want to ride along?

What do you wish you would have known when you were diagnosed that you know now about living with Parkinson’s?

I wish I had known it was not my fault. I had come to think that rotten health was at least in part punishment for unwise or immoral behavior. If I smoked I would get lung cancer. If I ate too many Snickers bars I would have lots of cavities. If I overate I would get obese and have heart trouble or diabetes. If I drank and drove I would have an accident and lose an arm. If I didn’t use a condom in my condo, I would wind up with a “problem” or a “condition.” What had I done to bring on freezing of gait? Surely, I thought, if I had exercised more or longer or differently, I could have held off the onset of FOG.

I now feel guilty that my Parkinson’s is so hard on my wife. Until two years ago I did most of the driving. Now Anne does all of it. Until six months ago I carried the full trash barrels out every Tuesday morning and carried them back in empty Tuesday afternoon. If I try to do that now, I trip and fall, so Anne has to do it. Almost no one can understand me when I speak now, so Anne has to answer all the phone calls, do all of the runs to the post office and the bank, and has to arrange all of my medical appointments.

And it will get worse: I recently read Jane E. Brody’s article, “The Link between Parkinson’s Disease and Toxic Chemicals,” in the New York Times for July 21, 2020. It troubled me to be reminded that people with Parkinson’s “can live with gradually worsening symptoms for decades, resulting in a huge burden on caregivers. And the economic burden of Parkinson’s is huge.” What right I had to be the cause of such huge human and financial burdens on my wife and family? On one level, I know that it is not really my fault that Anne and our four children will have to suffer even more as my disease progresses, but on another level, I’m not so sure.

Guilt moves in mysterious ways.

You said you spend a lot of time in your office writing. What are you writing about these days?

About Parkinson’s mostly, and about death. Death is supposed to be a scary subject, but I find that in the context of Parkinson’s, it is not so scary. My first Seattle neurologist told me that it was good news that Parkinson’s would not kill me, that I would die with my disease, not of it. At first, I bought into his assumption that longevity was better than brevity. But I have since then wondered why he thought it good news that my disease would not kill me. As I grow older and as my disease progresses, I have begun to question whether it is really preferable for my disease to slowly but inexorably rob me of the ability to live independently, to deprive me of one after the other of my abilities to walk, work, build, speak, write, move, take care of others, take care of myself? He seemed to assume that a long, miserable, dysfunctional life was better than a short, happy, functional life.

He wanted me never to give up hope that scientists would discover a cure. Surely he knew then what I have since figured out: that even if a “cure” is soon found and fast-tracked through the FDA approval process, it will not bring those dead cells in my brain back to life.

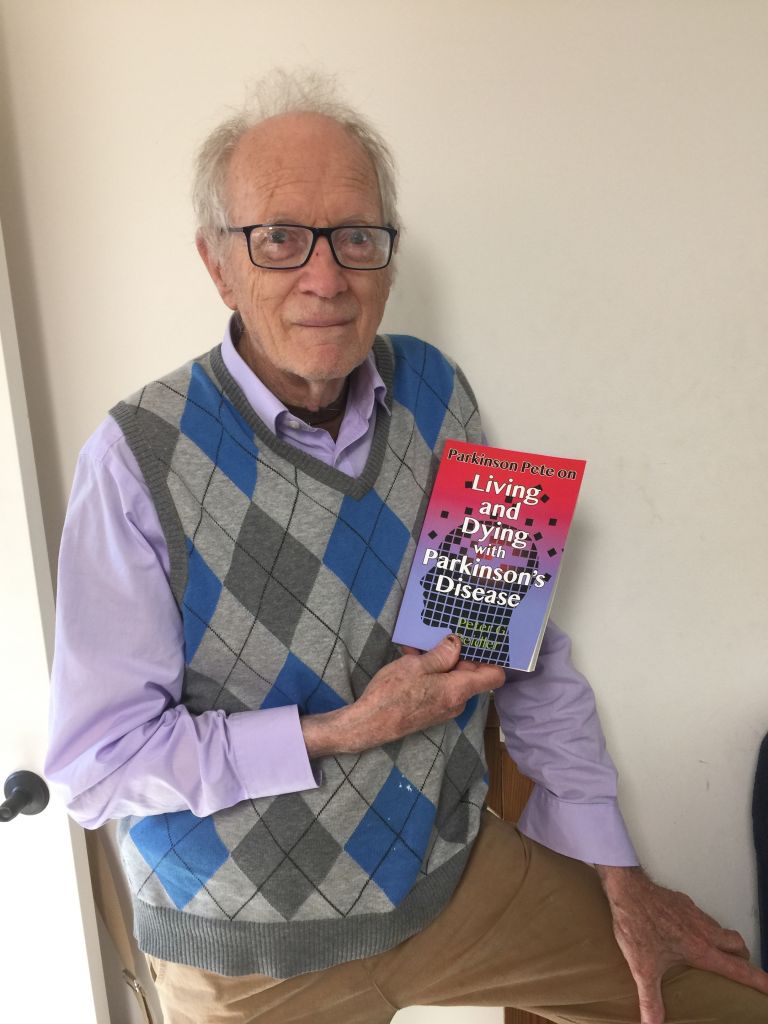

I decided to purchase, read, and write reviews of lots of books about Parkinson’s. I gathered the reviews together and published them in 2018 under the title Parkinson Pete’s Bookshelves: Reviews of Eighty-Nine Books about Parkinson’s Disease. Most of the books dealt with the easy, early stages of the disease and ended with the vague hope that the cure would soon be found. None had much to say about how Parkinson’s patients and their families should react to the helpless immobility of the later stages. I decided to write the book that no one else would write.

My second book about Parkinson’s was published in the late spring of 2020, just about the time that the coronavirus was turning the world’s population into masked and socially distanced Lone Rangers. It might interest readers of this essay to know that Polly Dawkins, executive director of the Davis Phinney Foundation, kindly offered to write a review of my book. In her review, she said: “I was immediately drawn in by Parkinson Pete on Living and Dying with Parkinson’s Disease. Pete writes honestly about his experiences living with Parkinson’s. This compelling book creates a sense of urgency for people affected by Parkinson’s by showing that there is much they can do to improve their lives if they take charge. His book aligns closely with the work of the Davis Phinney Foundation whose mission is to help people with Parkinson’s live well today. Our years of work in this community have shown that those who are happiest and have the best outcomes are those who have followed Pete’s cogent advice.”

To order Parkinson Pete on Living and Dying with Parkinson’s Disease, ask your local bookstore to order you a copy, or order one directly from Amazon.com in either a Kindle ($9.95) or a print ($15.95) edition.

To order Parkinson Pete on Living and Dying with Parkinson’s Disease, ask your local bookstore to order you a copy, or order one directly from Amazon.com in either a Kindle ($9.95) or a print ($15.95) edition.

PETE BEIDLER’S PHILOSOPHY

What do you wish everyone living with Parkinson’s knew about living well?

Remember to be the kind of person YOU like to be around: cheerful not morose, self-reliant not demanding, singing not whining, laughing not complaining. Be grateful that Parkinson’s gives you a good long time to get your affairs and your thinking in order, to prepare yourself and your family for what lies ahead. You will discover that you have more choices than you probably think you have about how to live well and die responsibly. Ask yourself the tough questions: Is it really so bad to have this disease? Do you really want to live as long as possible? Do you really want to saddle your favorite people with the care, feeding, cleaning, and expense of the inert person you may become? What alternatives do you have? Communicate your thoughts about end-of-life decisions to your doctor and your family. Do not allow the lack of a perfect life or a perfect death to distract you from appreciating the fact that you have had a good life and can lay plans for a good death.

Remember that to live well is also to die well. It is impossible for you to live well if you are fearful and resentful about your long-drawn-out disease. To live well is to take charge of your life, yes, but also accept the inevitability and universality of dying. It is to welcome the future with a brave smile of relief and joy and to step out cheerfully to greet it with a proud sense of victory.

Remember that to live well is also to die well. It is impossible for you to live well if you are fearful and resentful about your long-drawn-out disease. To live well is to take charge of your life, yes, but also accept the inevitability and universality of dying. It is to welcome the future with a brave smile of relief and joy and to step out cheerfully to greet it with a proud sense of victory.

SHARE YOUR VICTORY

Each month, we spotlight people from our Parkinson’s community who embody living well today – what we call Moments of Victory®

Your story, like Pete’s, could be featured on our blog and Facebook page so others can learn from your experiences and victories.